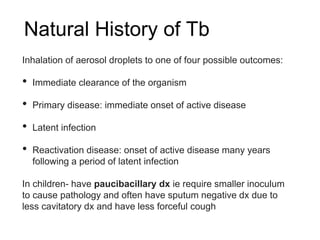

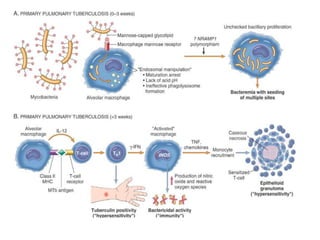

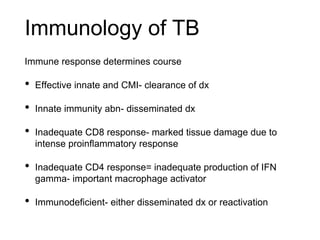

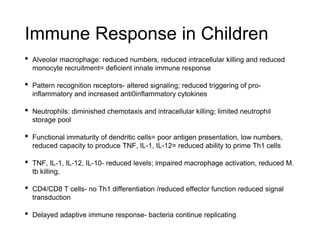

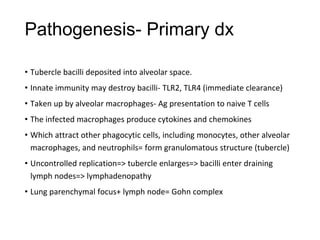

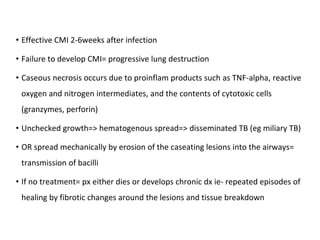

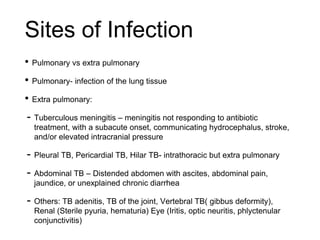

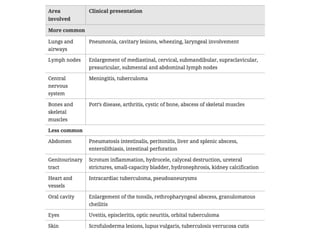

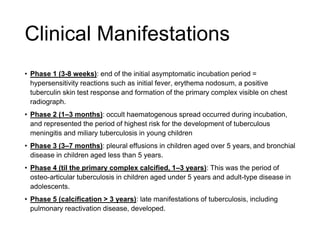

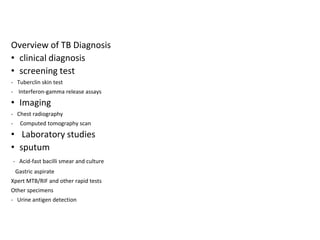

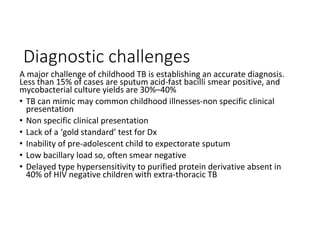

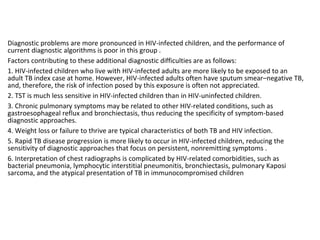

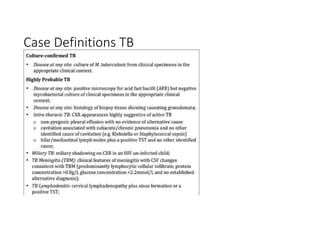

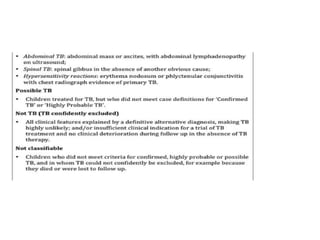

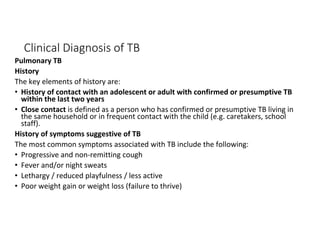

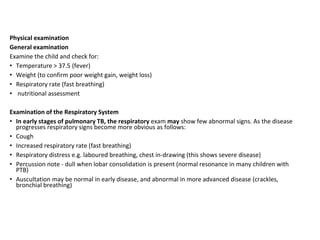

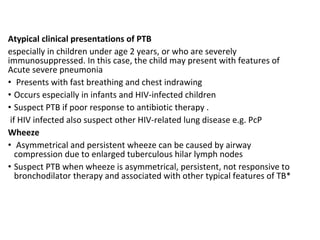

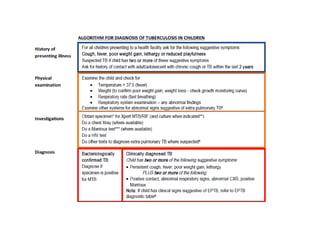

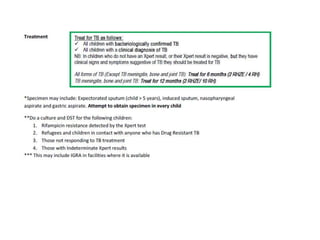

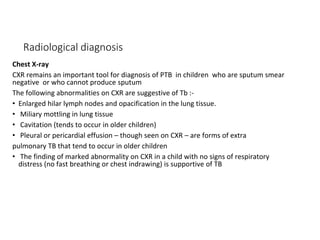

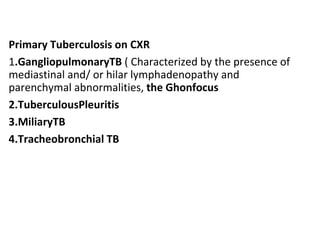

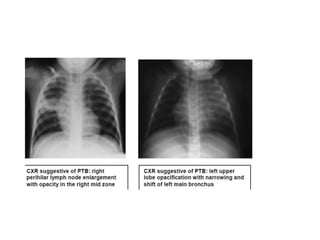

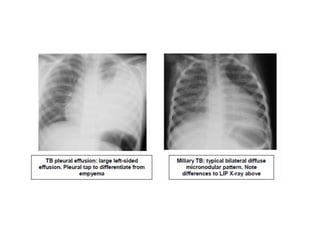

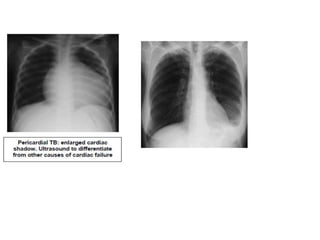

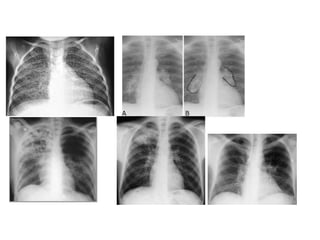

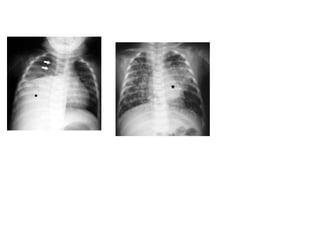

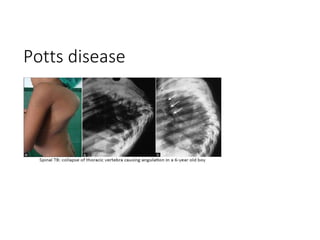

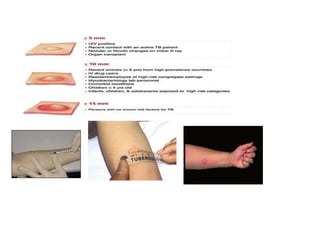

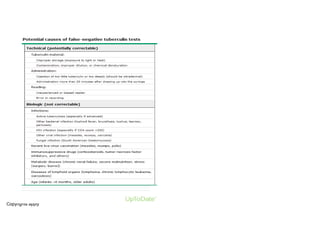

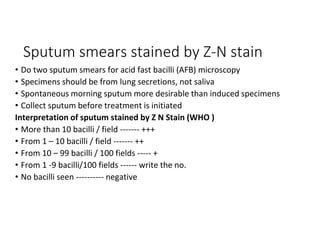

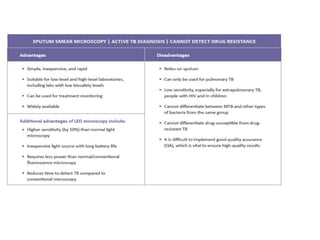

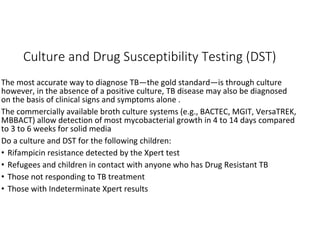

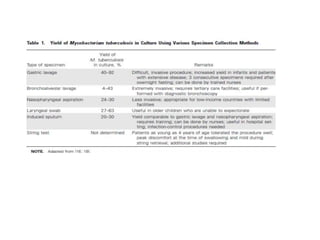

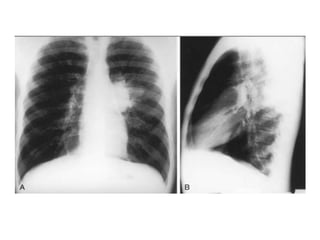

Tuberculosis (TB) in children can be difficult to diagnose due to non-specific symptoms, low bacterial loads, and inability to produce sputum. The document discusses the pathogenesis and immune response to TB in children. Key points include that children have a less developed innate and adaptive immune response, leading to atypical presentations. Diagnosis relies on clinical history of exposure and symptoms, imaging, and microbiological confirmation from specimens like gastric aspirates since sputum samples are often smear-negative. HIV co-infection further complicates the diagnosis of childhood TB.