The document discusses the role of managed forests in carbon sequestration amidst rising atmospheric CO2 levels, highlighting how forest management practices can enhance tree growth and overall forest health. It emphasizes the potential benefits and challenges of increased CO2 concentrations on forest productivity, nutrient cycling, and water use, while providing management strategies for optimizing carbon storage. Furthermore, the research suggests that effective forest management can significantly contribute to mitigating CO2 emissions through sustainable practices.

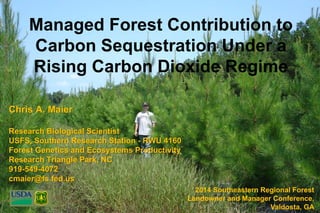

![Photosynthesis: “CO2 fertilization effect"

6CO2 + 6H2O + energy C6H12O6 + 6O2

Pinus taeda

Eucalyptus benthamii

0 200 400 600 800 1000 1200 1400 1600 1800 2000

[CO2] (ppm)

Net Photosynthesis ( mol m-2s-1)

40

30

20

10

0

• Photosynthesis increases with CO2

• 30-50% at 550 ppm

• Elevated CO2 decreases stomatal conductance

and increases water use efficiency

sugar](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/maiersrflmconfoct2014-141111142330-conversion-gate01/85/Managed-forest-contribution-to-carbon-sequestration-under-a-rising-carbon-dioxide-regime-Chris-Maier-Research-Biological-Scientist-USFS-Southern-Research-Station-RWU-4160-Forest-Genetics-and-Ecosystems-Productivity-14-320.jpg)