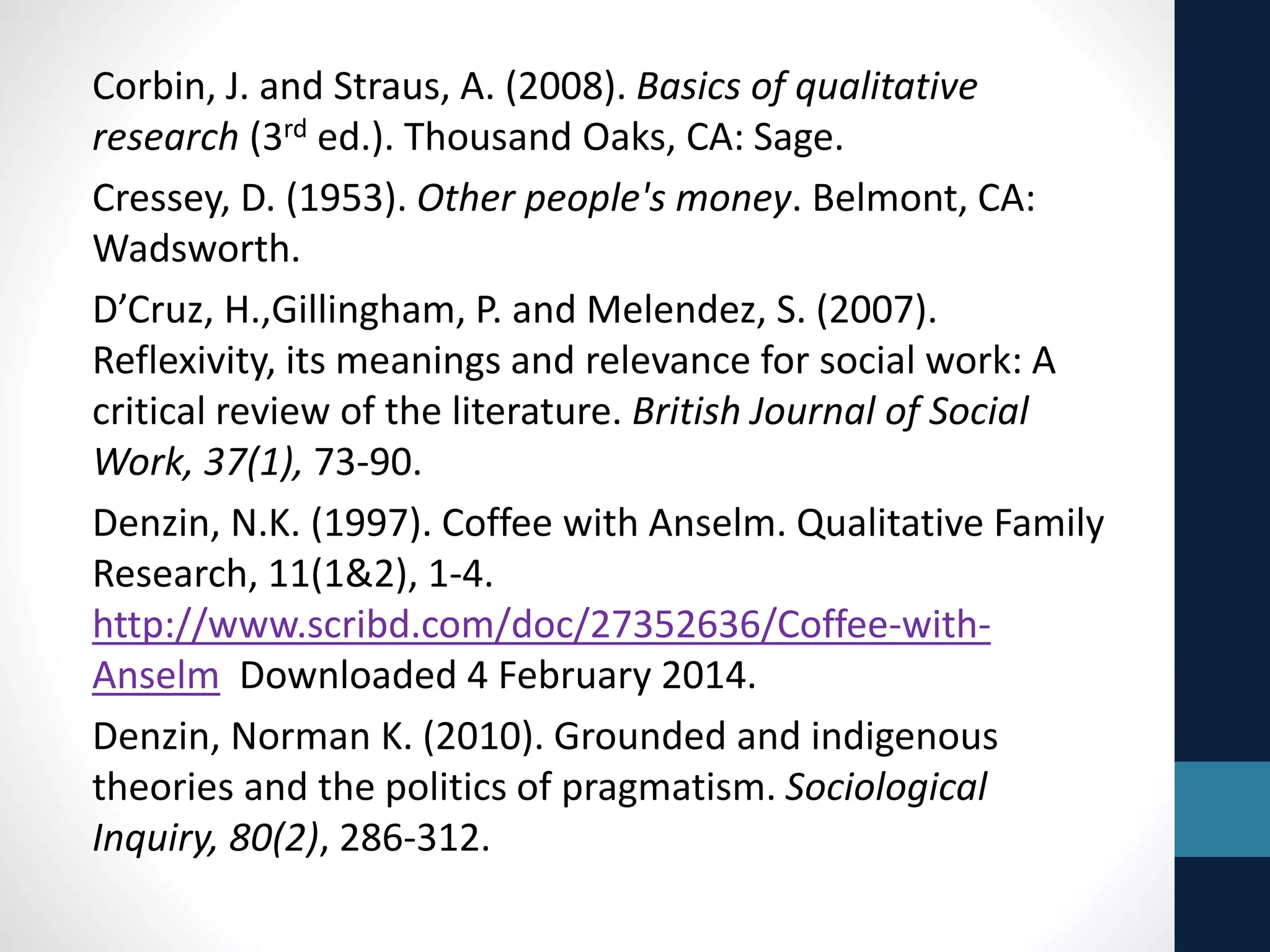

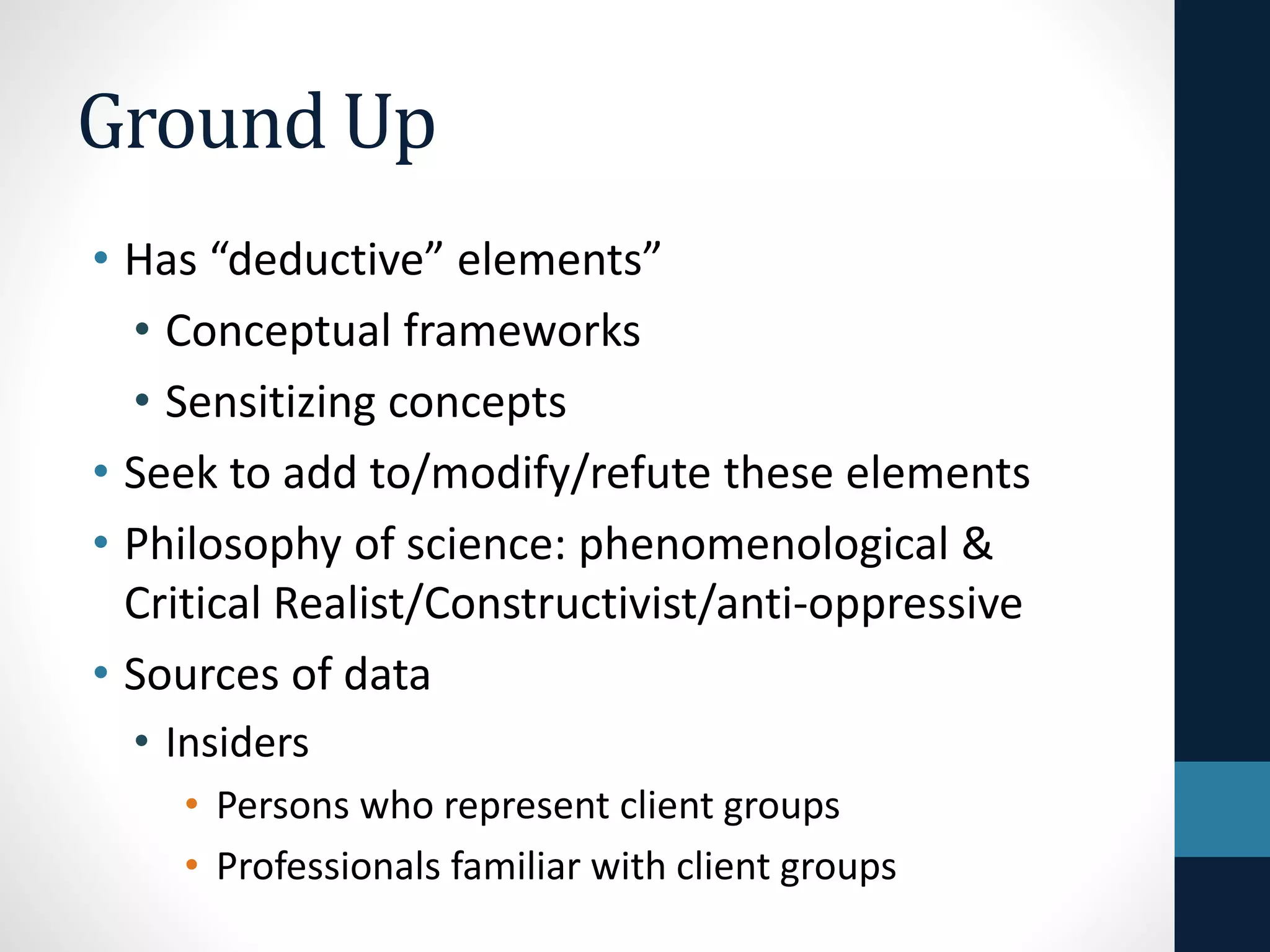

The document focuses on building models of social processes in social work, emphasizing two approaches: top-down and ground-up models. It discusses the importance of theories and models in understanding relationships and guiding research, highlighting key elements such as emotional expressiveness and factors affecting outcomes in complex trauma. The paper also addresses the role of evidence-based practice and proposes interventions with perpetrators of violence, emphasizing the necessity of understanding participant perspectives and ethical considerations in social work research.

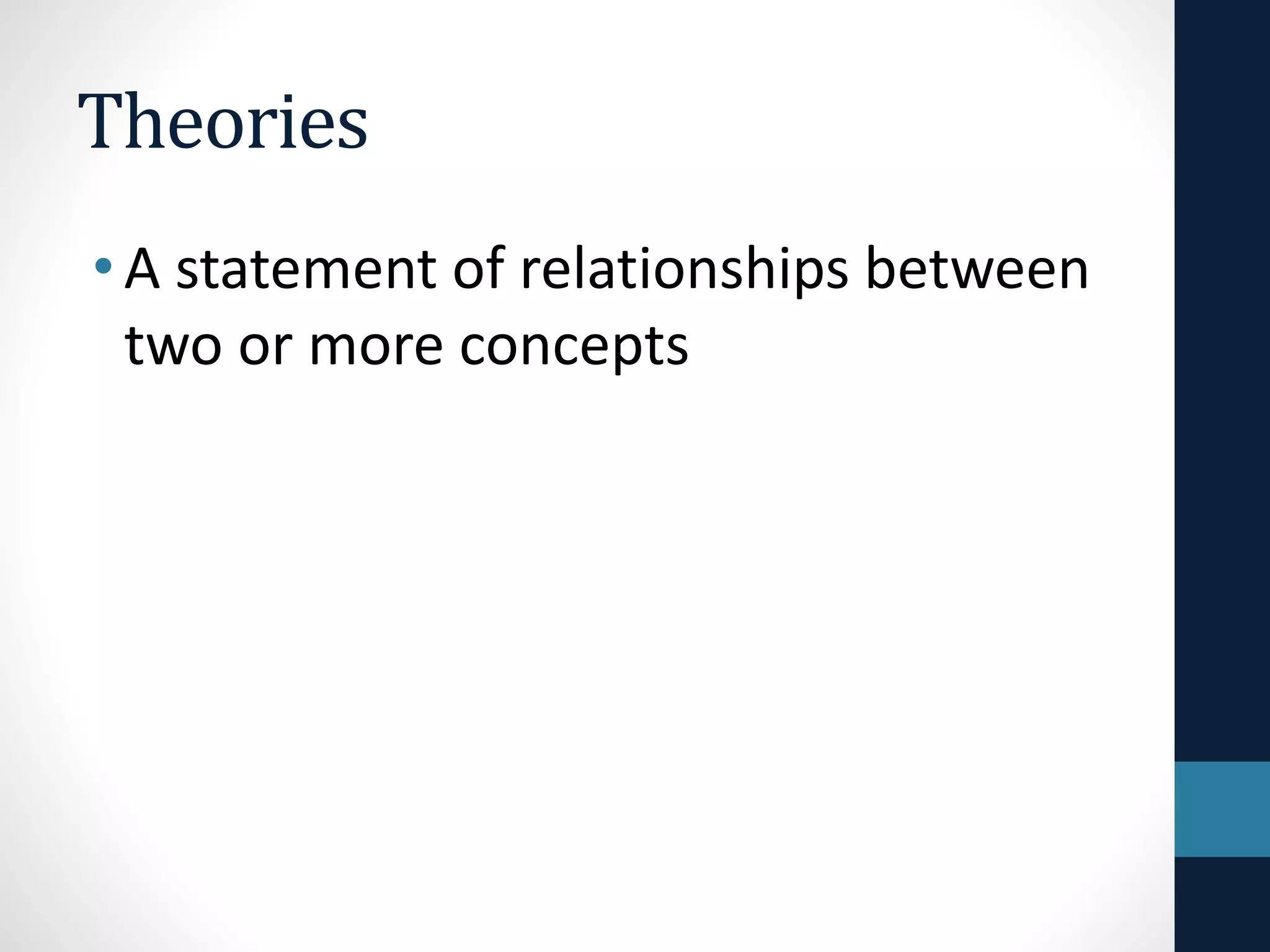

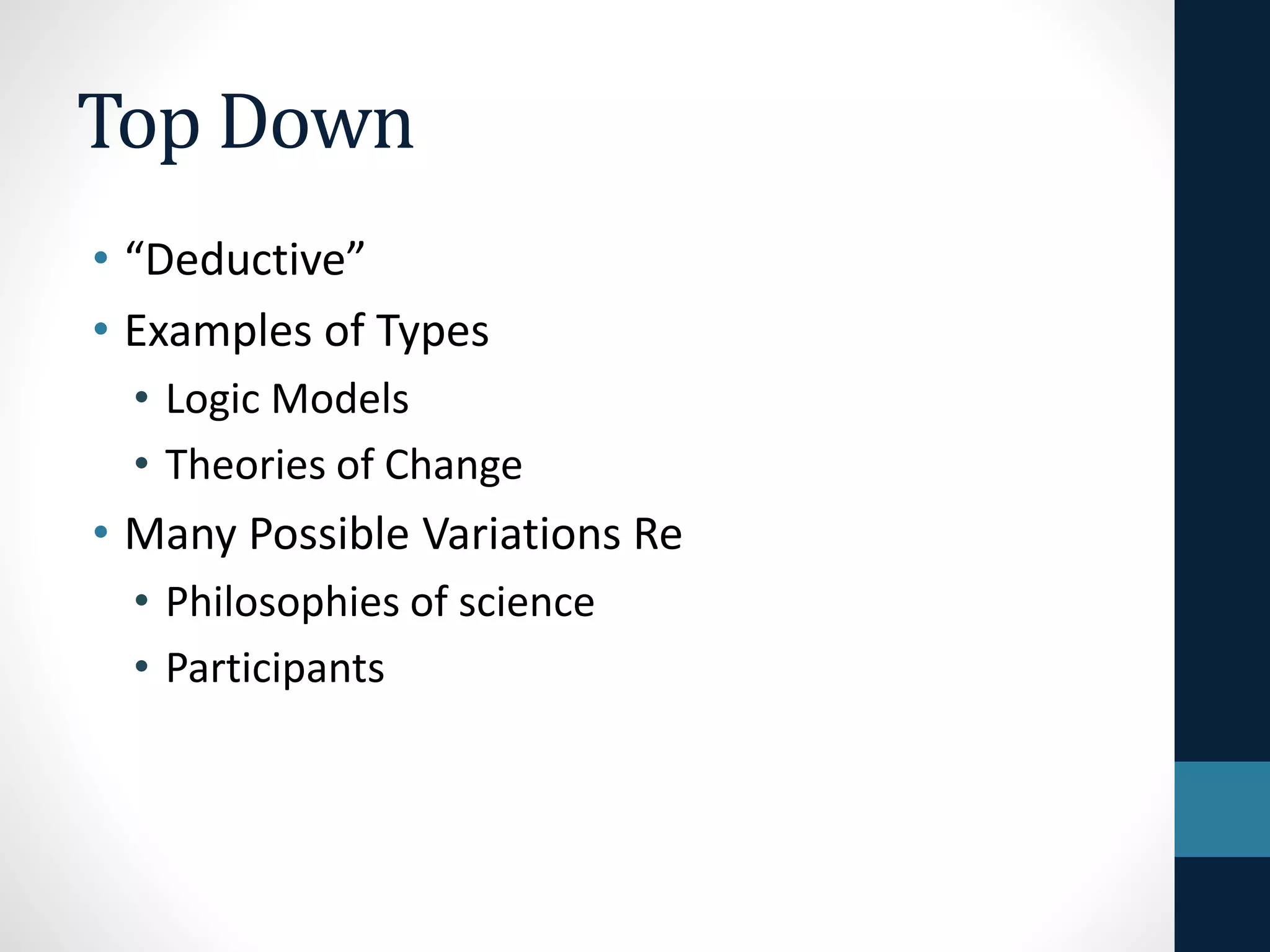

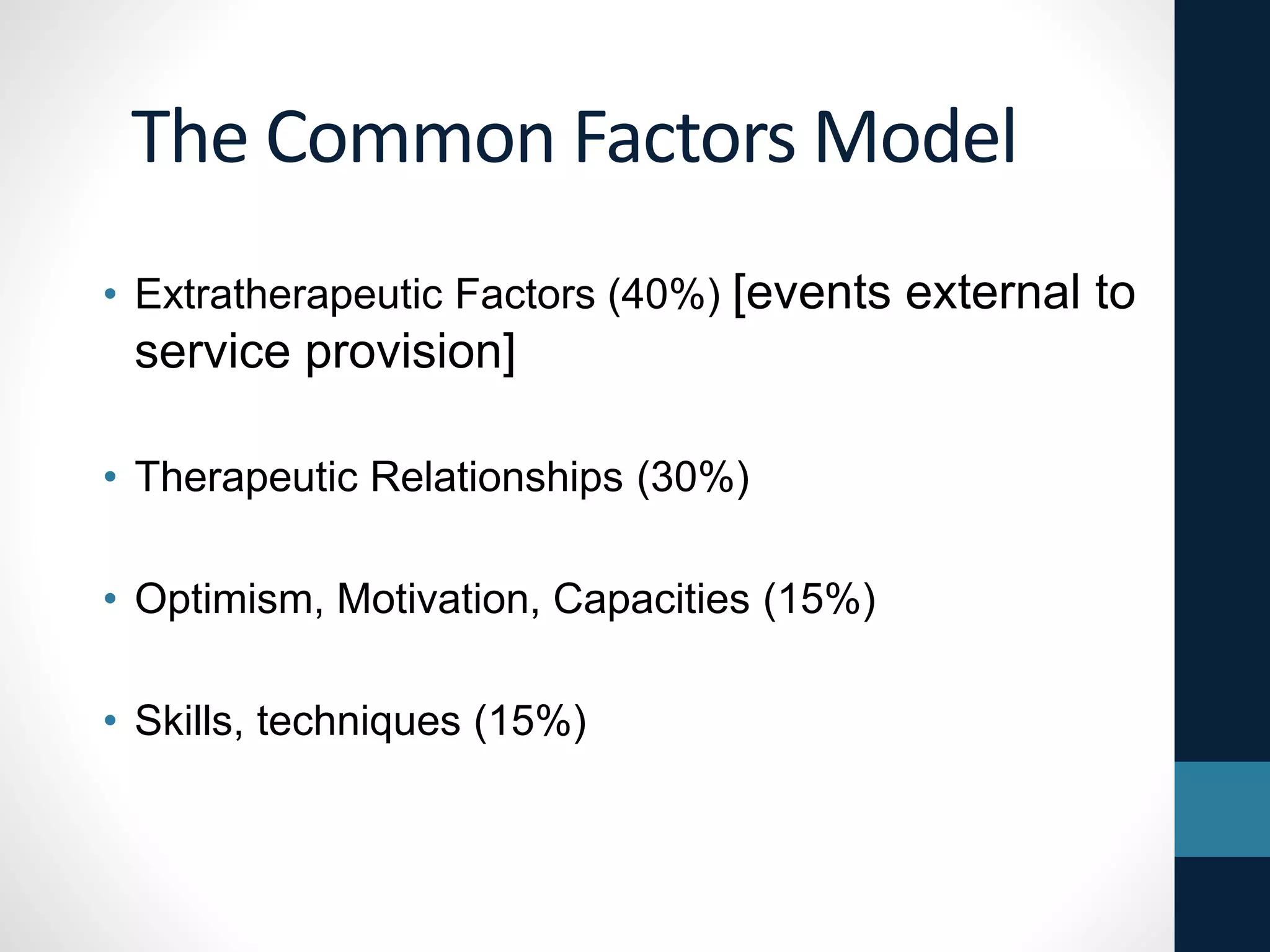

![The Common Factors Model

• Extratherapeutic Factors (40%) [events external to

service provision]

• Therapeutic Relationships (30%)

• Optimism, Motivation, Capacities (15%)

• Skills, techniques (15%)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/buildingmodels-141008103933-conversion-gate01/75/Building-Models-of-Social-Processes-from-the-Ground-Up-Two-Case-Studies-26-2048.jpg)