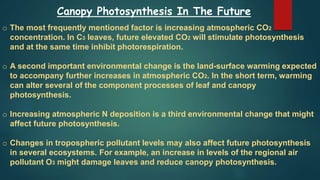

This document discusses factors that affect canopy photosynthesis in plants, including sunlight, leaf architecture, wind, temperature, vapor pressure deficit, leaf nitrogen, water relations, and season. It provides examples of how each factor influences the rate of photosynthesis at the canopy level, such as erect leaves allowing higher photosynthetic rates than horizontal leaves, and soil moisture deficits reducing photosynthesis through effects on stomatal conductance. The document also discusses seasonal variations in canopy photosynthesis and models predictions for how rising CO2, warming temperatures, and other environmental changes may impact future photosynthesis.

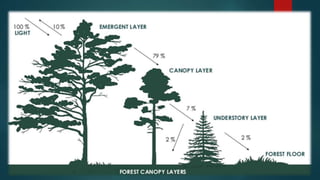

![Photosynthetic rates of plant systems vary over

the course of the growing season as

photosynthetic capacity, the availability of solar

radiation & soil moisture, & air & soil temp. vary.

Leaf form (needle, broadleaf), leaf habit (evergreen, deciduous),

and latitude also affect the seasonal pattern of CO 2 exchange.

It shows that broadleaved forest canopies lose carbon when the

canopy is dormant.

During springtime leaf expansion the direction and magnitude of

carbon fluxes switch rapidly as forests change from losing 1-3 g C

m -2 d-1 ] to gaining 5-10 g C m -2 d-1.

h) Season](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/09abt15pp-170612181922/85/CANOPY-PHOTOSYNTHESIS-FACTOR-AFFECTING-PHOTOSYNTHESIS-16-320.jpg)