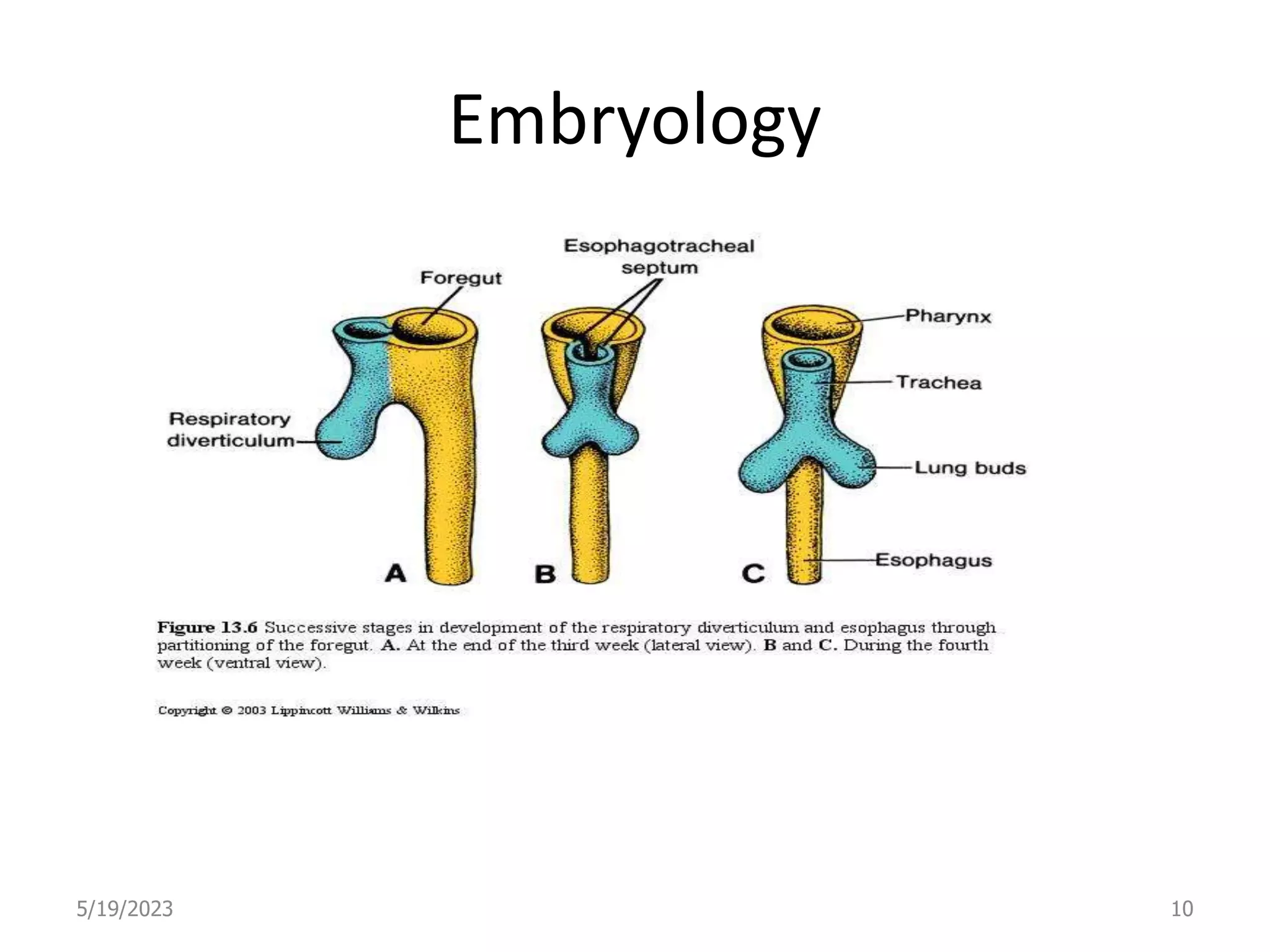

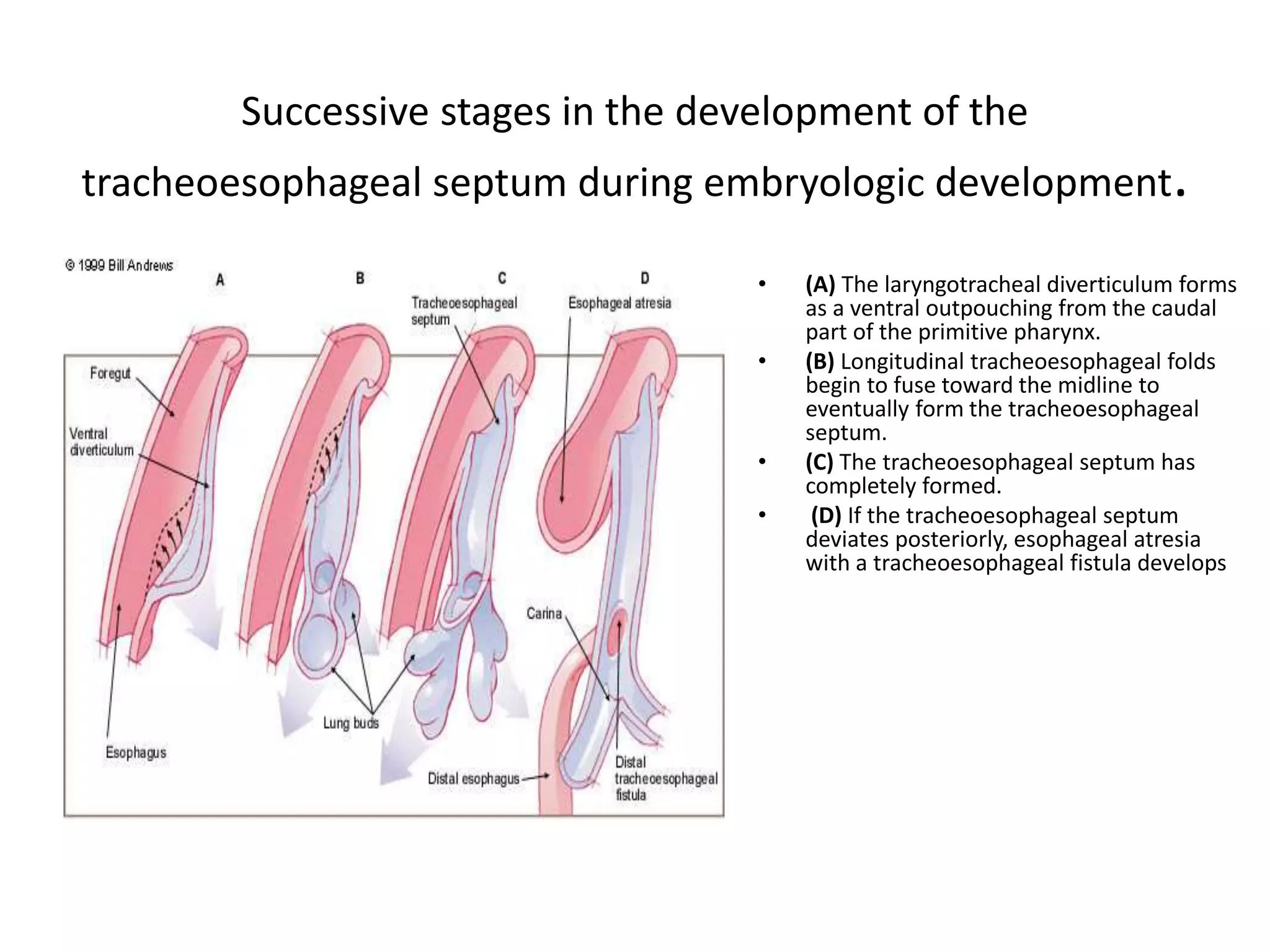

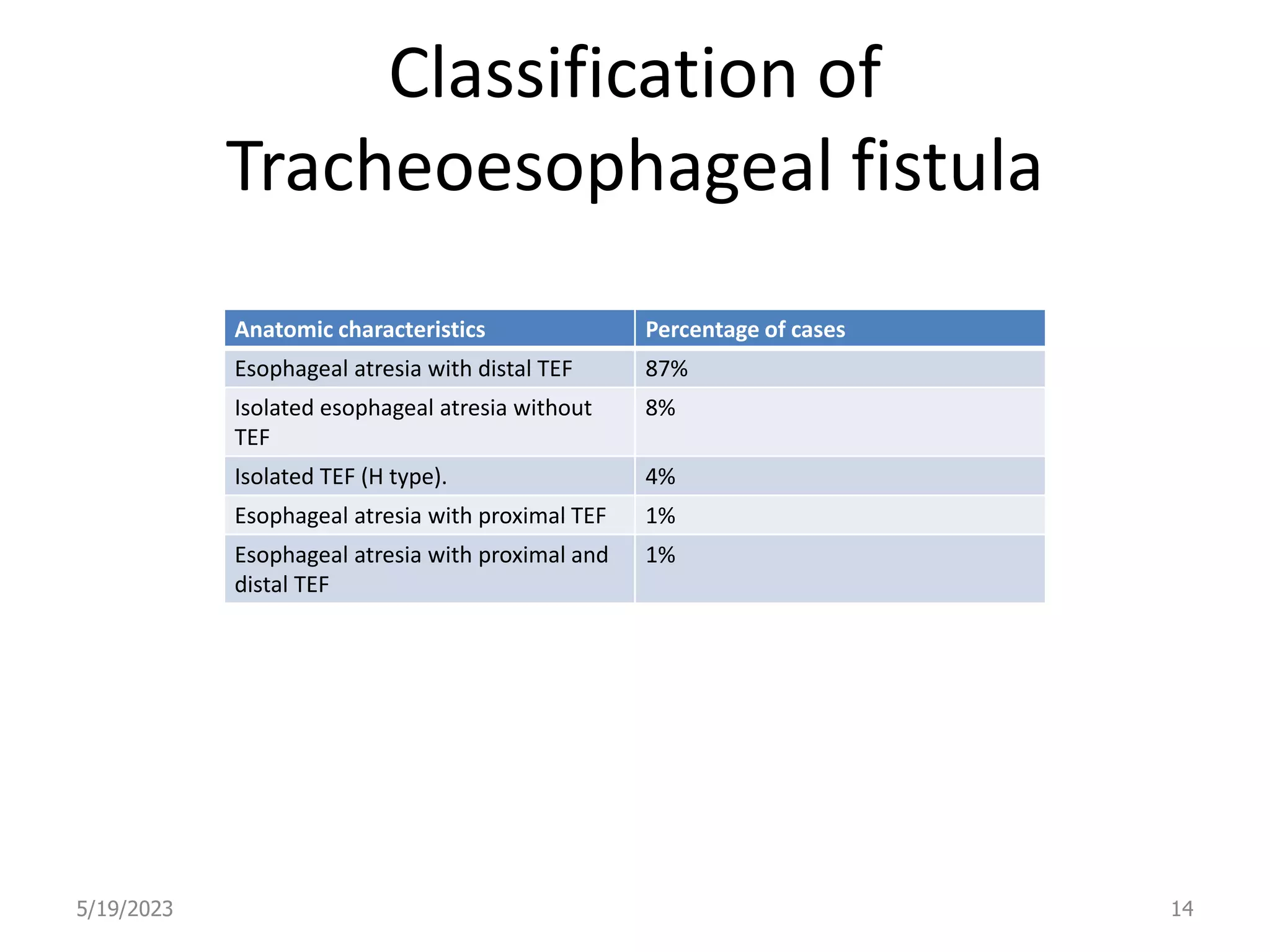

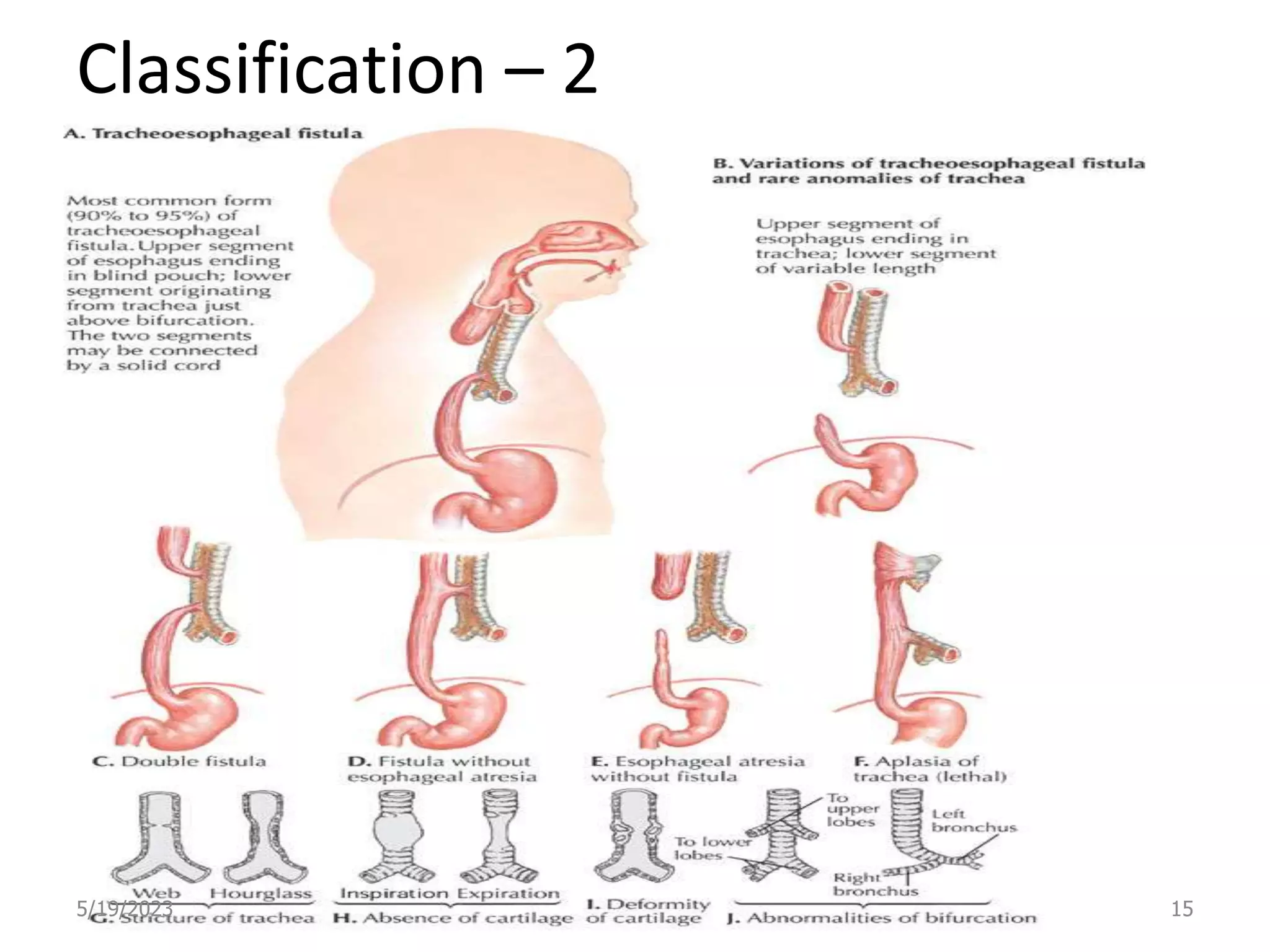

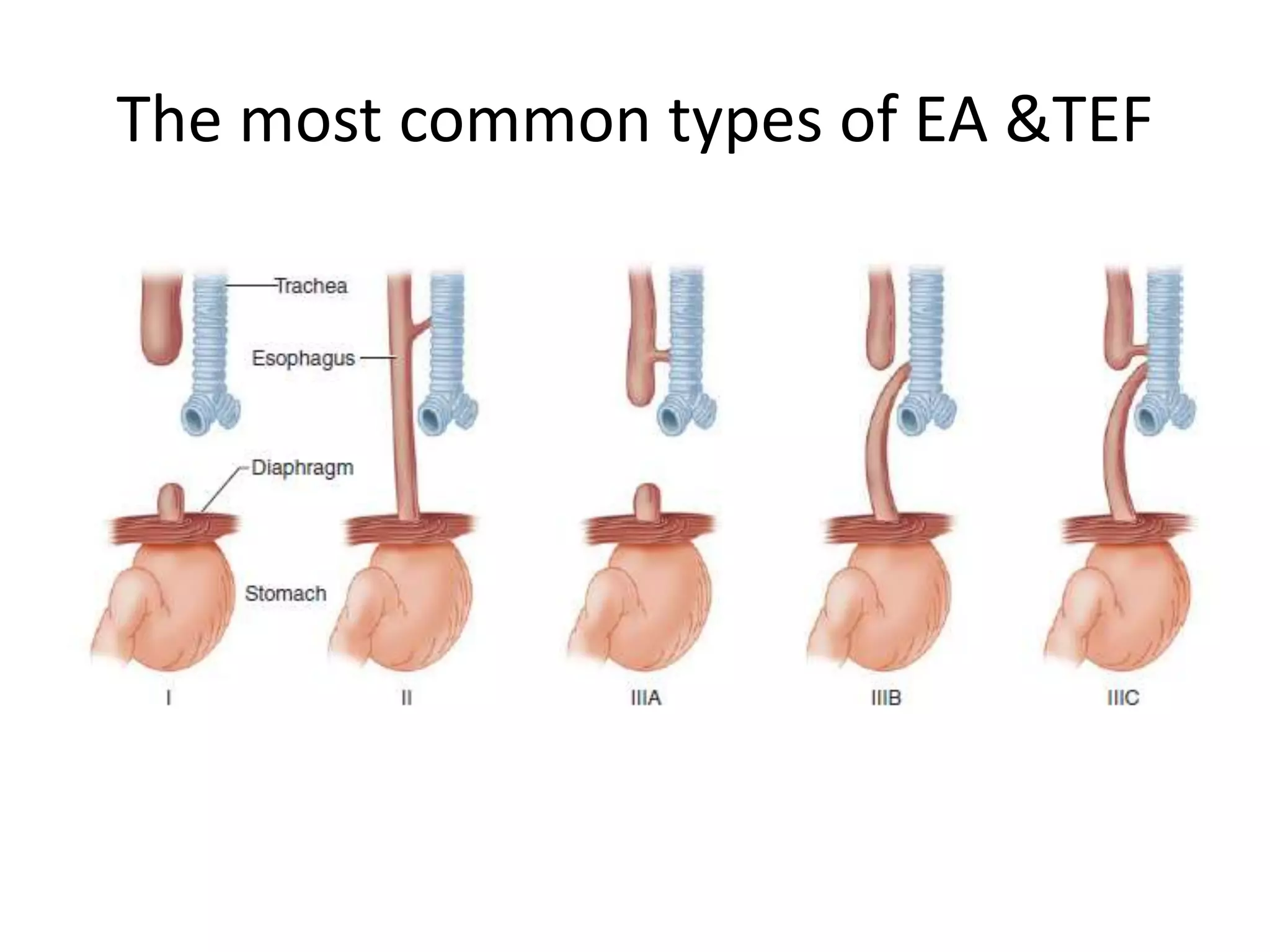

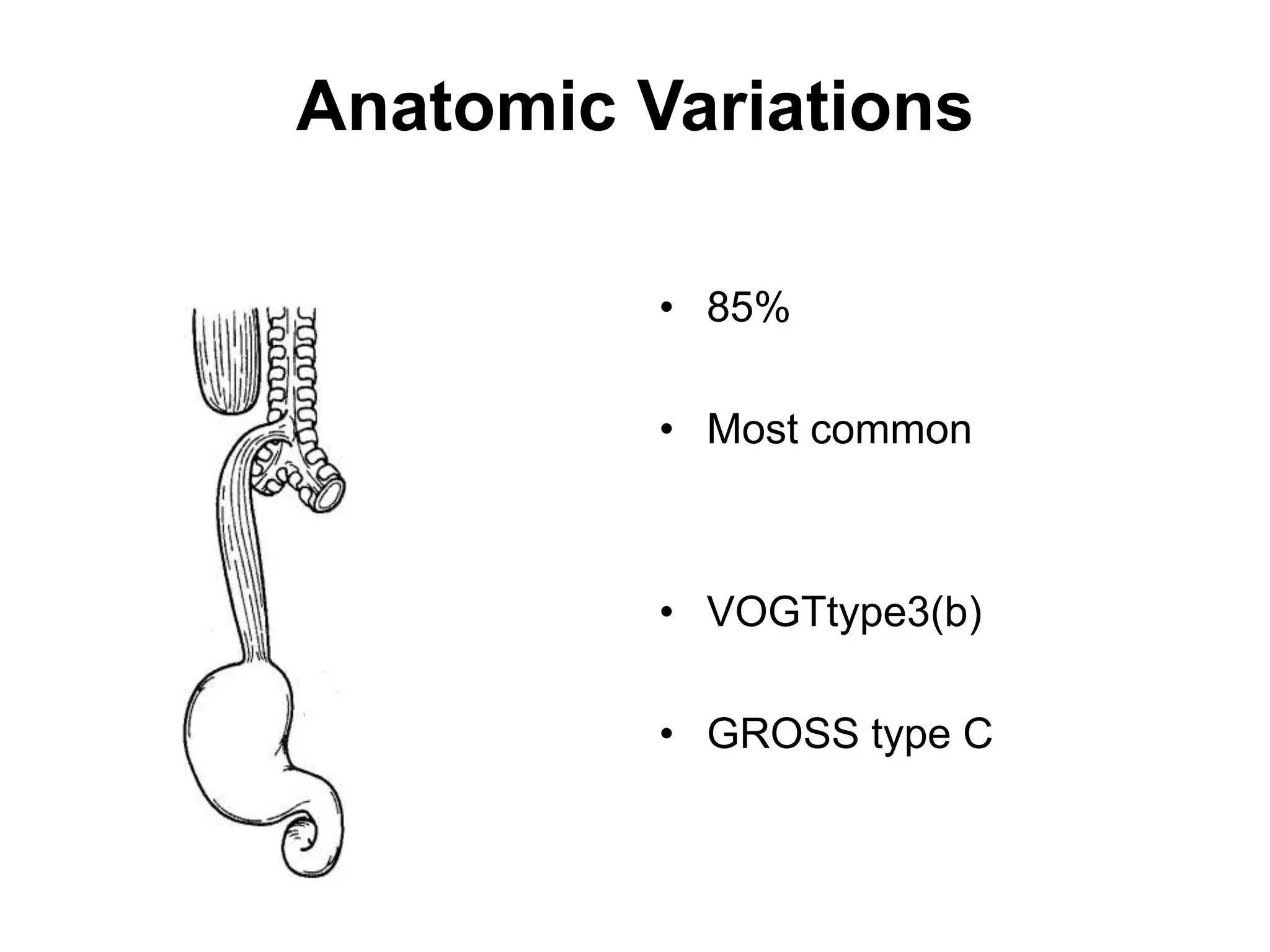

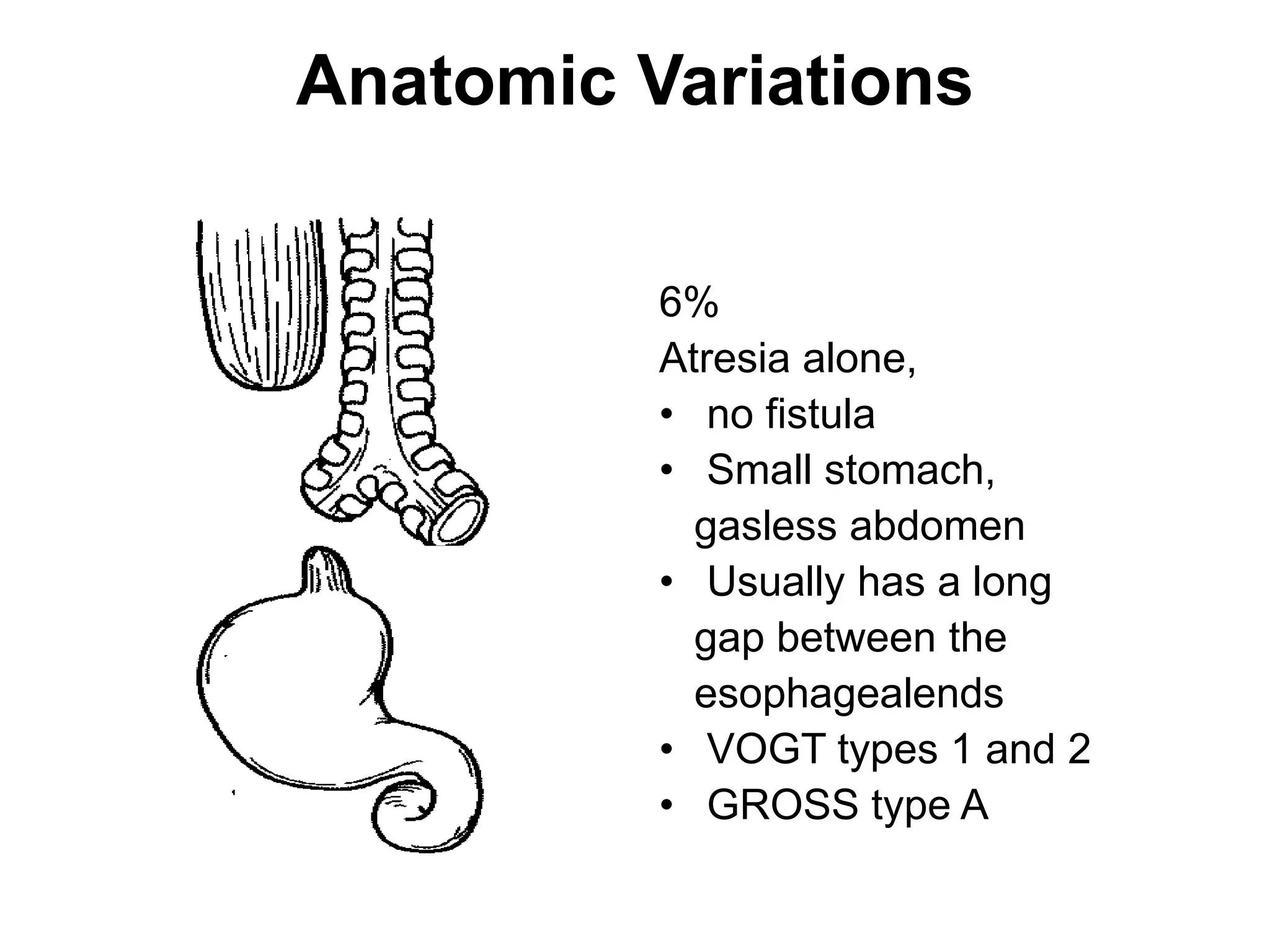

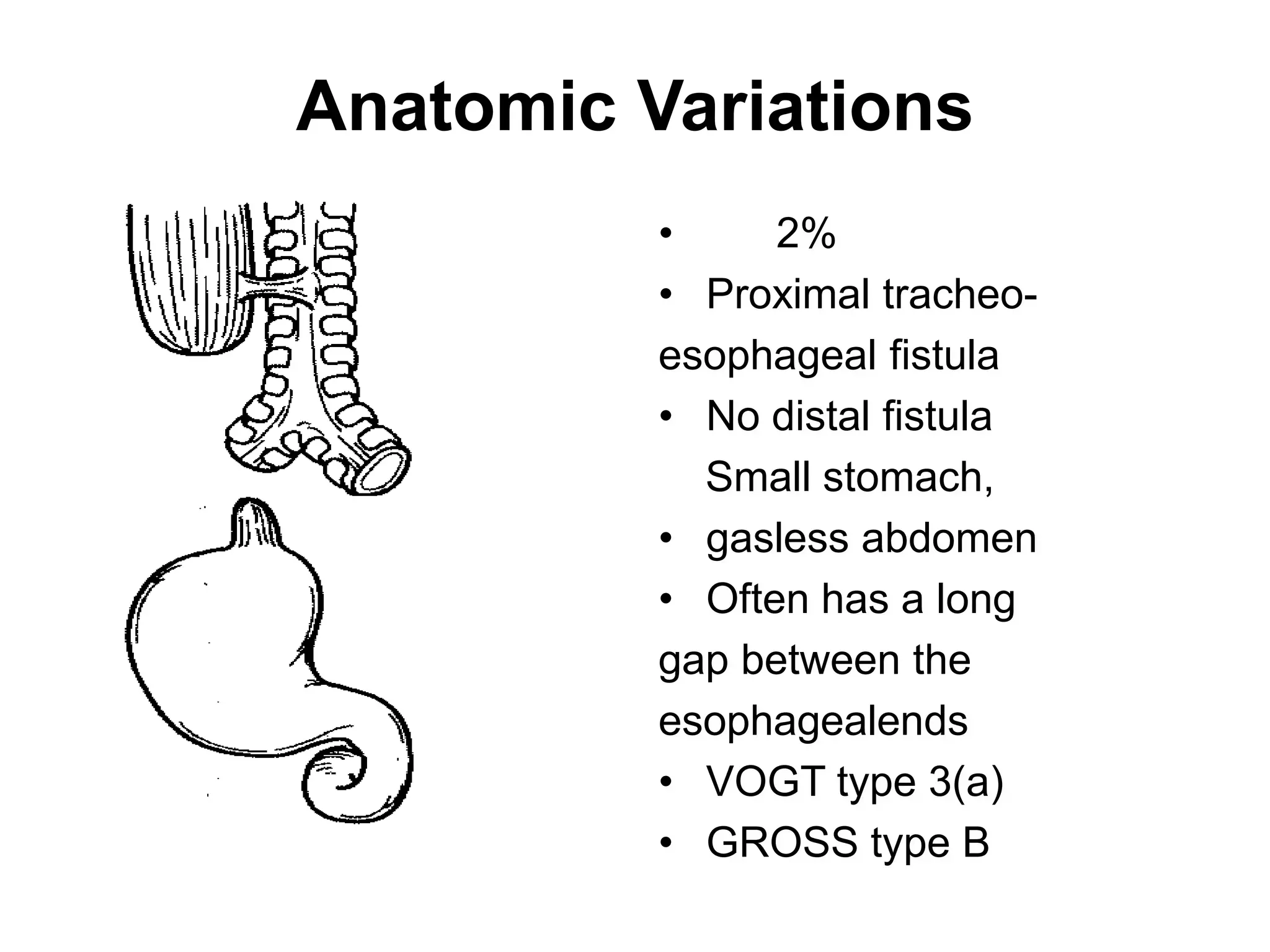

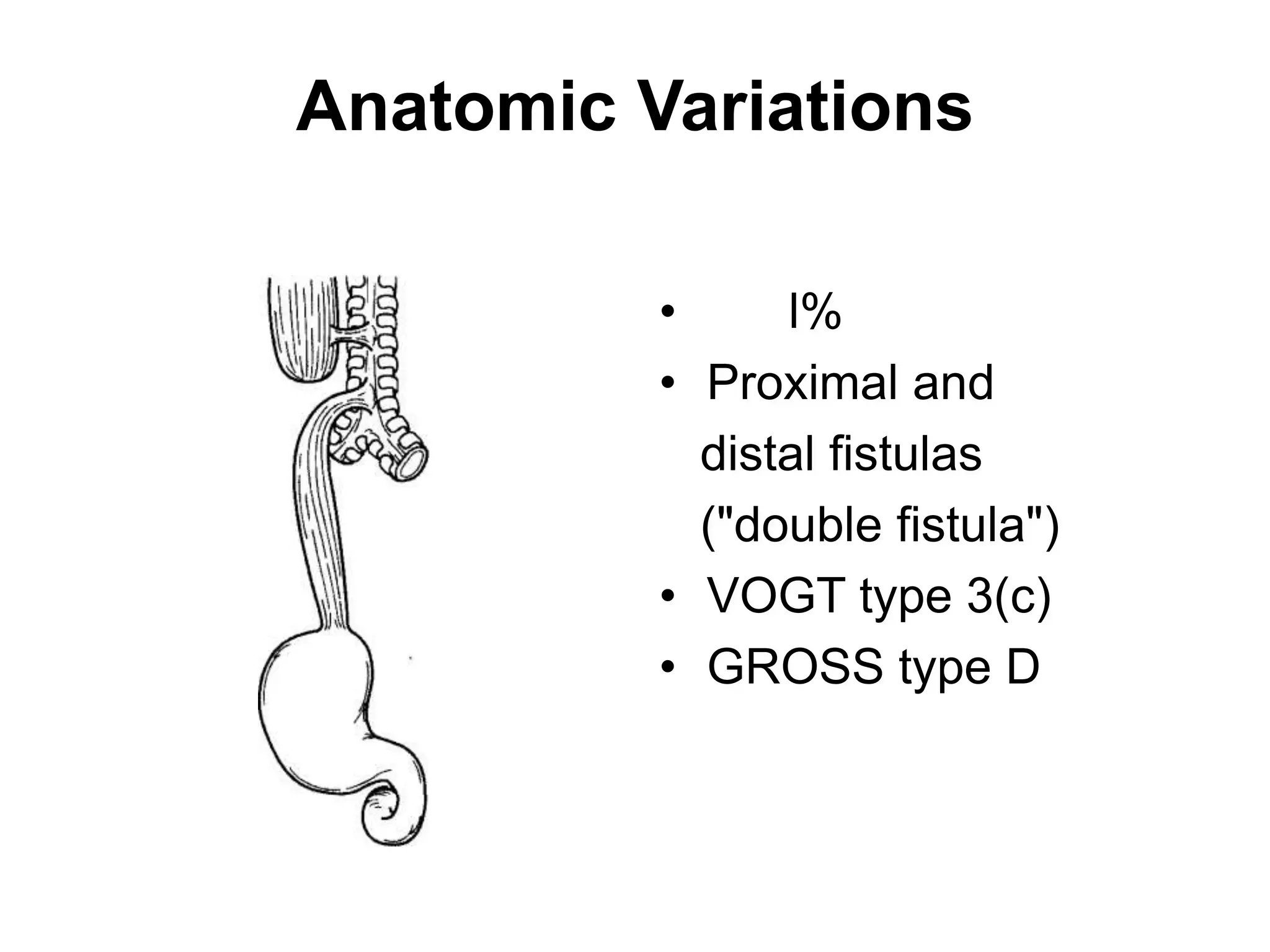

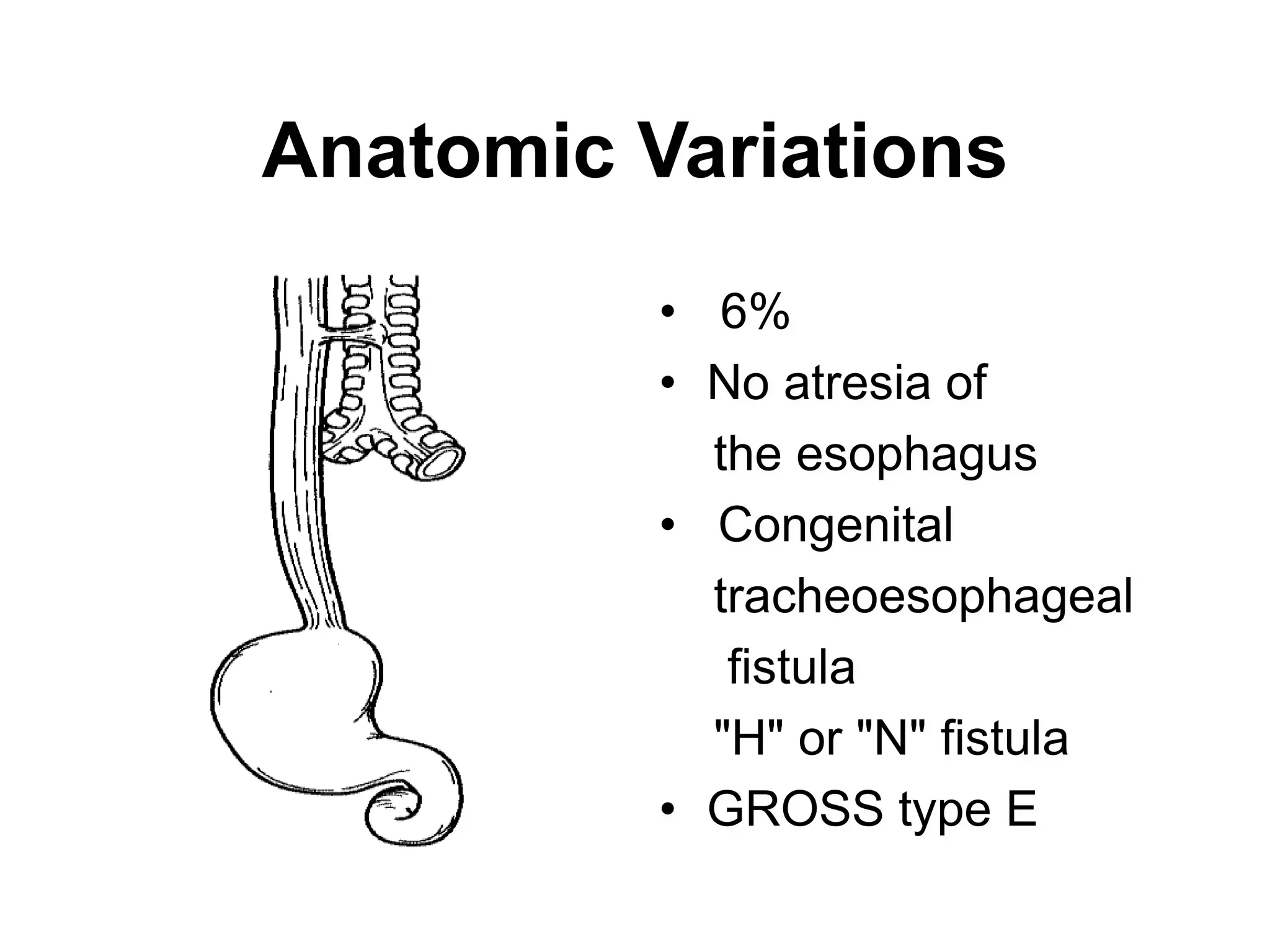

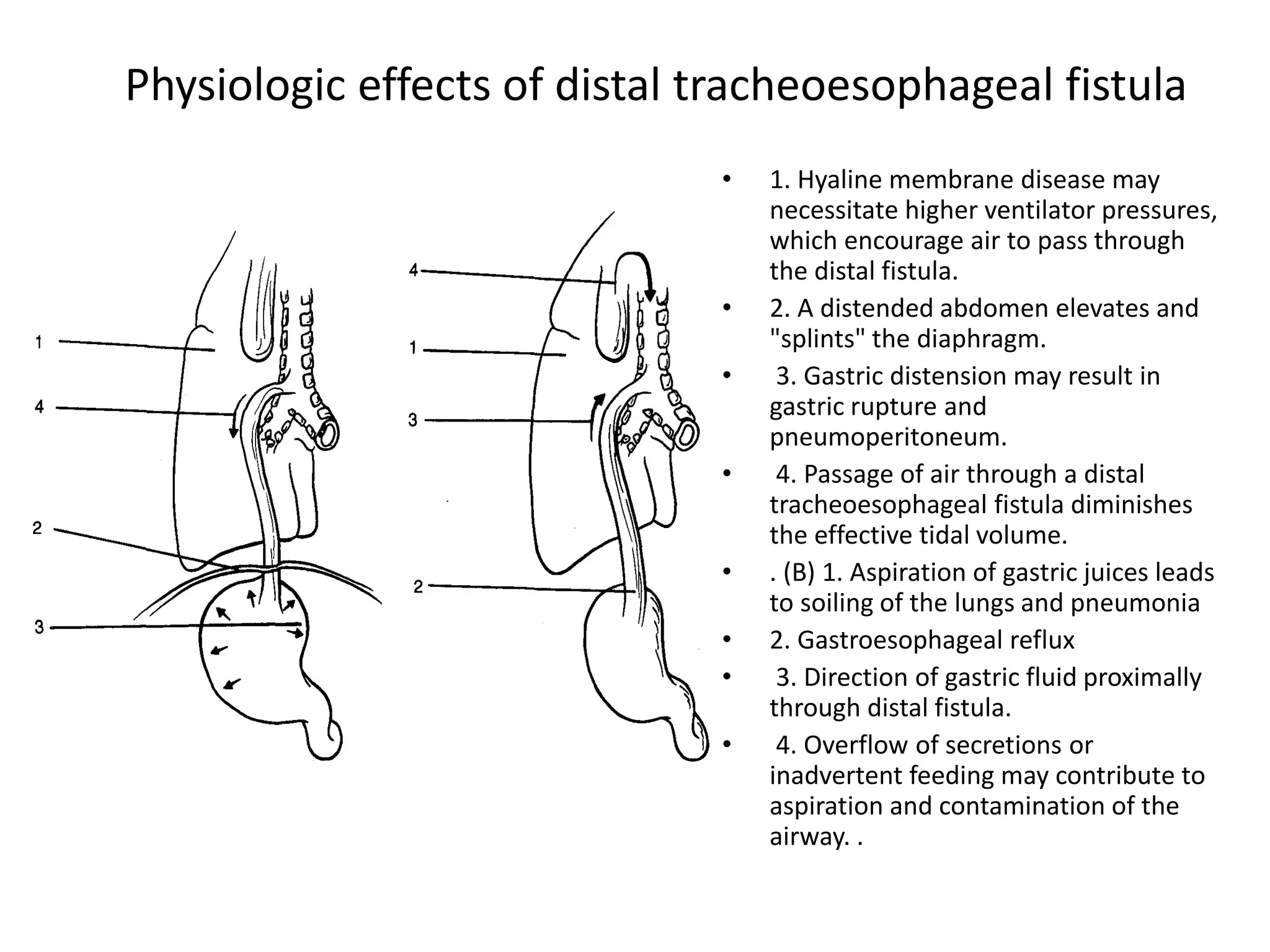

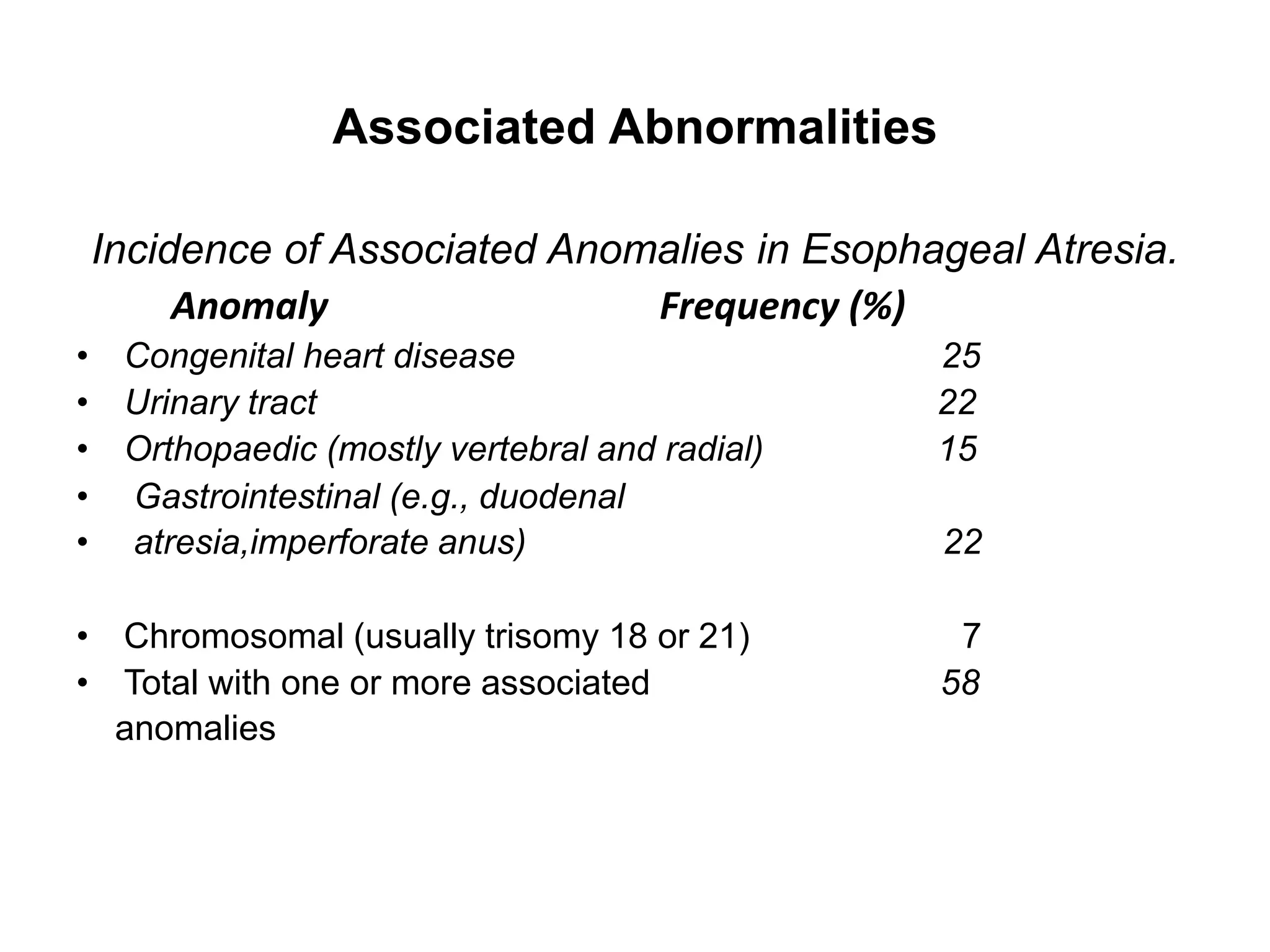

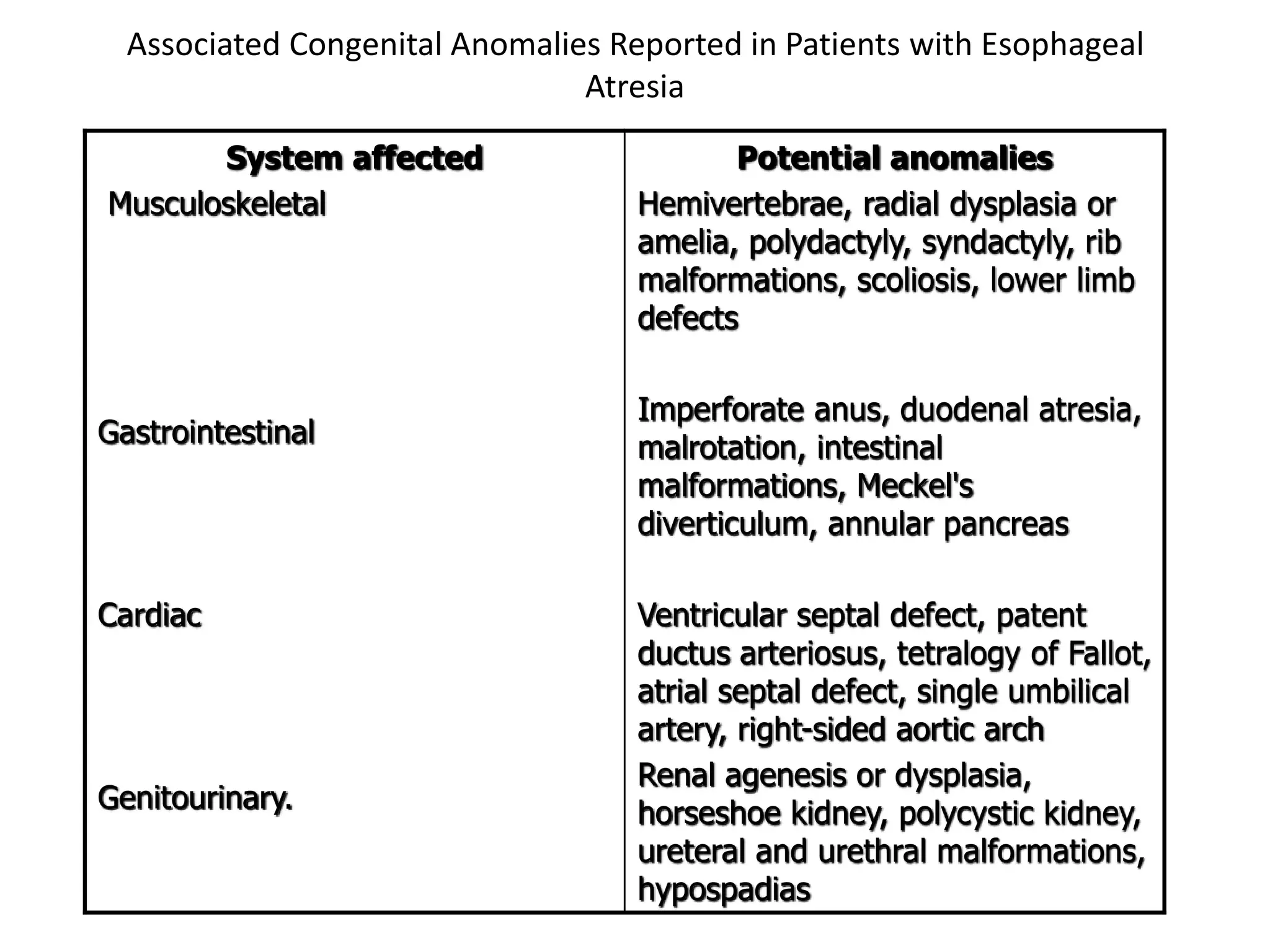

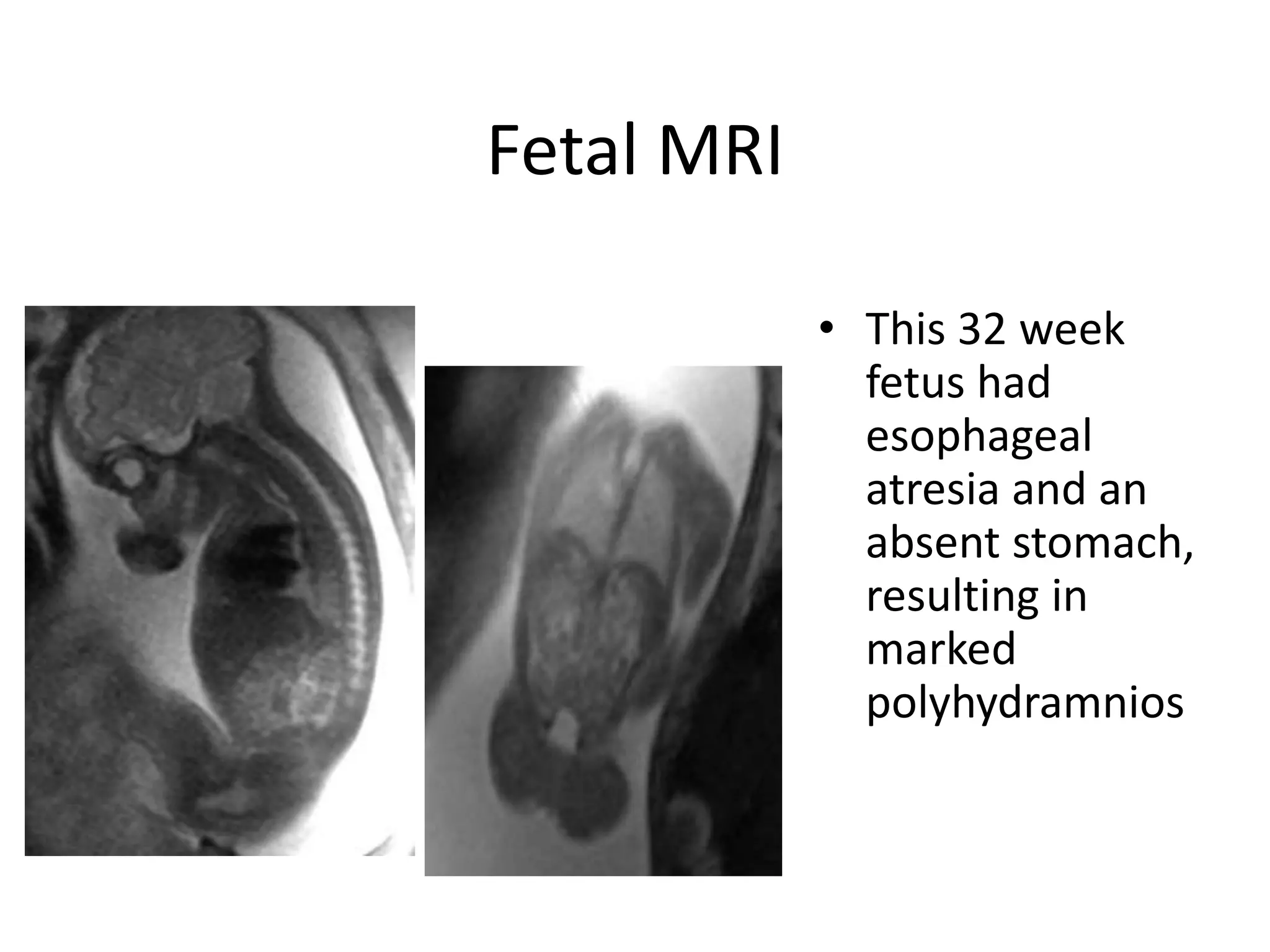

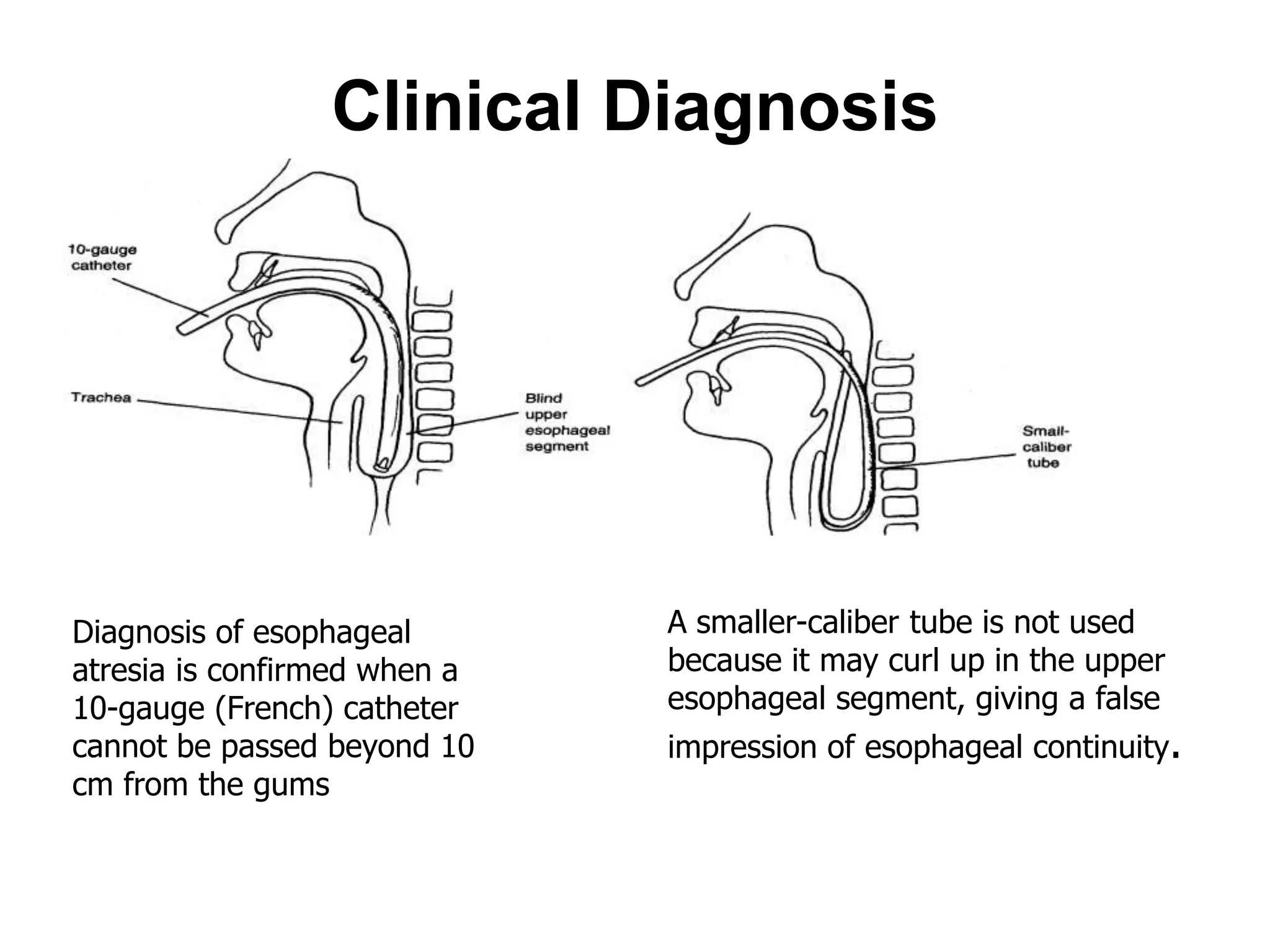

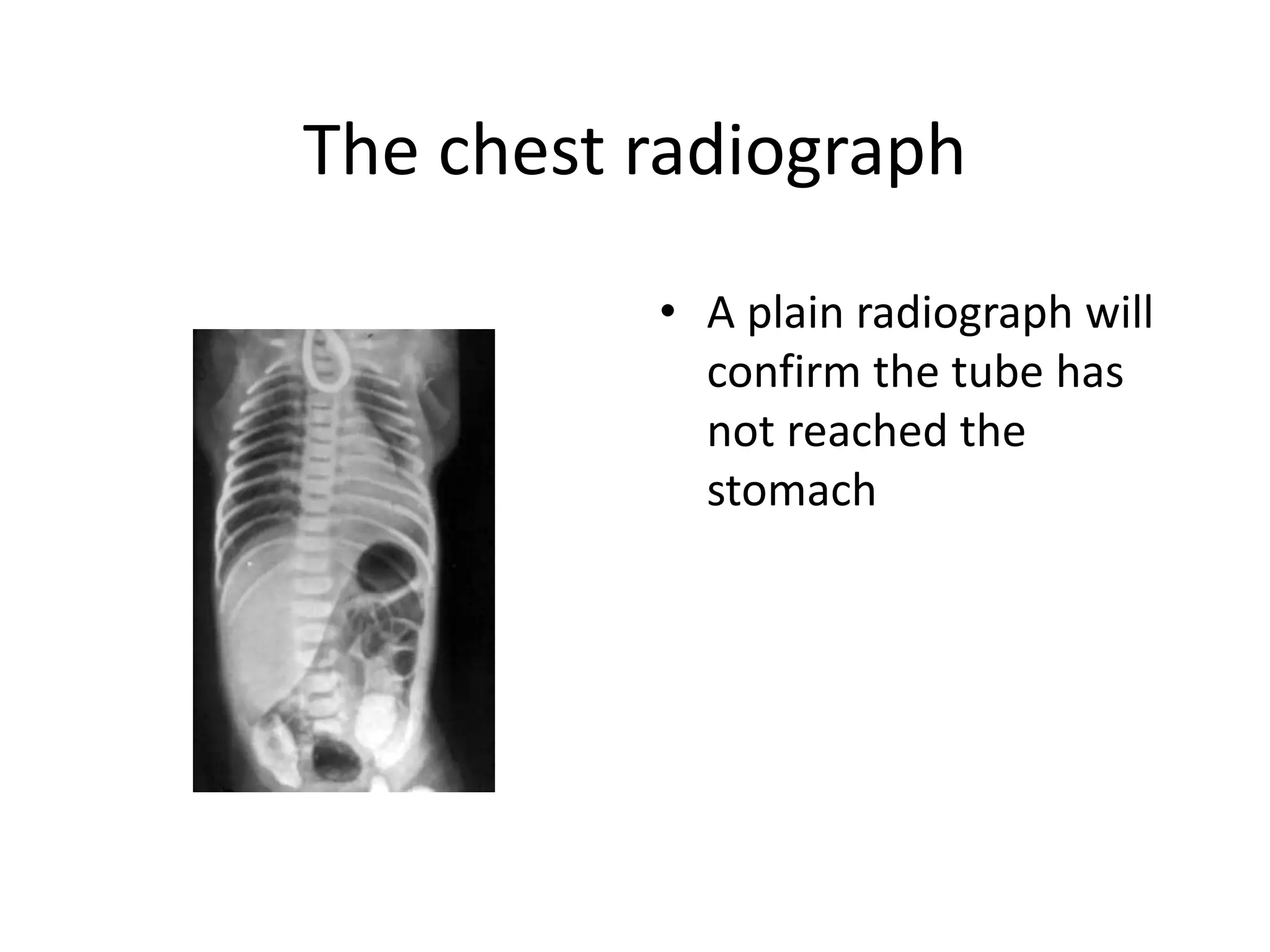

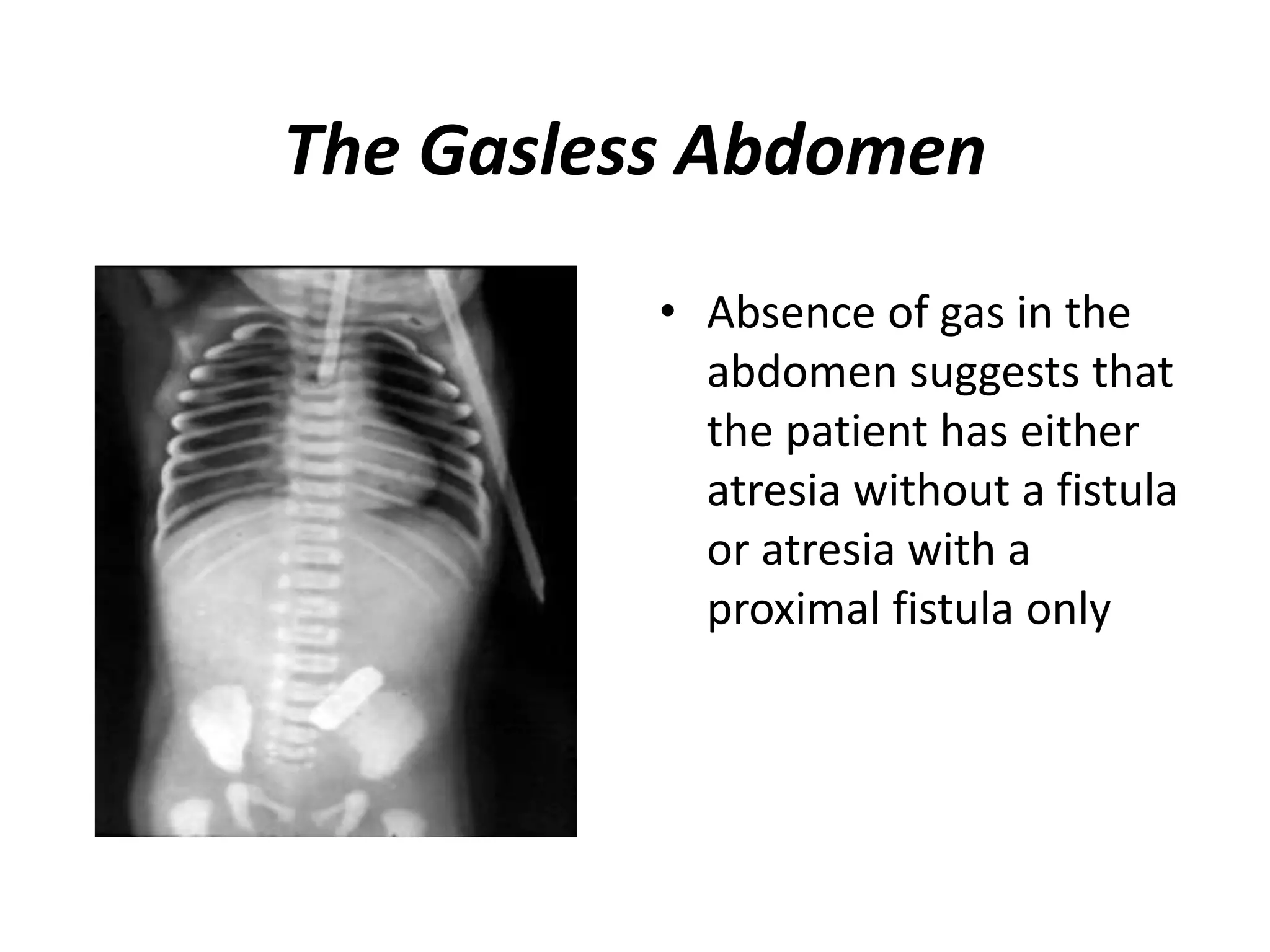

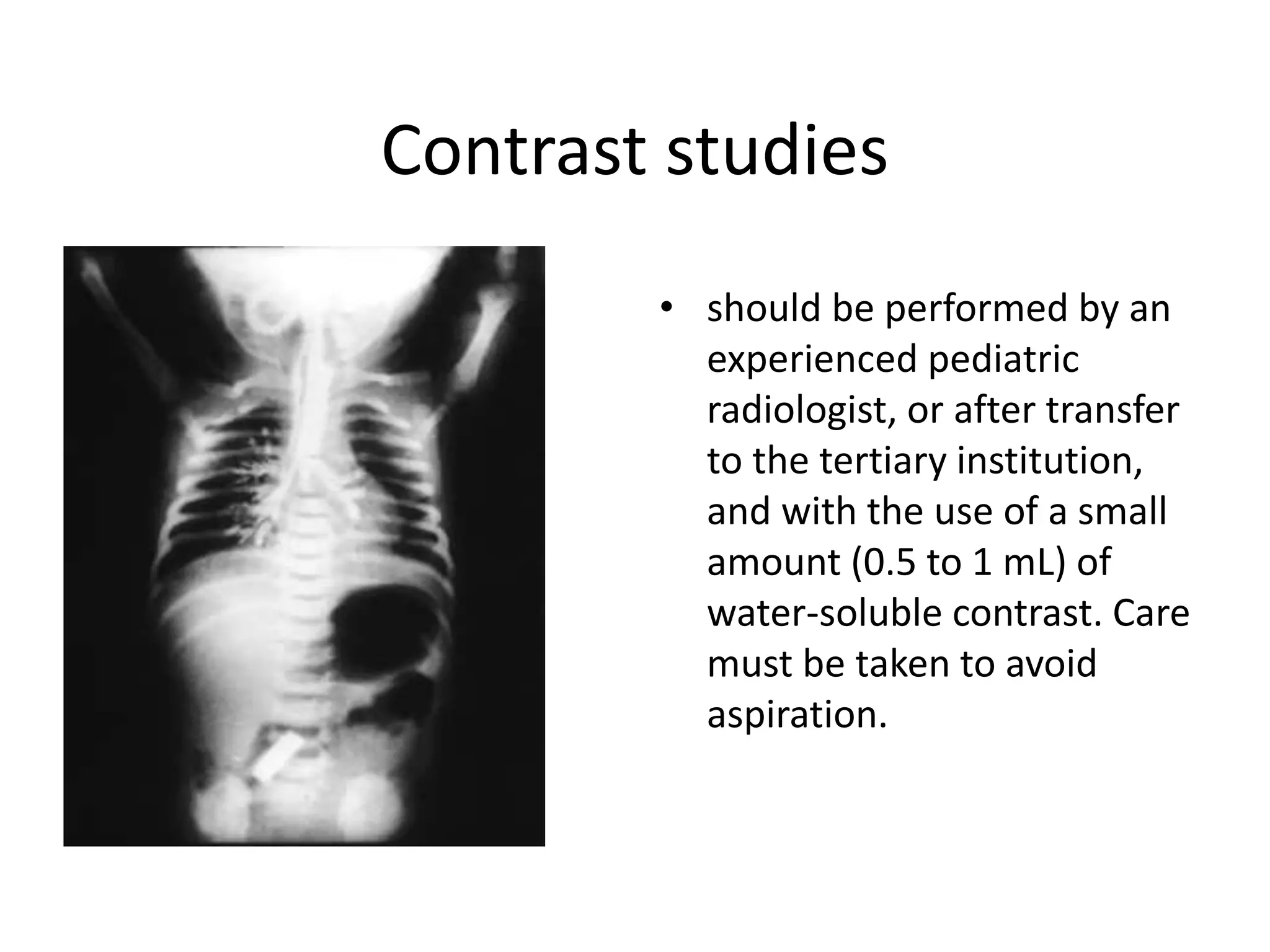

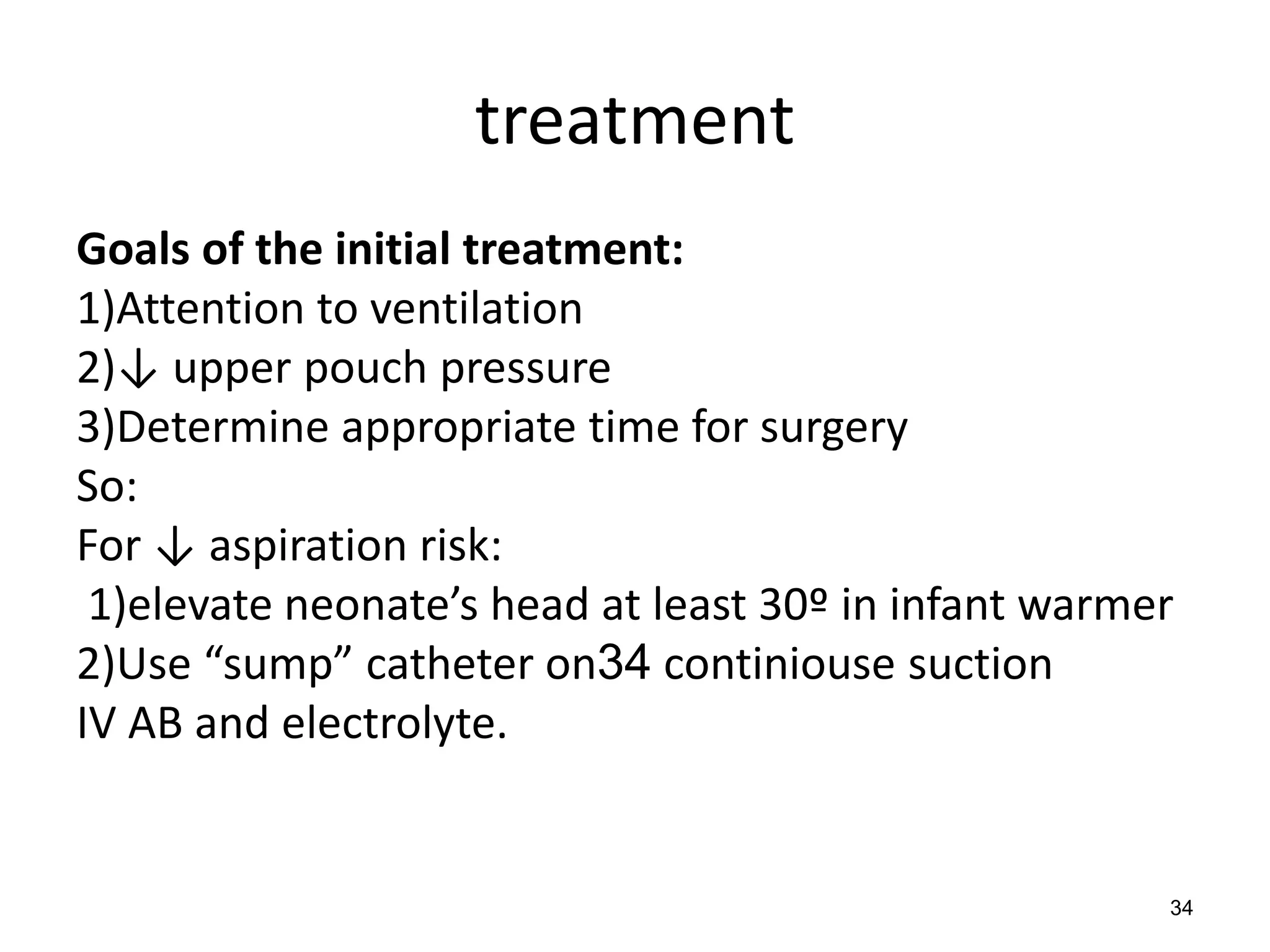

This document discusses esophageal atresia and tracheoesophageal fistula (EA/TEF). It begins by defining EA/TEF and providing incidence rates. EA occurs when the esophagus is not fully developed and is missing a portion, while TEF is an abnormal connection between the trachea and esophagus. EA occurs in association with TEF in about 90% of cases. The document then covers the embryology, classification, associated anomalies, diagnosis and management of EA/TEF. It describes the development of the esophagus and trachea in utero and how defects can result in EA/TEF. Classification systems divide EA/TEF based on anatomical characteristics. Associated anomalies are common, particularly