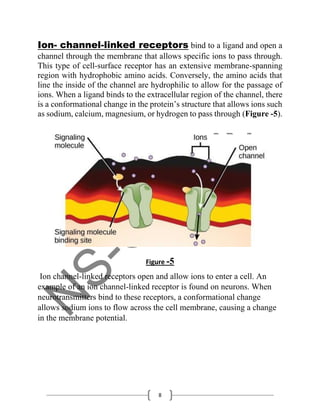

Cell signaling is a crucial process that allows communication between cells to coordinate activities and maintain homeostasis, involving various types of signaling such as autocrine, paracrine, and endocrine. The document details signaling molecules, types of receptors, and signal transduction pathways, emphasizing the role of ligands and receptors in initiating cellular responses and gene expression. It also discusses disruptions in signaling that can lead to diseases like cancer and diabetes, along with the importance of hormones and their specific receptors in regulating physiological processes.