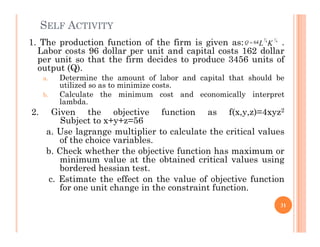

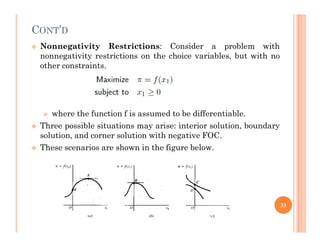

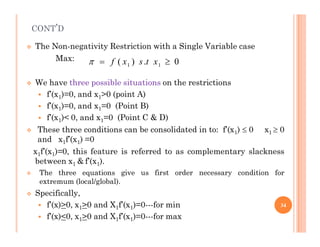

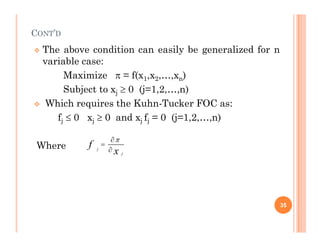

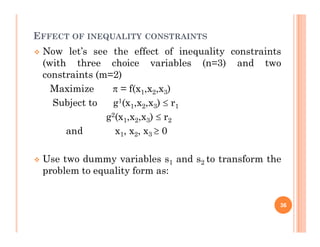

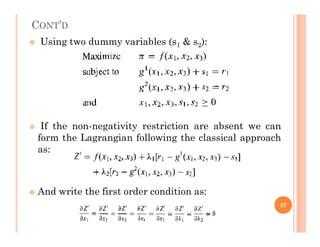

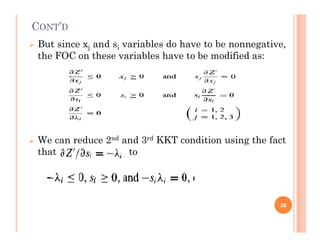

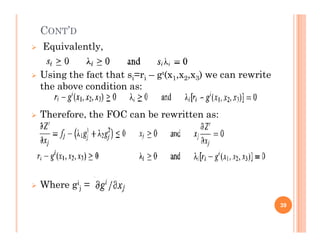

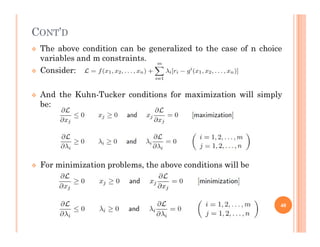

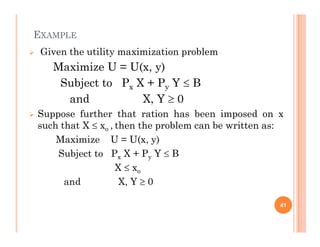

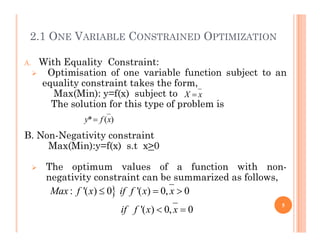

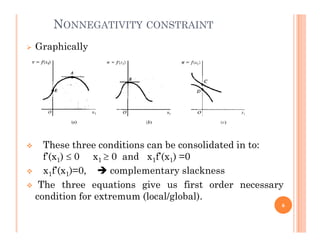

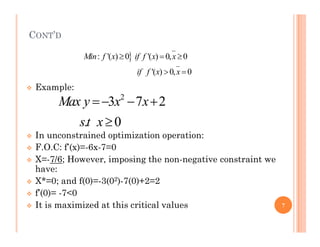

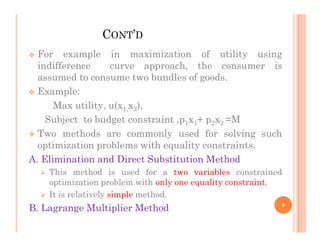

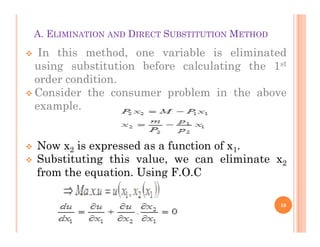

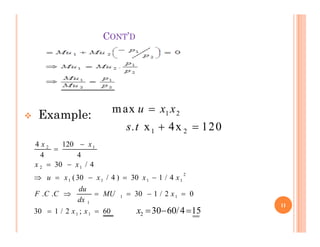

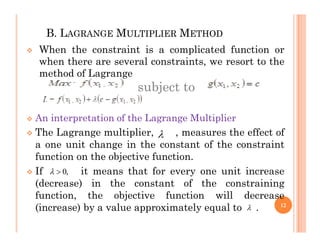

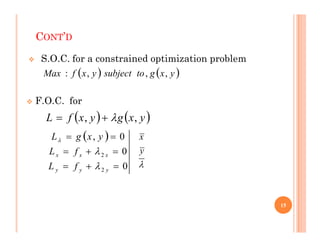

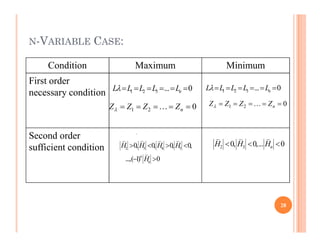

Chapter 2 discusses constrained optimization in economic contexts, where optimization must consider specific constraints such as resource availability. It explores one-variable and two-variable optimization problems with equality constraints using methods like elimination and Lagrange multipliers. The chapter emphasizes the importance of constraints on scope and method in maximizing or minimizing economic functions.

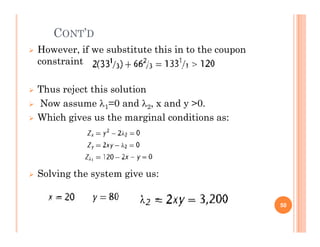

![N-VARIABLE CASE:

1 2

( , , , )

n

z f x x x

1 2

( , , , )

n

g x x x c

1 2 1 2

( , , , ) [ ( , , , )]

n n

z f x x x c g x x x

Objective function:

subject to

with

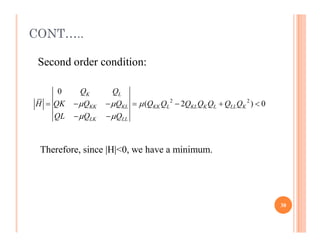

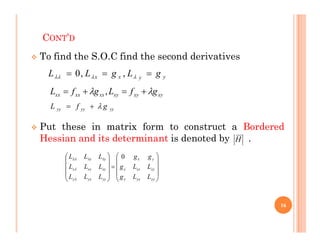

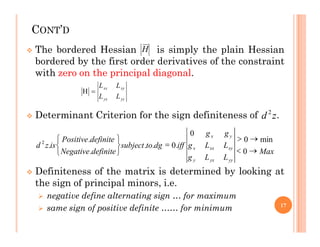

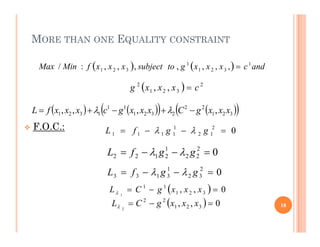

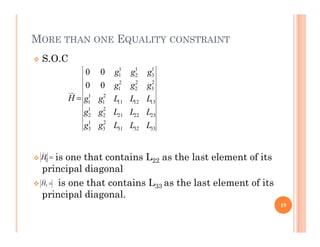

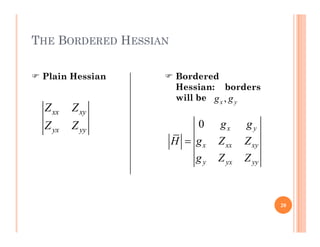

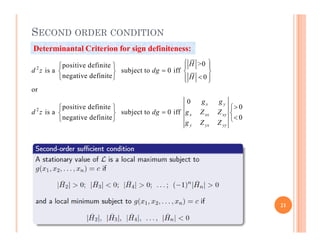

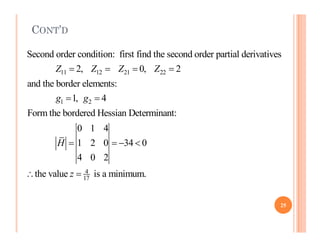

Given a bordered Hessian

Given a bordered Hessian

1 2

1 11 12 1

2 21 22 2

1 2

0 n

n

n

n n n nn

g g g

g Z Z Z

H g Z Z Z

g Z Z Z

26](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter2-240528135328-67fdcfcb/85/Chapter-2-Constrained-Optimization-lecture-note-pdf-26-320.jpg)

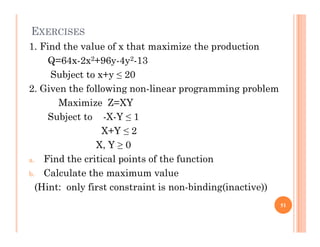

![EXAMPLE: LEAST COST COMBINATION OF INPUTS

K L

C P K P L

0

( , )

Q K L Q

Minimize :

subject to:

First Order Condition:

0

0

[ ( , )]

( , ) 0

0

0

K L

K K K

L L L

K K

L L

Z P K P L Q Q K L

Z Q Q K L

Z P Q

Z P Q

P Q

P Q

First Order Condition:

29](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter2-240528135328-67fdcfcb/85/Chapter-2-Constrained-Optimization-lecture-note-pdf-29-320.jpg)