- Headaches are a common neurological problem and migraine is the most frequent diagnosis in patients presenting with headache.

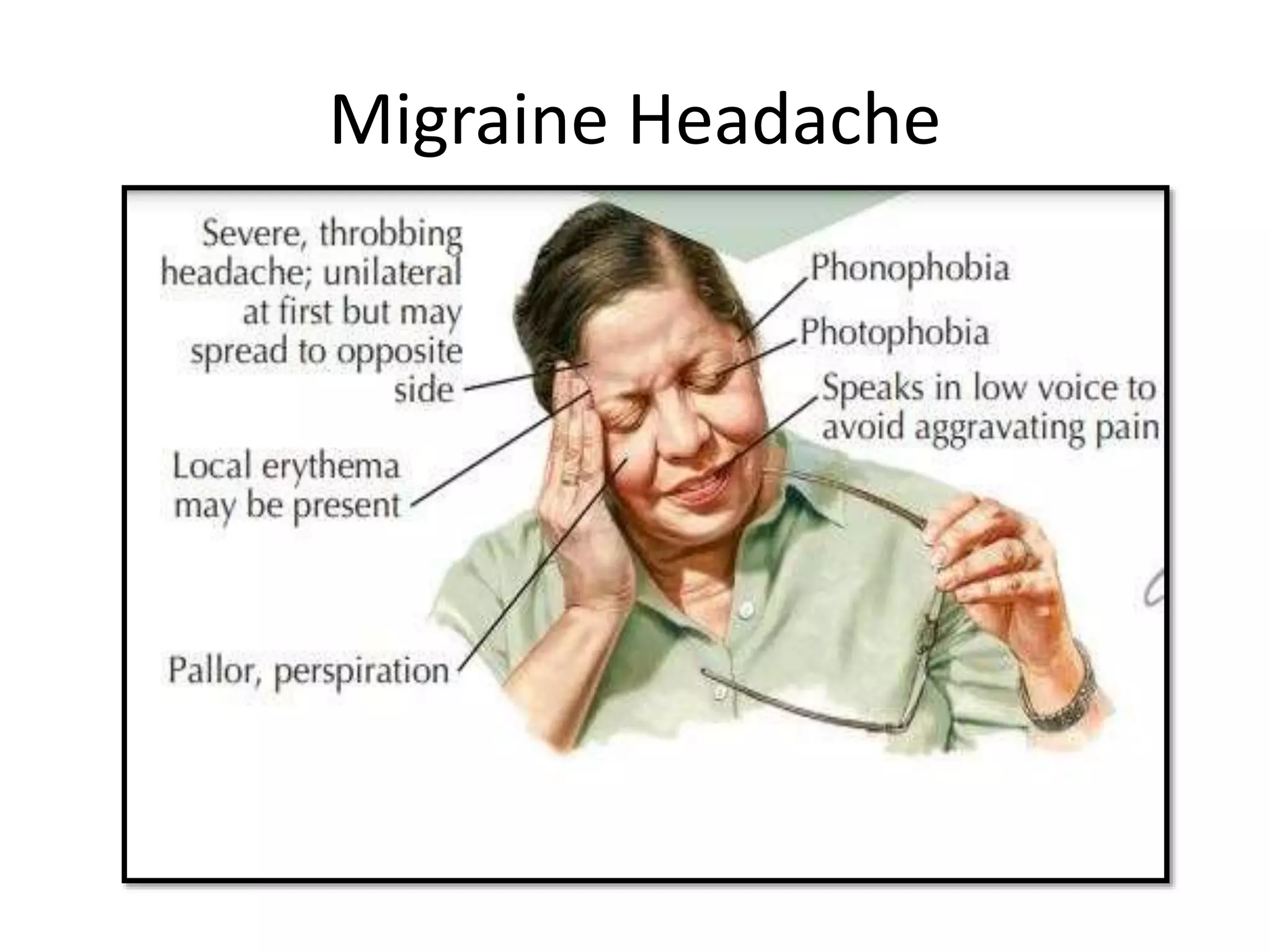

- Migraines affect 12-15% of the population and are characterized by distinct phases including prodrome, aura, headache, and postdrome. Common triggers include stress, hormones, sleep disturbances, and foods.

- Tension-type headaches are also very common and present as mild to moderate bilateral headaches without other symptoms. Treatment involves analgesics and behavioral therapies.

- Other primary headaches like cluster headaches and trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias present with short attacks of severe pain and autonomic symptoms. Emergency evaluation is needed for headaches with red flag symptoms.