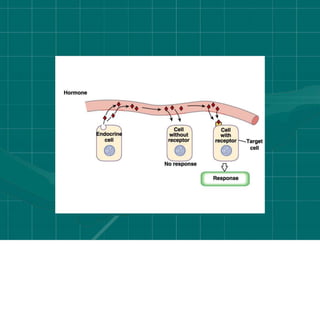

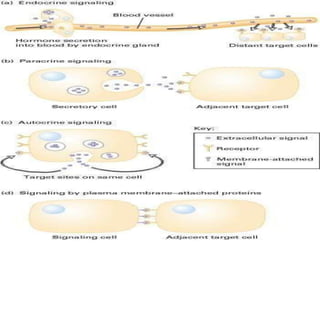

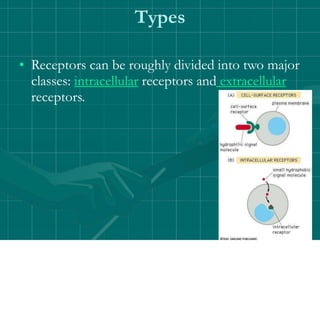

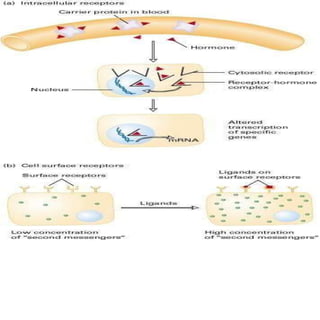

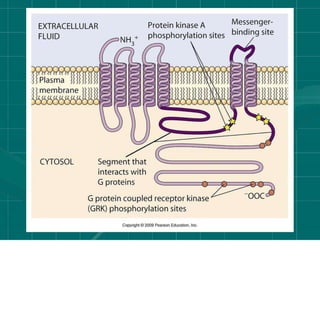

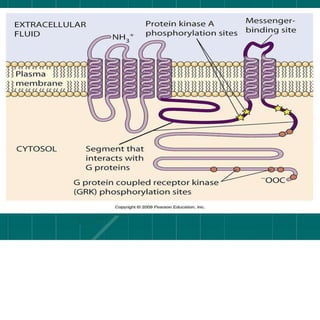

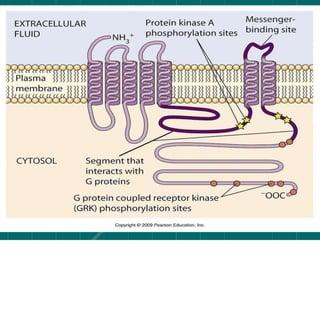

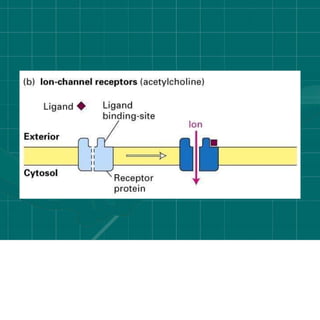

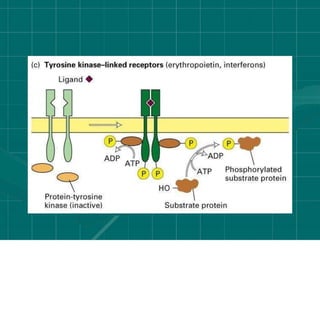

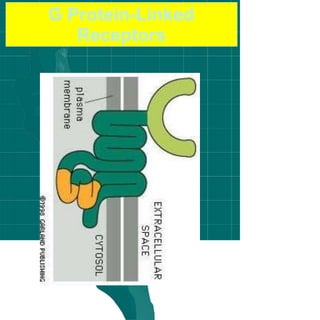

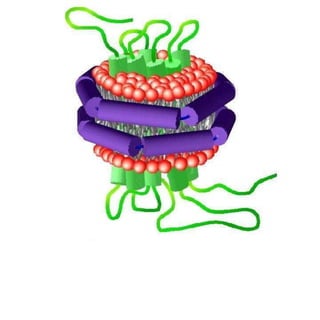

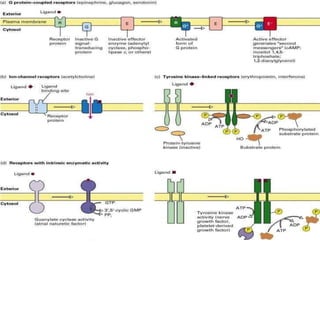

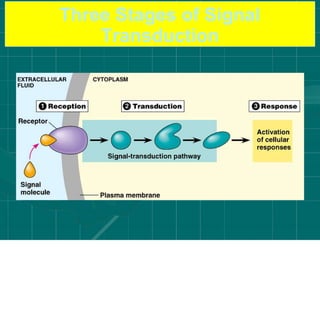

Cellular signaling allows cells to communicate with each other and coordinate functions through signal transduction pathways. Environmental stimuli can initiate these pathways, transmitting signals from one cell to another via extracellular signaling molecules like hormones or direct cell contact. There are several types of cellular receptors that receive these signals, including cell surface receptors which span the membrane and contain extracellular, transmembrane, and intracellular domains to transmit the signal inside the cell. Binding of ligands to different types of receptors can have varied effects through mechanisms like activating intracellular enzymes or changing receptor conformation.