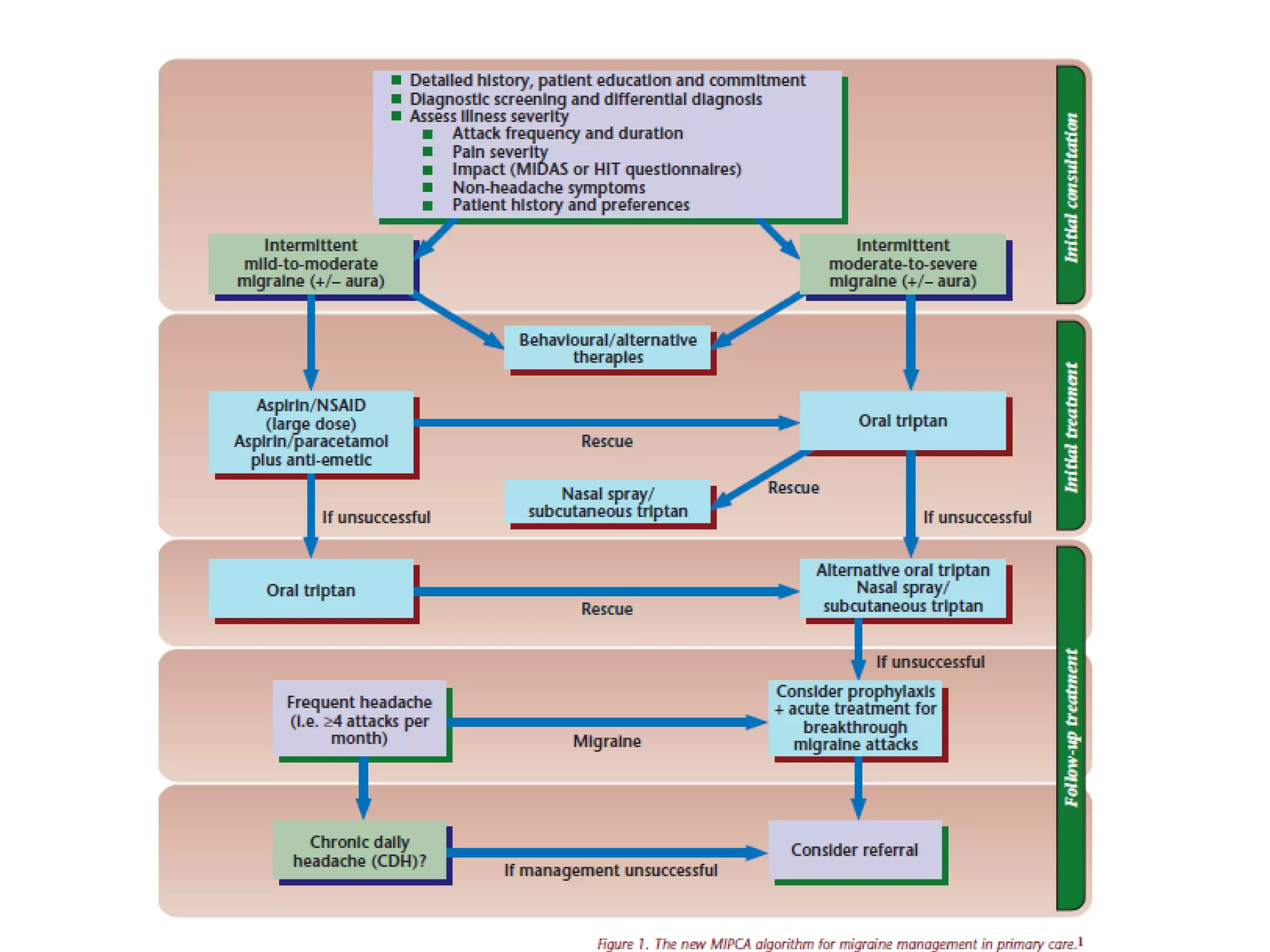

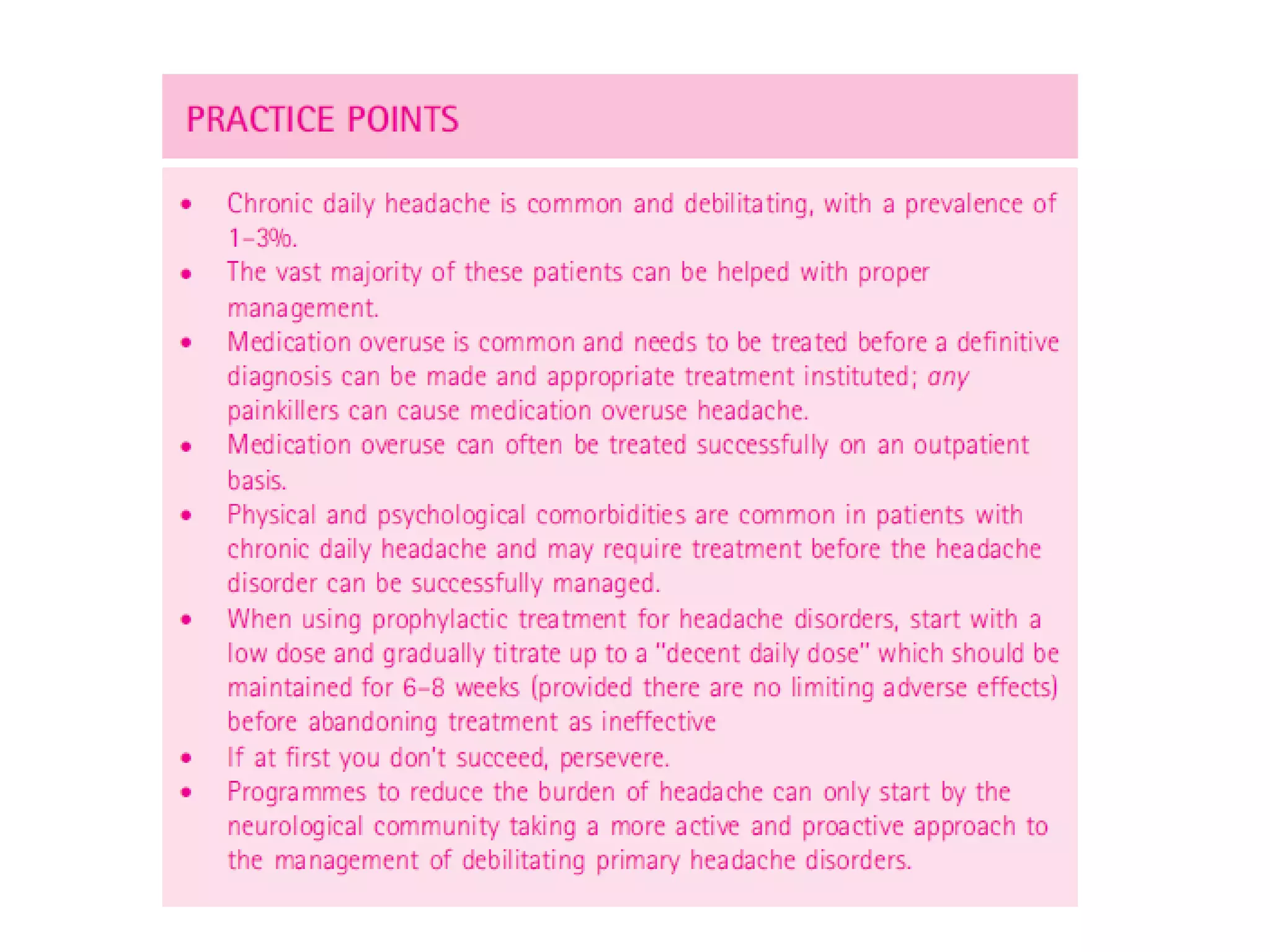

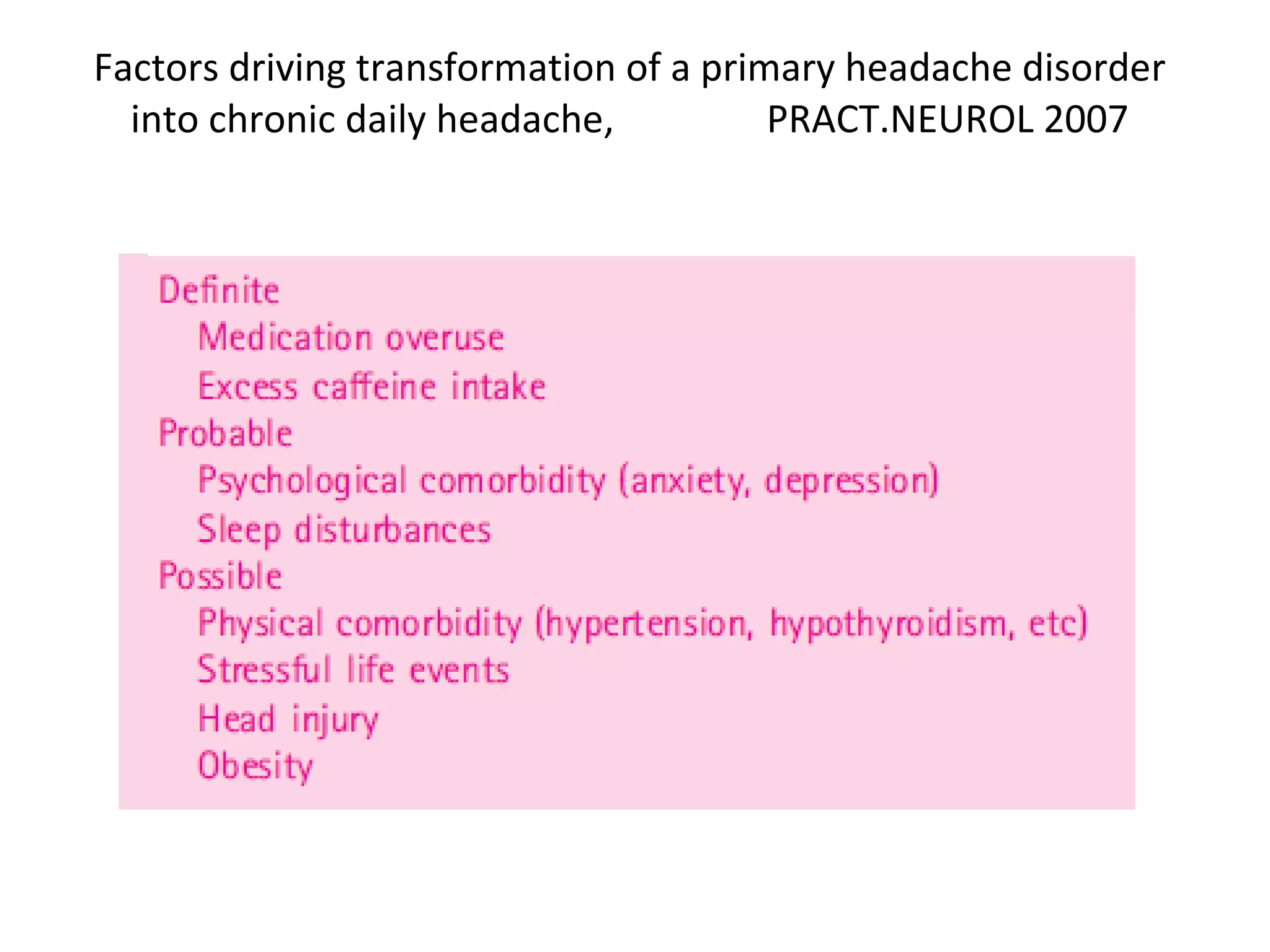

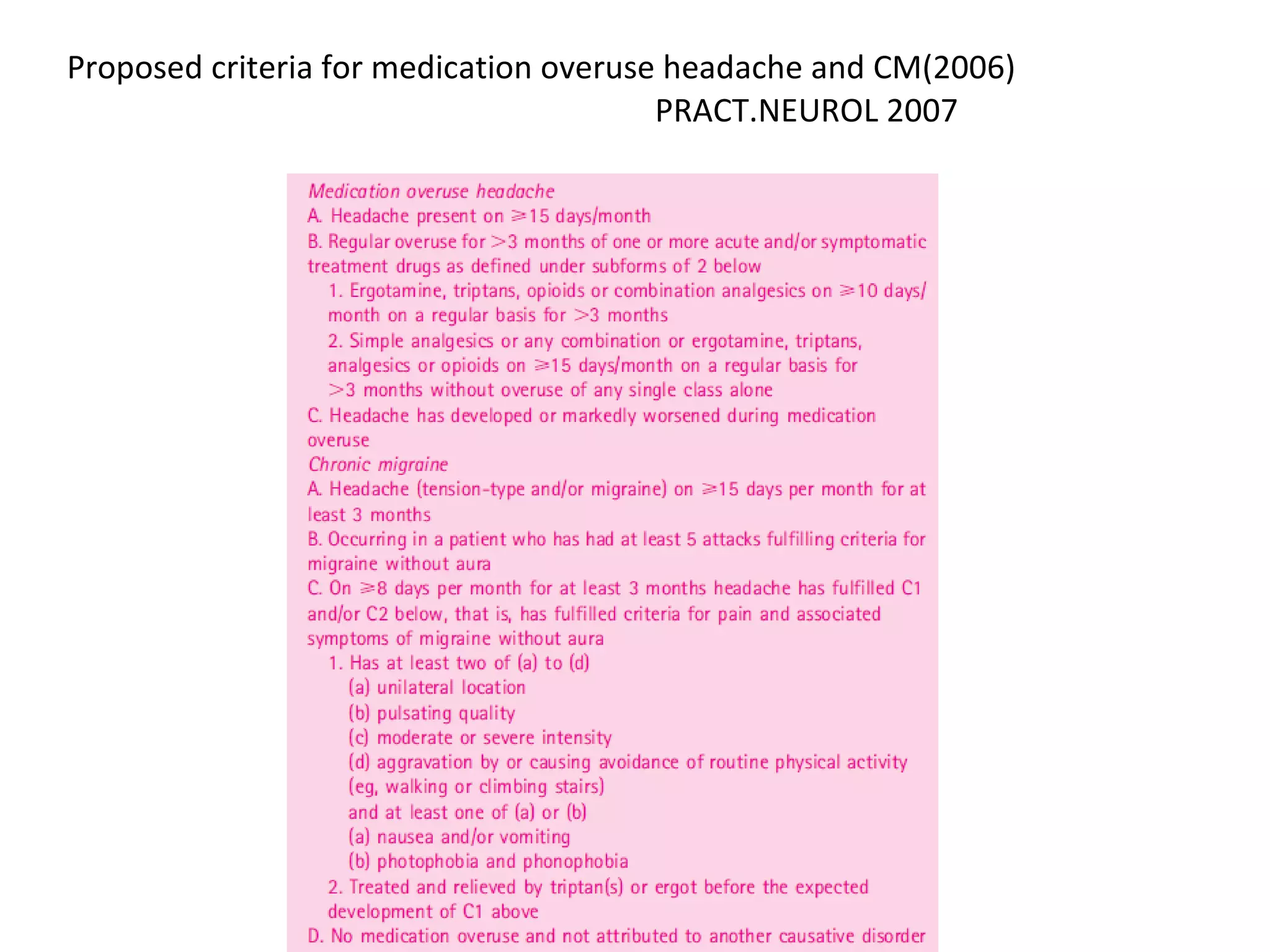

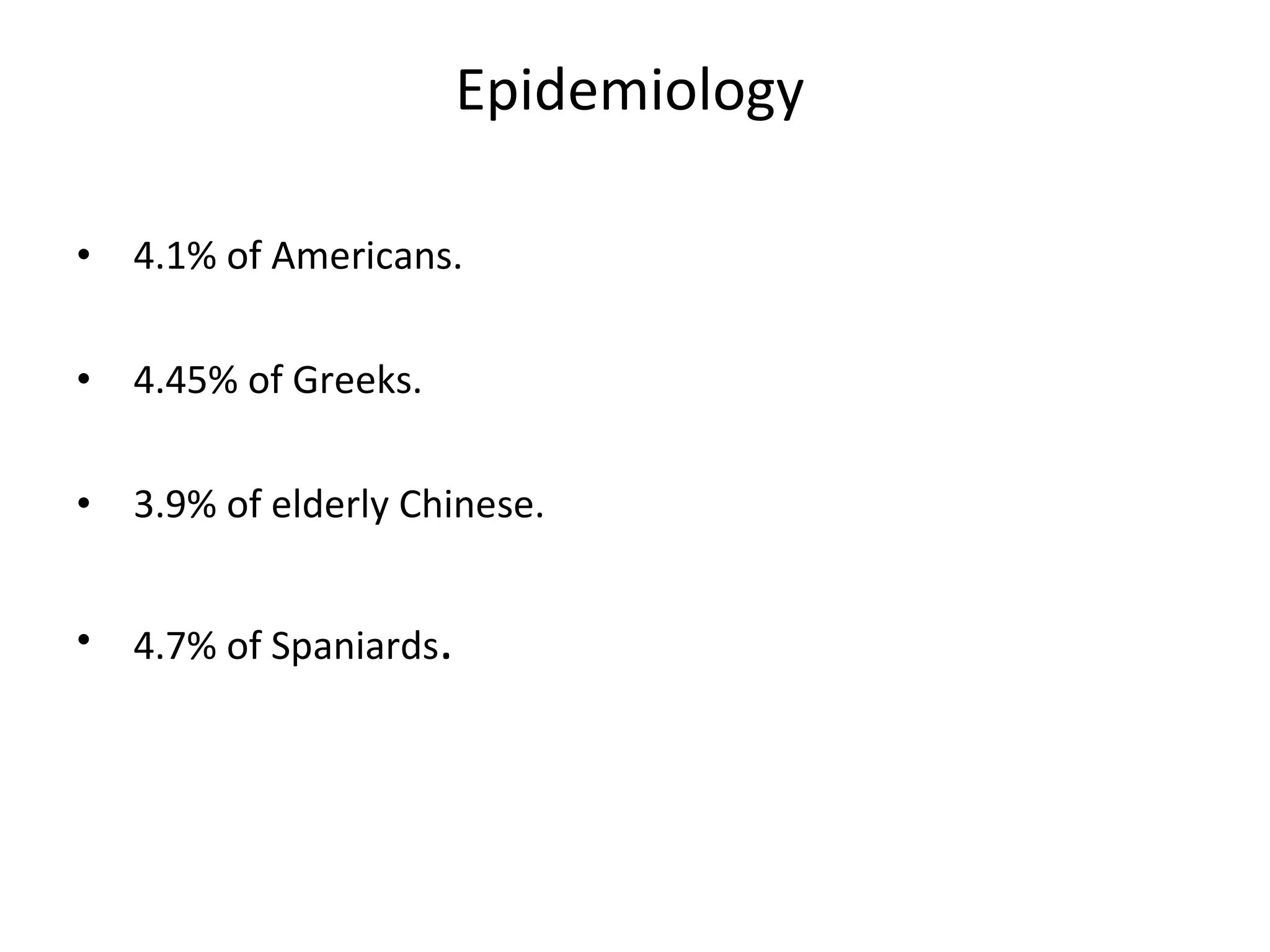

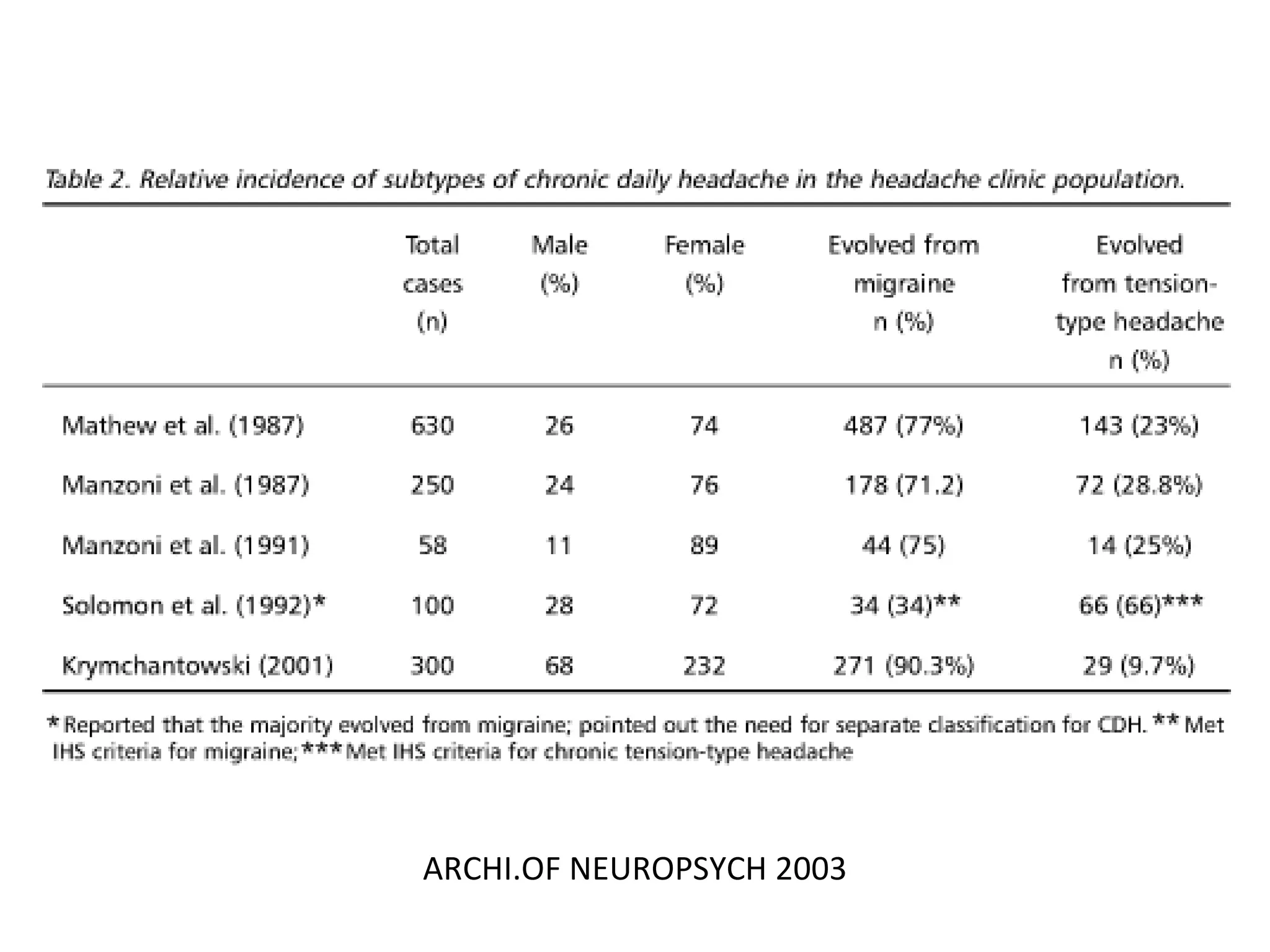

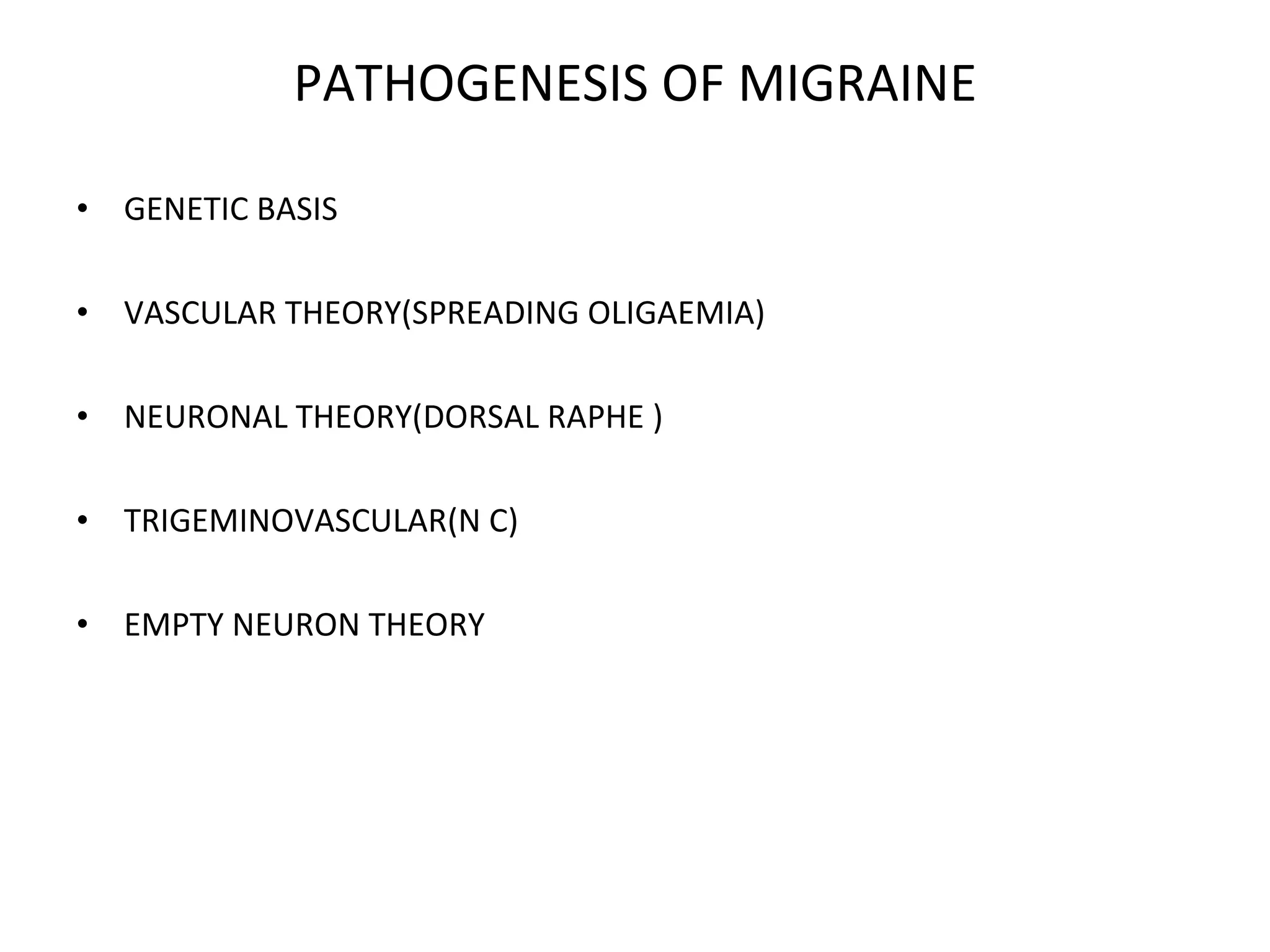

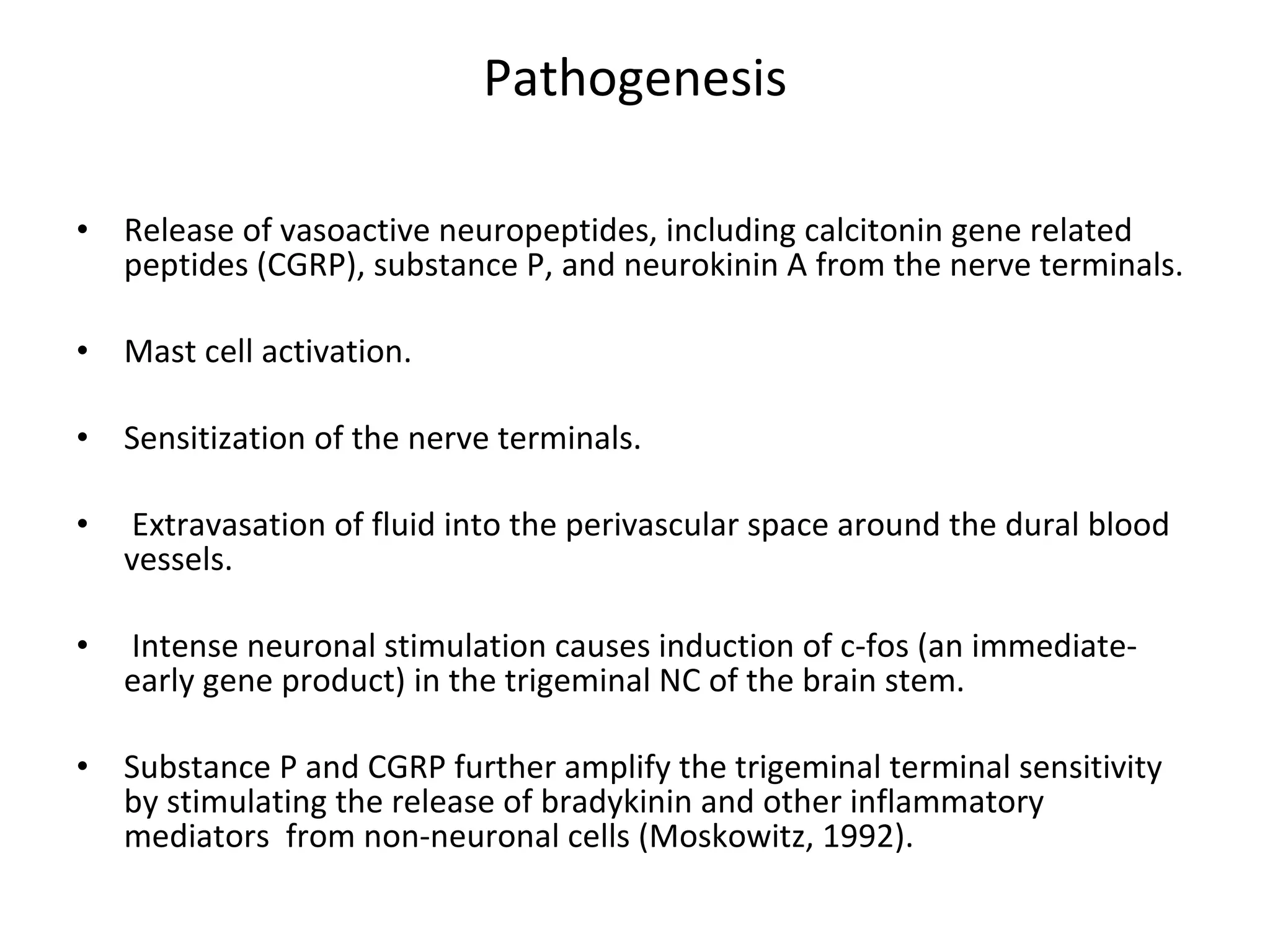

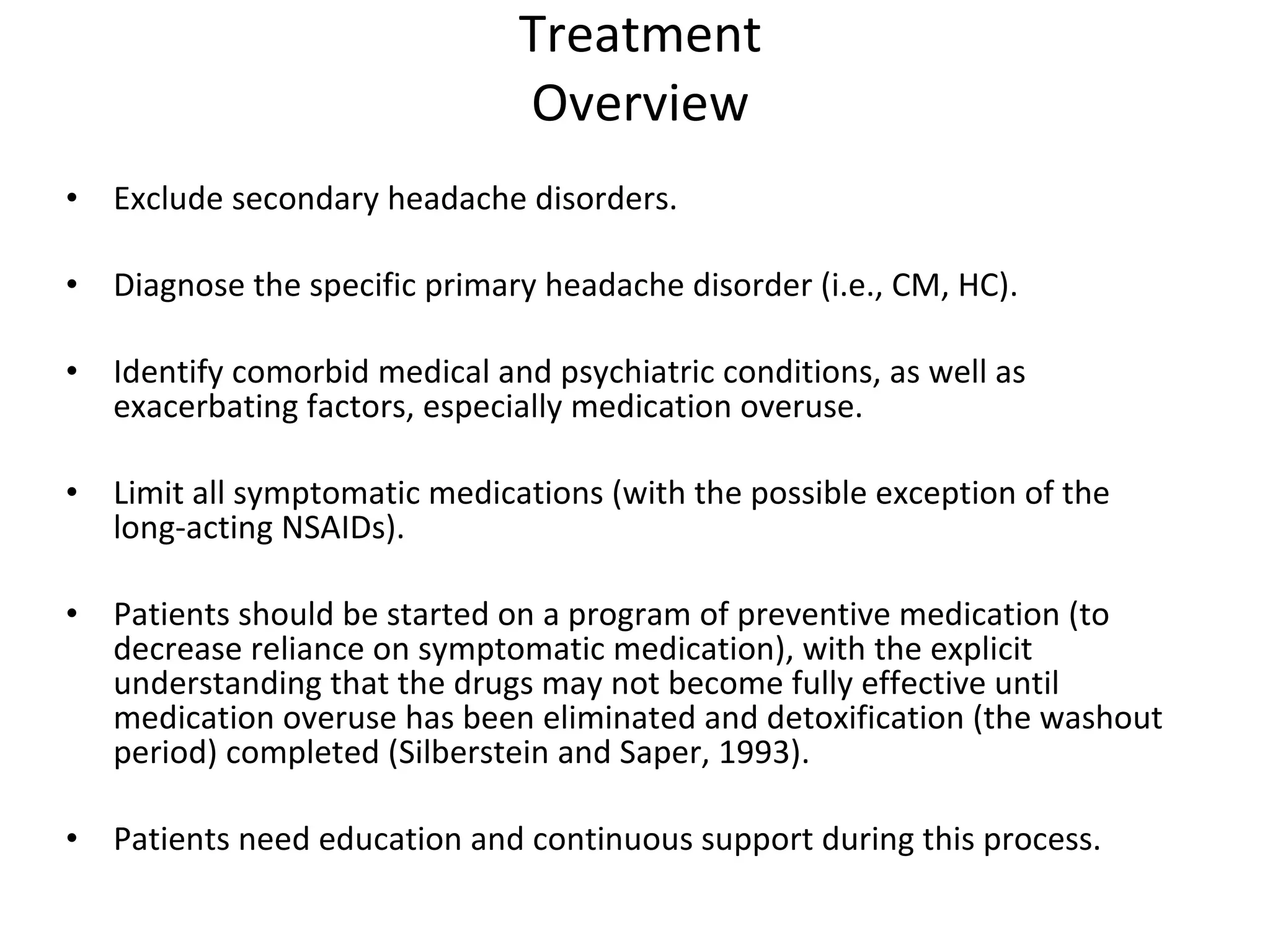

This document discusses chronic daily headache (CDH), defined as a headache occurring on 15 or more days per month for more than 3 months. It describes the classification of primary and secondary CDH according to the International Headache Society. Primary CDH includes chronic migraine, chronic tension-type headache, new daily persistent headache, and hemicrania continua. Secondary CDH is caused by underlying head/neck issues, vascular disorders, infections, or psychiatric disorders. Risk factors, pathophysiology, treatment approaches including medication overuse management, and lifestyle modifications are summarized.

![Chronic daily headache Primary chronic daily headache Headache duration >4 hours Chronic migraine (previously transformed migraine) Chronic tension-type headache New daily persistent headache Hemicrania continua Headache duration <4 hours Cluster headache Paroxysmal hemicranias Hypnic headache Idiopathic stabbing headache Secondary chronic daily headache Post-traumatic headache Cervical spine disorders Headache associated with vascular disorders (arteriovenous malformation; arteritis, including giant cell arteritis; dissection; and subdural hematoma) Headache associated with nonvascular intracranial disorders [intracranial hypertension, infection (EBV, HIV), neoplasm] Other (temporomandibular joint disorder, sinus infection)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cdh-090516233553-phpapp02/75/chronic-daily-headache-4-2048.jpg)

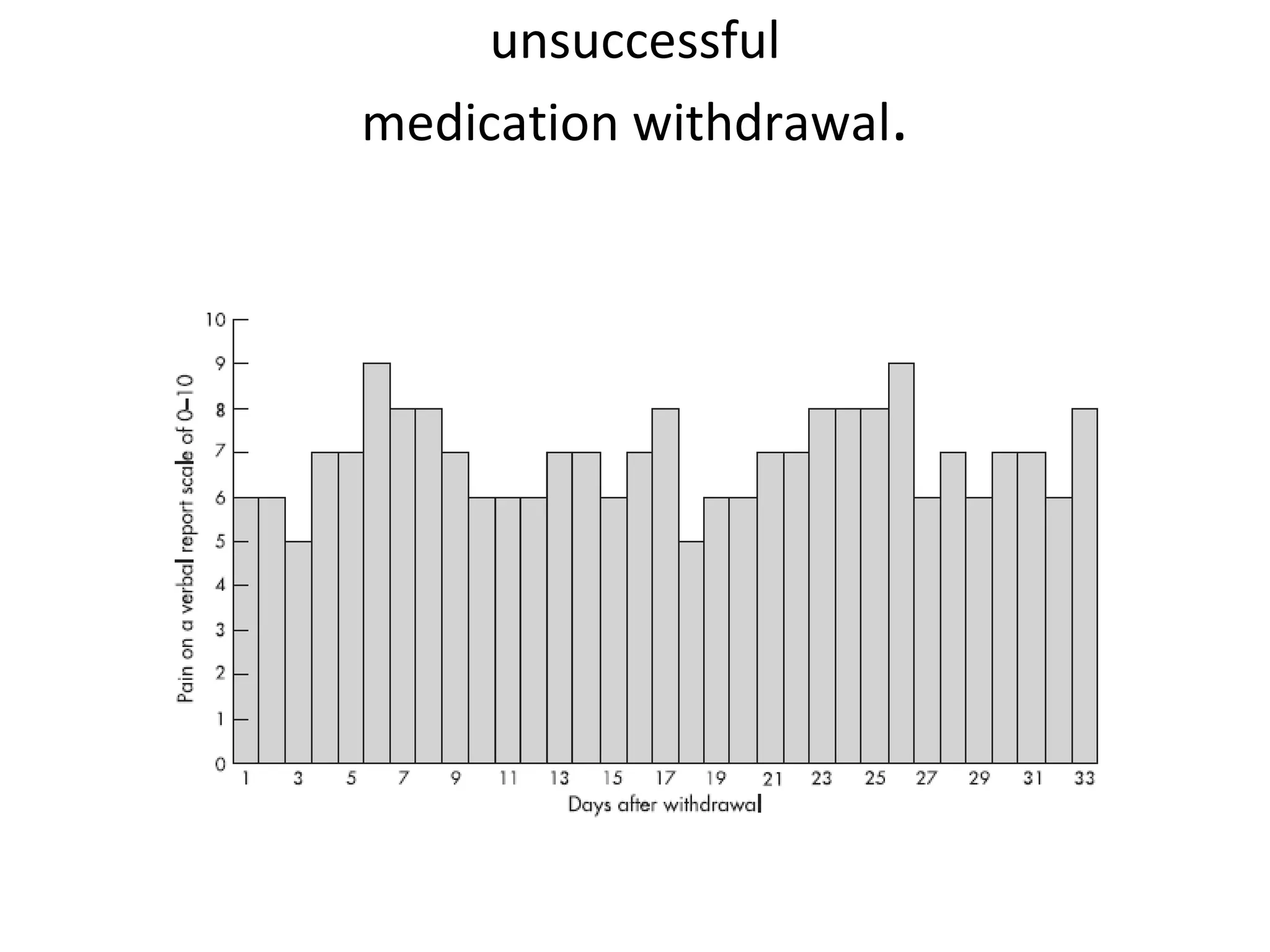

![Suggested Treatment of Transformed Migraine or Medication-Overuse Headache,NEJM 2006 Education, support, and close follow-up for 8–12 wk. Lifestyle modifications (quitting smoking, eliminating caffeine consumption, exercising, eating regular meals , and establishing regular sleep schedule). Behavioral therapy (relaxation therapy, biofeedback). Abrupt withdrawal of overused medications for acute headache, except barbiturates or opioids*. Prednisone (100 mg for 5 days [optional]). Acute-headache treatment (for moderate or severe headache). Non steroidal antiinflammatory drugs (e.g., 500 mg of naproxen sodium). Dihydroergotamine (1 mg) intranasally, subcutaneously, or intramuscularly. Antiemetics (10–20 mg of metoclopramide, 10 mg of prochlorperazine, or 4–8 mg of ondansetron). Preventive therapy.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cdh-090516233553-phpapp02/75/chronic-daily-headache-37-2048.jpg)