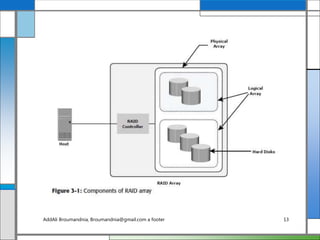

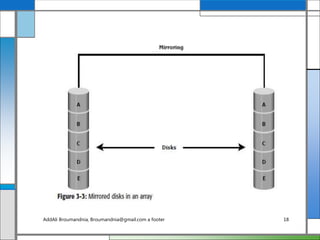

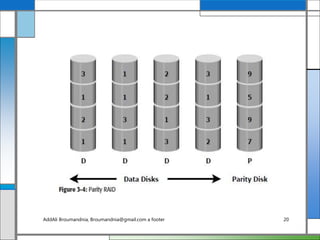

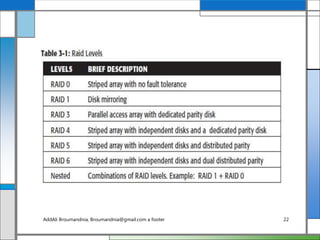

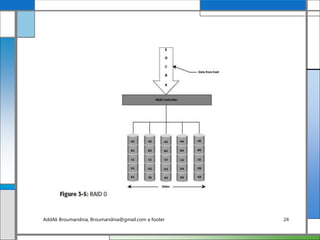

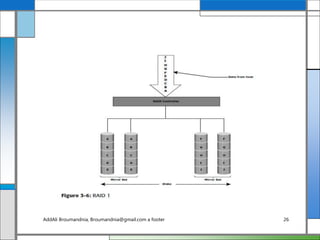

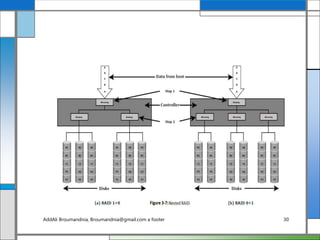

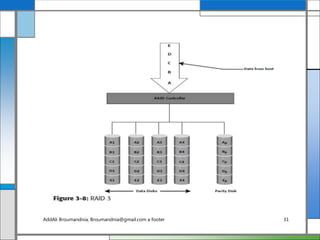

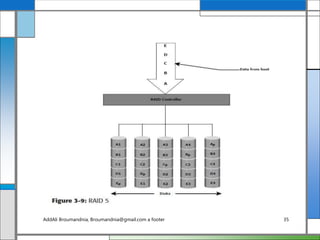

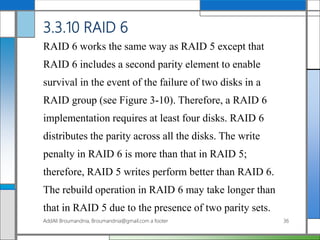

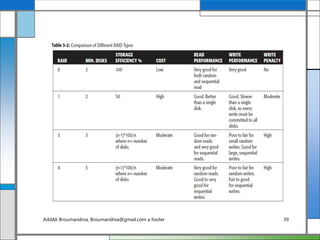

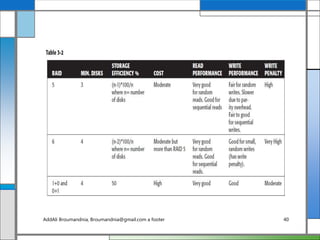

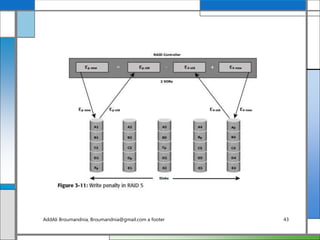

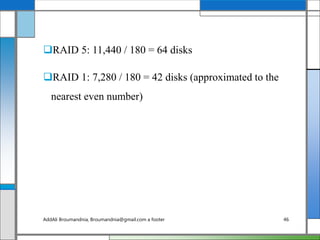

This document discusses data protection using RAID (Redundant Array of Independent Disks) technology. It describes the different types of RAID implementations including software RAID, hardware RAID, and various RAID levels such as RAID 0, 1, 3, 4, 5 and 6. These RAID levels use techniques such as striping, mirroring and parity to provide data redundancy and availability while improving performance. The document provides details on how each RAID level works and the benefits it provides for different application needs.