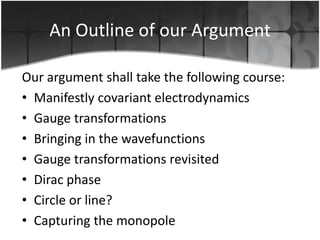

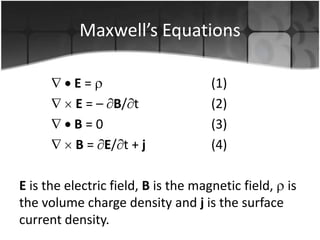

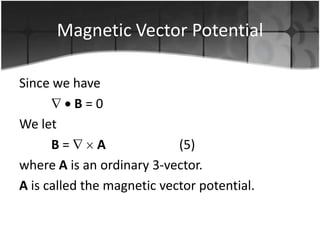

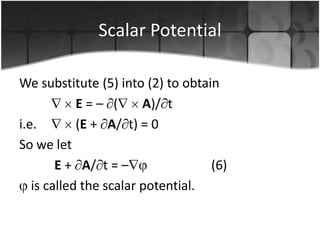

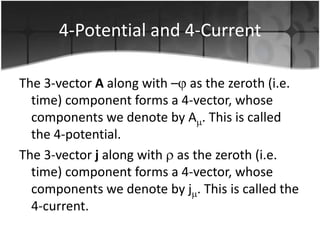

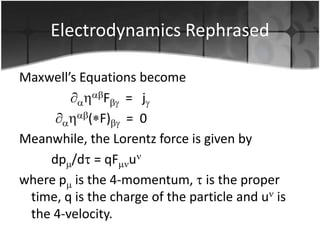

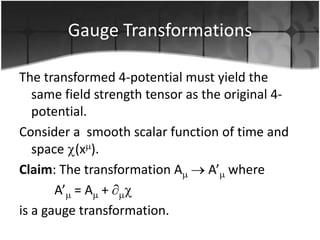

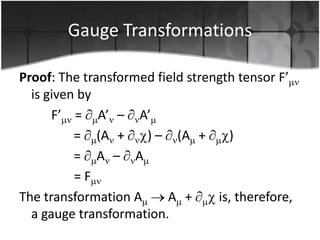

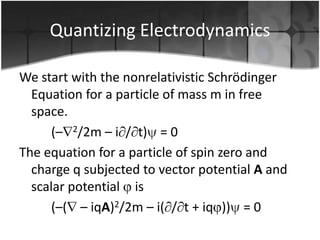

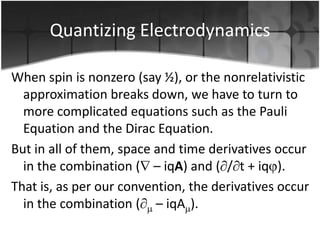

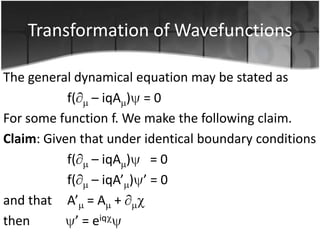

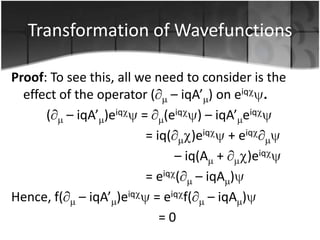

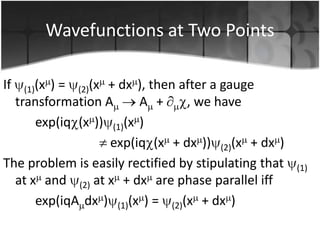

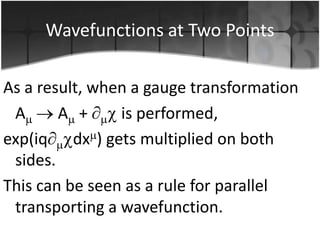

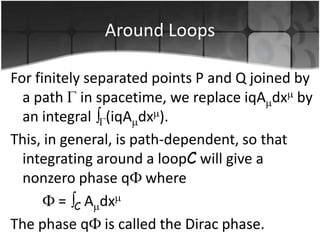

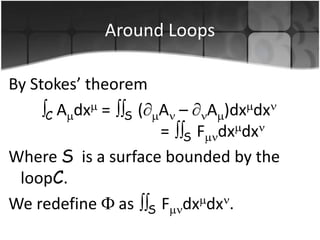

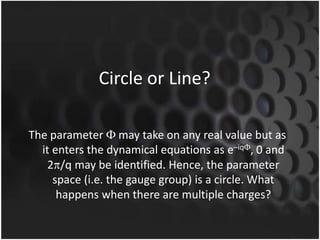

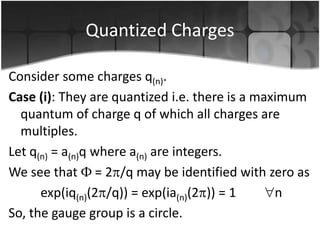

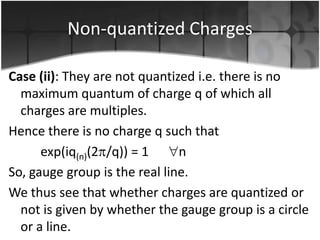

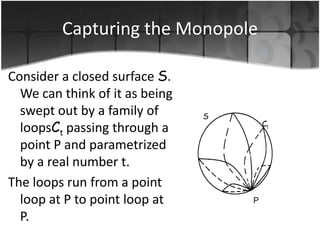

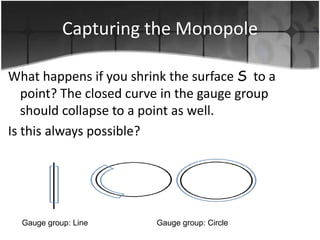

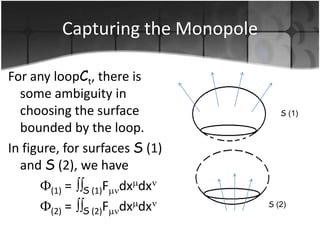

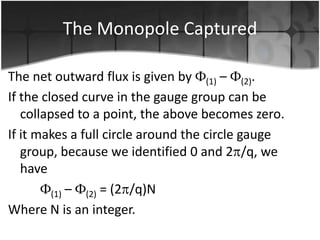

The document discusses the quantization of electric charge and the theoretical implications of magnetic monopoles, referencing Paul Dirac's work from 1931. It outlines key concepts in electrodynamics, gauge transformations, and the relationship between charge quantization and magnetic monopoles, ultimately leading to the Dirac quantization condition. The paper emphasizes that the existence of magnetic monopoles elegantly explains the necessity of quantized electric charge, although experimental evidence of monopoles remains elusive.