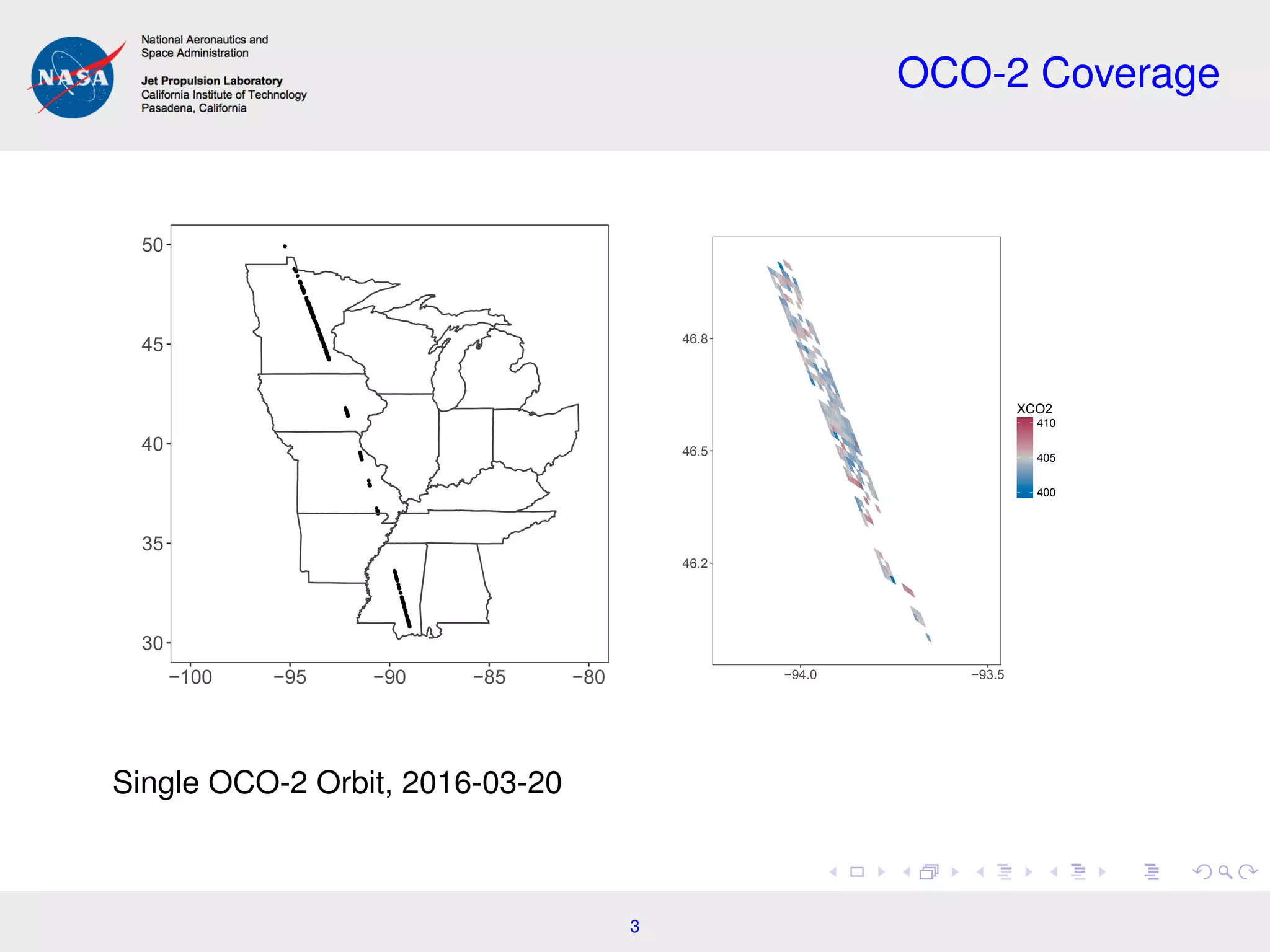

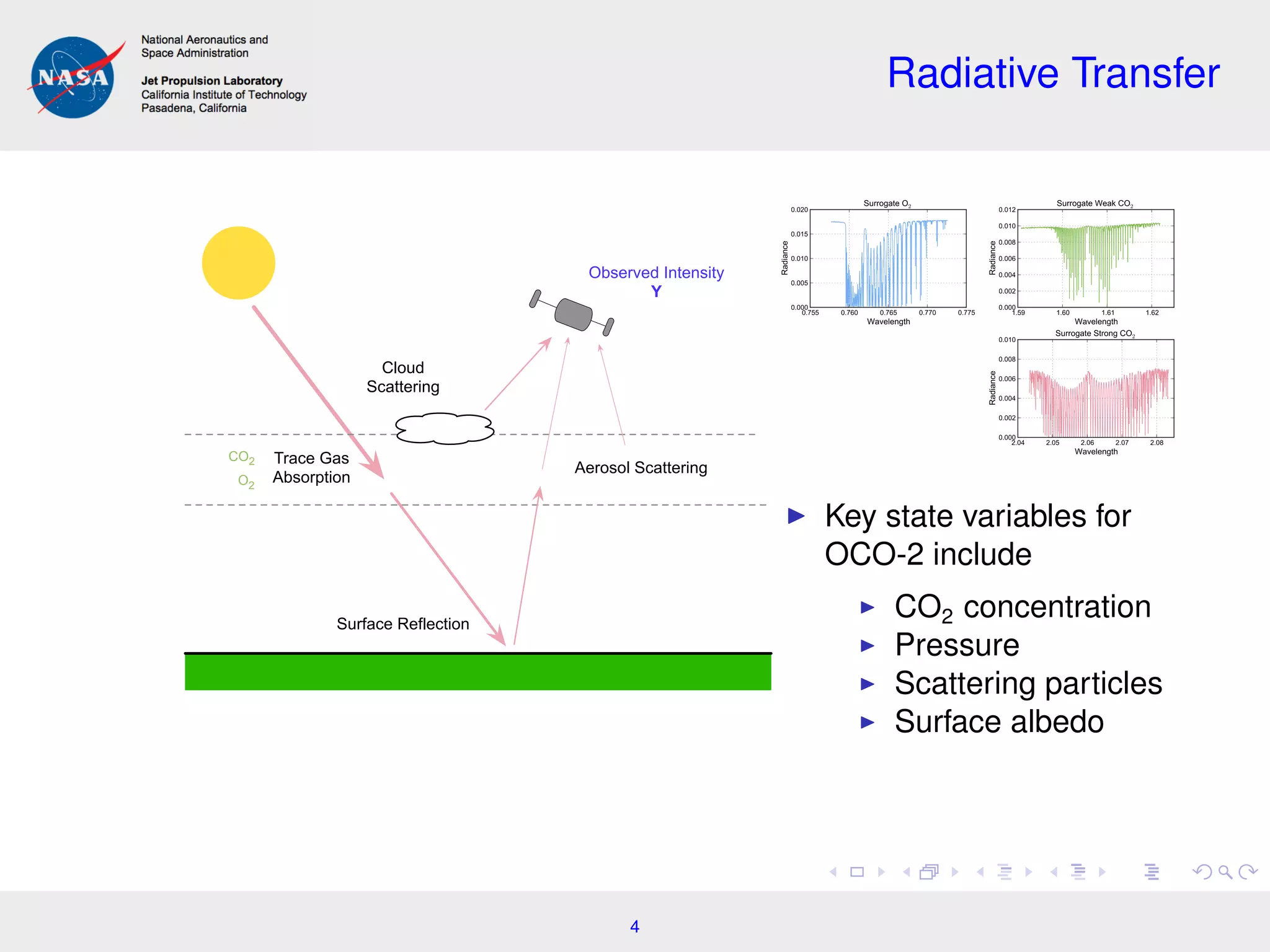

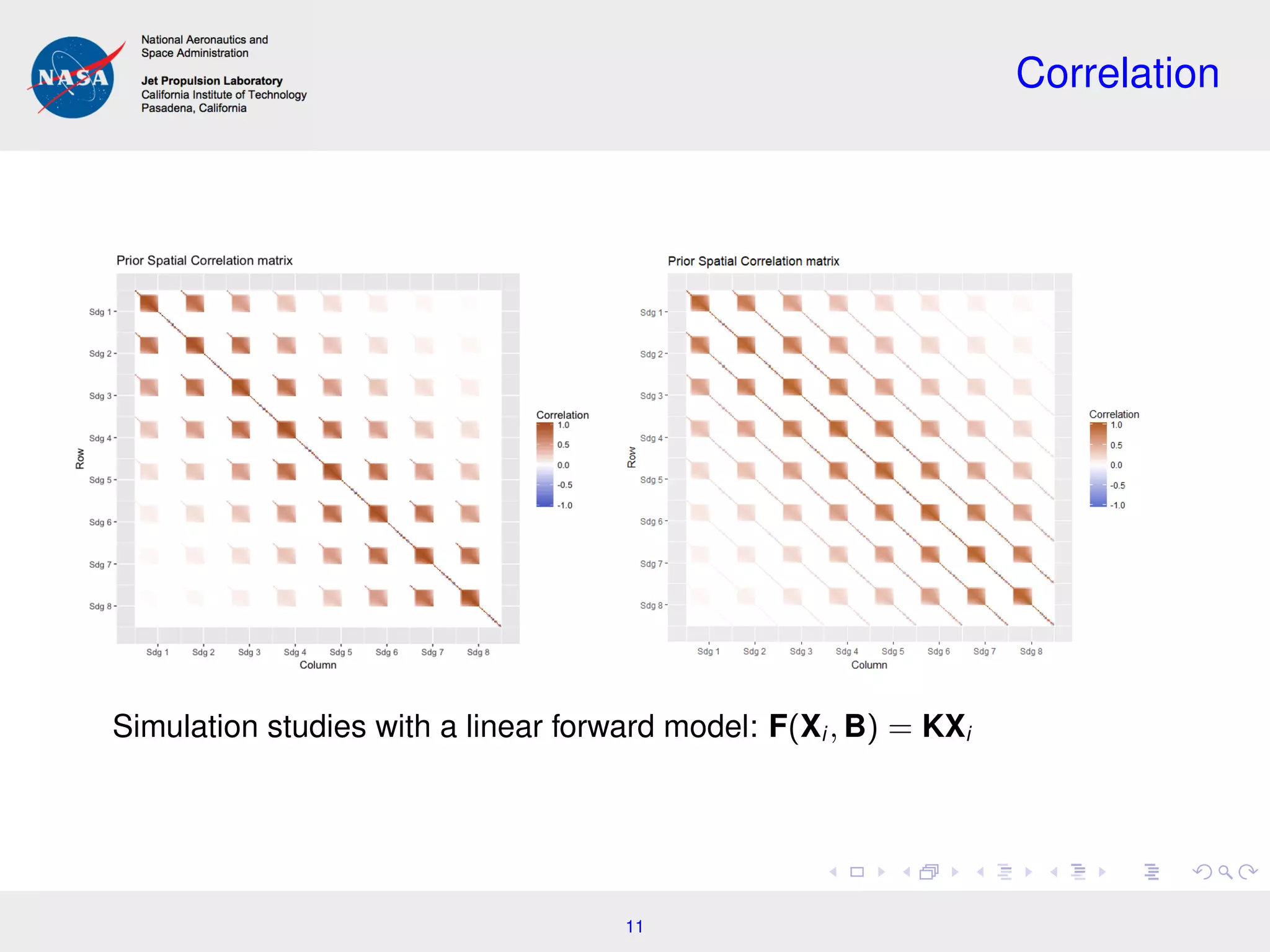

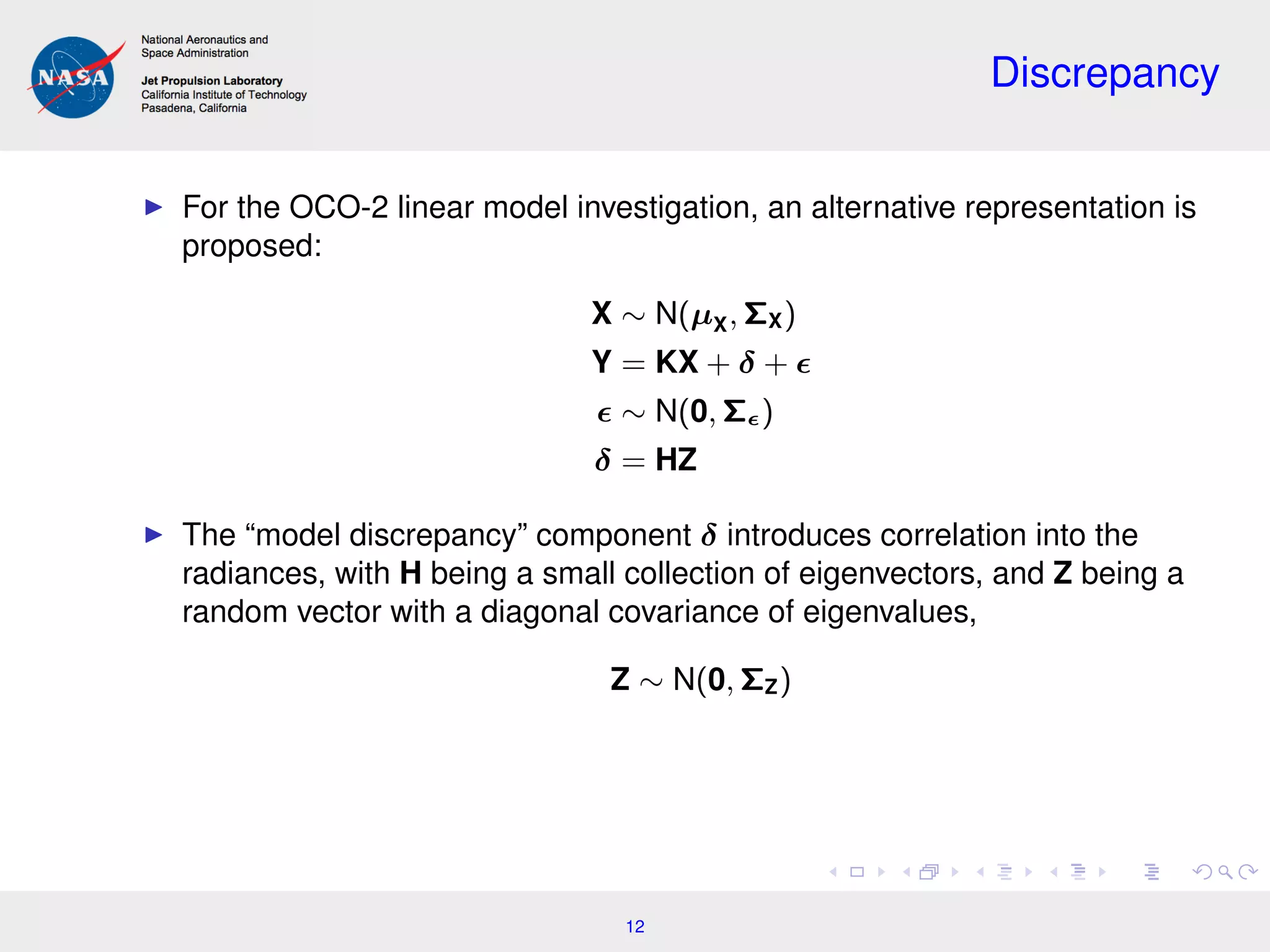

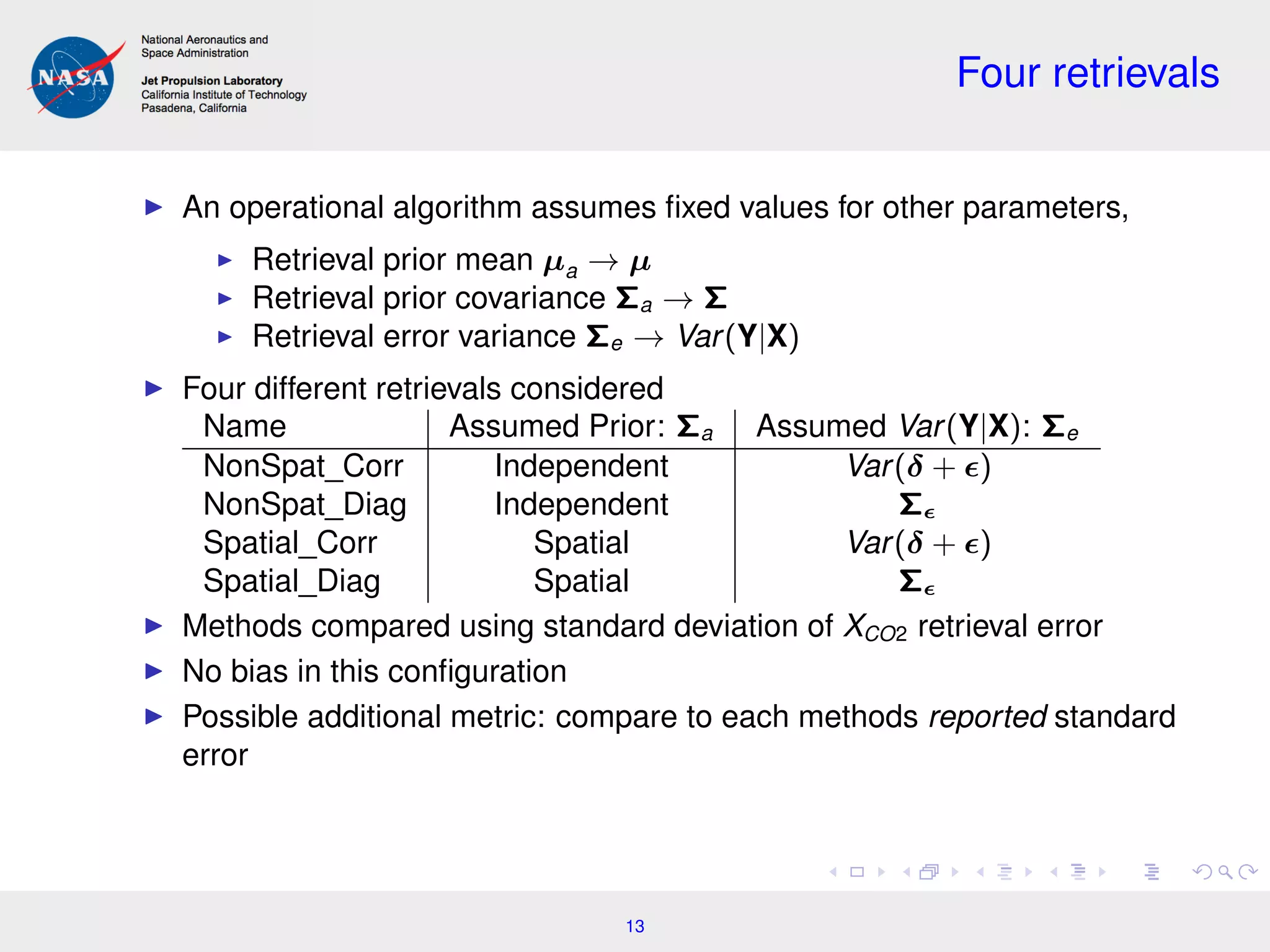

The document discusses incorporating spatial dependence into remote sensing inverse problems, particularly using data from NASA's OCO-2 satellite to improve estimates of atmospheric CO2. It outlines the statistical modeling and hierarchical approaches used to link measurement data to state vectors, highlighting the impact of spatial correlations on retrieval errors. Future work aims to refine these methods for larger spatial domains and enhance the realism of spatial process characterizations.

![Statistical Model

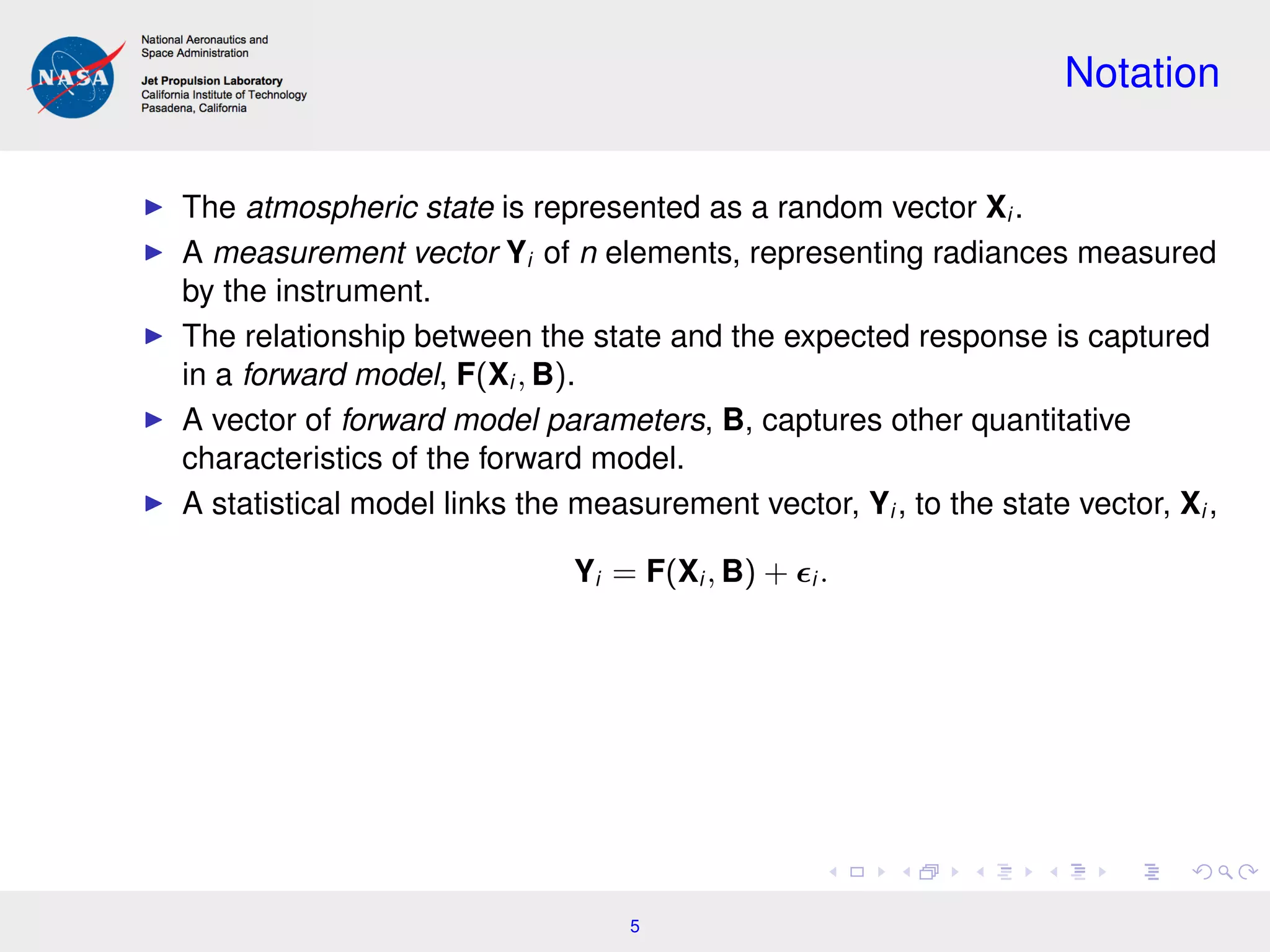

Consider a hierarchical model for a single pixel/footprint,

Xi ∼ MVN (µi , Σi )

Yi |Xi , B ∼ MVN (F(Xi , B), Σ )

Σ = Var ( i )

The conditional distribution can be used for inference on the state,

−2 ln[Xi |Yi , B] = (Yi − F(Xi , B))T

Σ−1

(Yi − F(Xi , B))

+ (Xi − µi )T

Σ−1

i (Xi − µi ) + constant.

6](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/hobbssamsitransition20180514-180515124846/75/CLIM-Transition-Workshop-Incorporating-Spatial-Dependence-in-Remote-Sensing-Inverse-Problems-Jon-Hobbs-May-14-2018-6-2048.jpg)

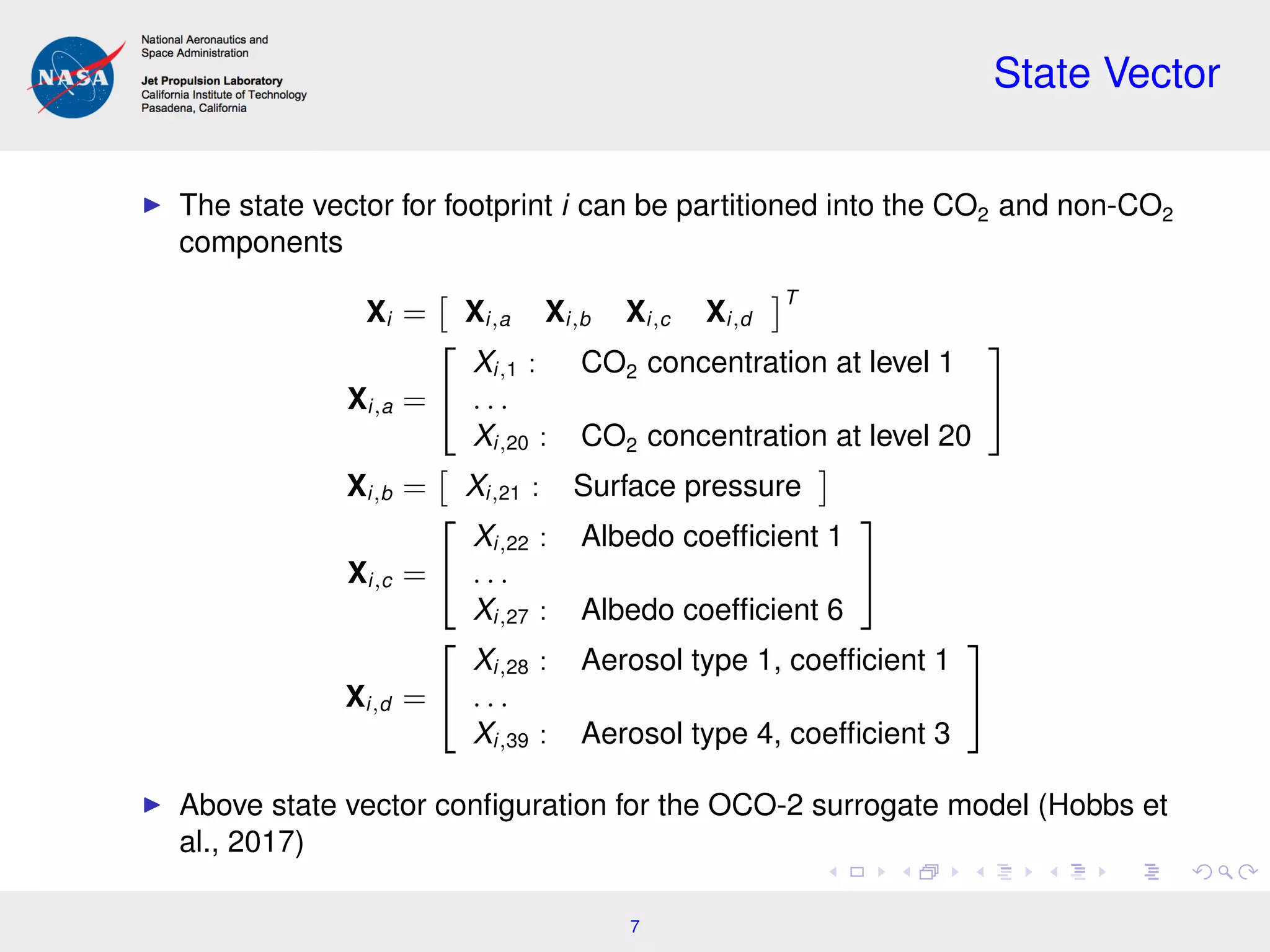

![Spatial Case

Consider, X = [X1 X2 . . . X8] , a collection of state vectors along an

eight-footprint transect:

X1 X2 X3 X4 X5 X6 X7 X8

Joint distribution

X ∼ MVN(µ, Σ)

Cost function

−2 ln[X|Y, B] =

8

i=1

(Yi − F(Xi , B))T

Σ−1

(Yi − F(Xi , B))

+ (X − µ)T

Σ−1

(X − µ) + constant.

Example of a multi-pixel retrieval (Dubovik et al., 2011)

9](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/hobbssamsitransition20180514-180515124846/75/CLIM-Transition-Workshop-Incorporating-Spatial-Dependence-in-Remote-Sensing-Inverse-Problems-Jon-Hobbs-May-14-2018-9-2048.jpg)

![Retrieval Error

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

0.5

0.6

0.7

0.8

FP1 FP2 FP3 FP4 FP5 FP6 FP7 FP8

Footprint

ErrorStdDev[ppm]

Model

q

q

q

q

NonSpat_Corr

NonSpat_Diag

Spatial_Corr

Spatial_Diag

Retrieval Error Variability

14](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/hobbssamsitransition20180514-180515124846/75/CLIM-Transition-Workshop-Incorporating-Spatial-Dependence-in-Remote-Sensing-Inverse-Problems-Jon-Hobbs-May-14-2018-14-2048.jpg)

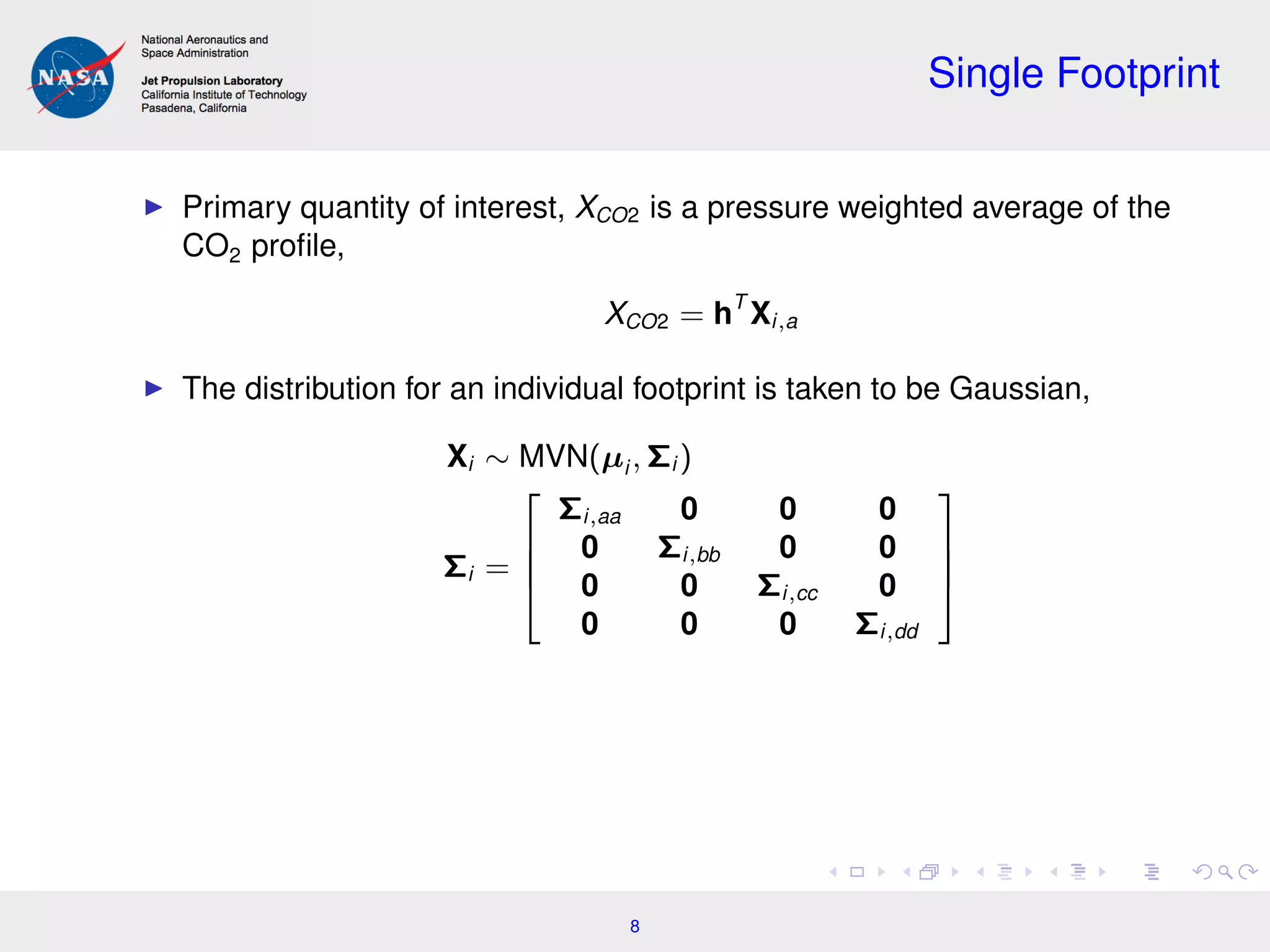

![Retrieval Error

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

0.8

1.0

1.2

1.4

FP1 FP2 FP3 FP4 FP5 FP6 FP7 FP8

Footprint

ErrorStdDev[ppm]

Model

q

q

q

q

NonSpat_Corr

NonSpat_Diag

Spatial_Corr

Spatial_Diag

Retrieval Error Variability

Operational Prior

16](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/hobbssamsitransition20180514-180515124846/75/CLIM-Transition-Workshop-Incorporating-Spatial-Dependence-in-Remote-Sensing-Inverse-Problems-Jon-Hobbs-May-14-2018-16-2048.jpg)

![Templates

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

0.0

0.5

1.0

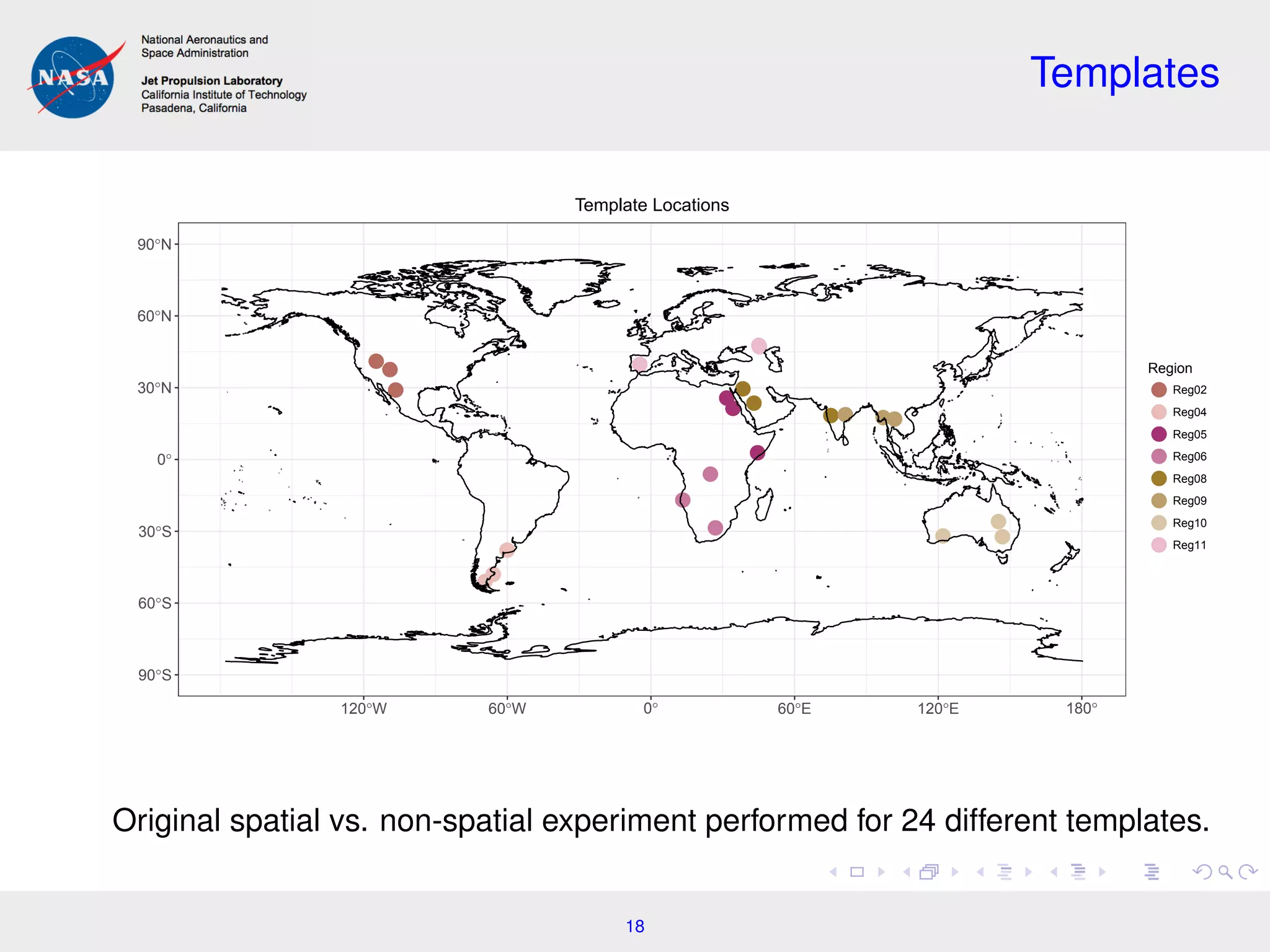

02 04 05 06 08 09 10 11

Region

ErrorStdDev[ppm]

Model

q NonSpatial

Spatial

Region Errors

Retrieval error standard deviation for Footprint 4.

19](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/hobbssamsitransition20180514-180515124846/75/CLIM-Transition-Workshop-Incorporating-Spatial-Dependence-in-Remote-Sensing-Inverse-Problems-Jon-Hobbs-May-14-2018-19-2048.jpg)