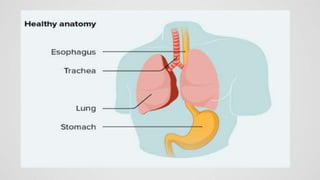

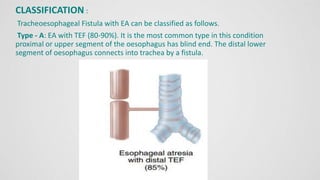

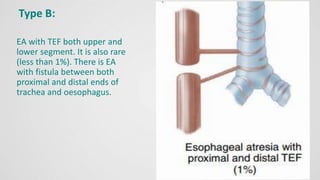

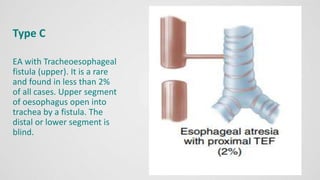

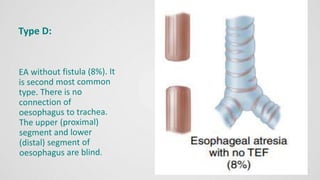

Tracheoesophageal fistula (TEF) is an abnormal connection between the trachea and esophagus, often associated with esophageal atresia, occurring in approximately 1 in 3,500 live births globally. The diagnosis involves clinical presentation, imaging tests, and requires immediate medical intervention, typically surgical repair, which is crucial for the infant's survival. Complications may include respiratory distress and gastroesophageal reflux, but the survival rate post-surgery can be as high as 100% in healthy infants.