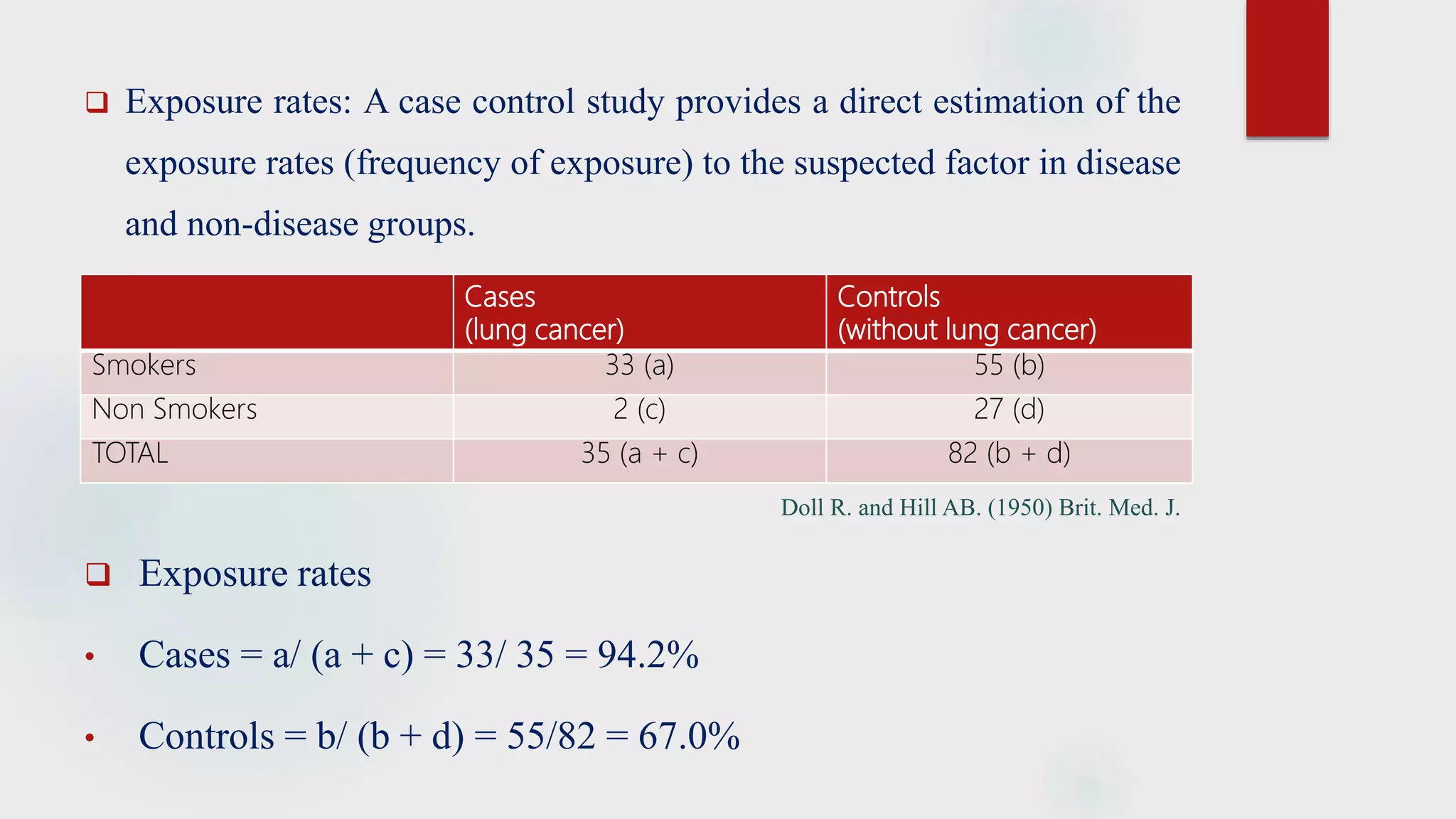

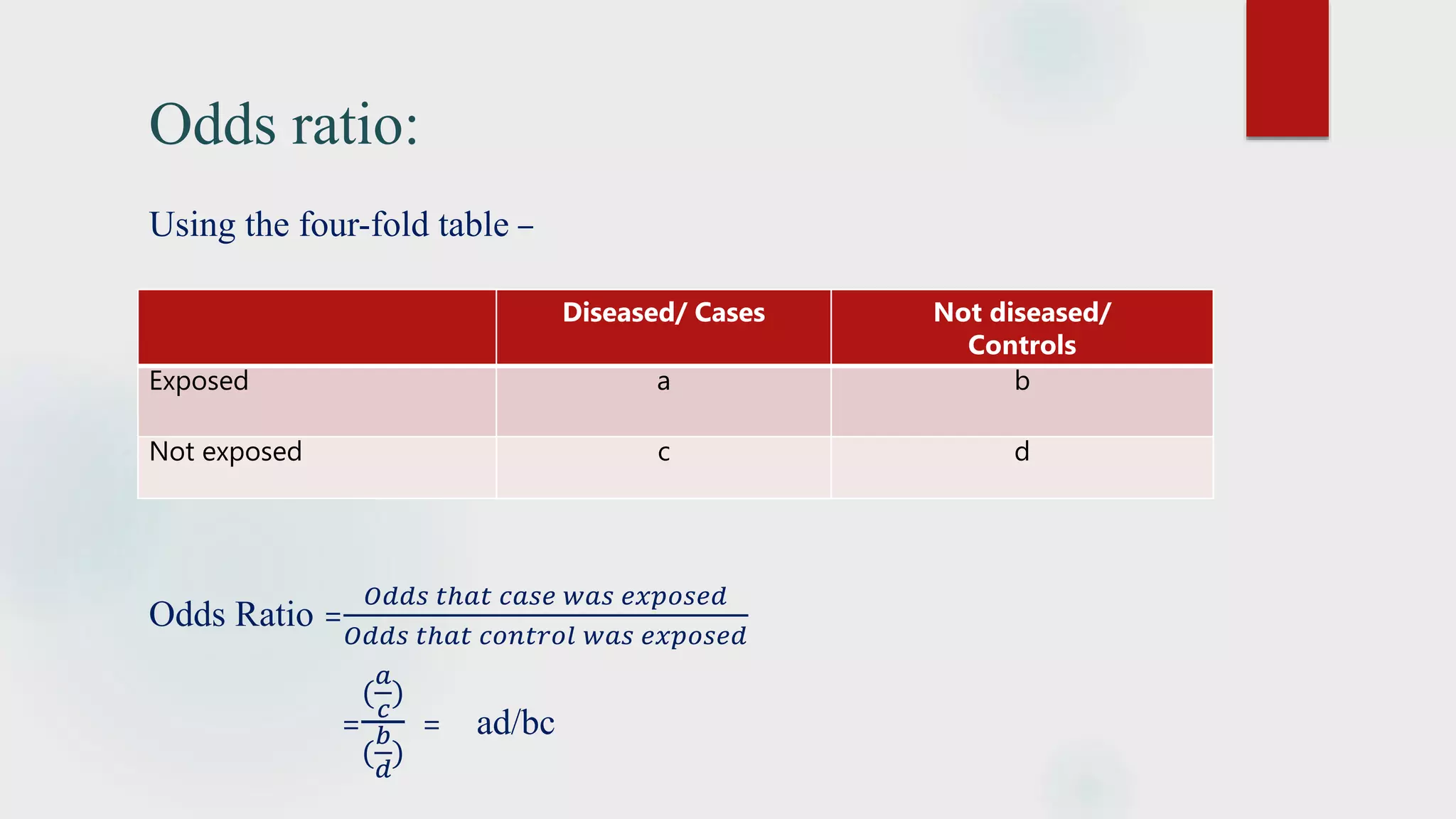

The document discusses the case control study methodology in epidemiology, detailing its history, design, advantages, and limitations. Key components include case selection, control matching, exposure measurement, and the analysis of odds ratios to estimate disease risk. It provides classical examples such as the association of cigarette smoking with lung cancer and oral contraceptives with thromboembolic disease.