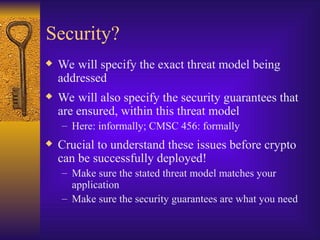

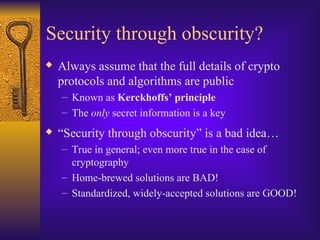

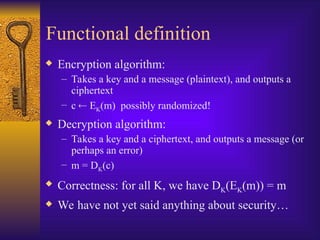

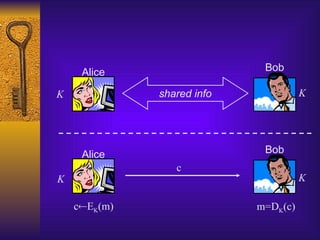

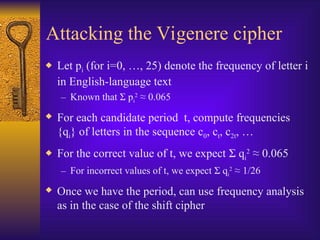

The document discusses the goals and methods of cryptography, outlining key concepts such as confidentiality, integrity, and authentication. It emphasizes the importance of established cryptographic standards over homemade solutions and introduces various encryption algorithms, including classical examples like the shift and Vigenère ciphers. Additionally, it highlights the need for formal definitions of security and understanding threat models to ensure effective cryptographic implementations.

![Defining secrecy (take 1)

Even an adversary running for an unbounded

amount of time learns nothing about the message

from the ciphertext

Perfect secrecy

Formally, for all distributions over the message

space, all m, and all c:

Pr[M=m | C=c] = Pr[M=m]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture2-cryptographyitsusesandlimitations-250116075623-dacb9894/85/lecture2-Cryptography-Its-Uses-and-Limitations-ppt-29-320.jpg)