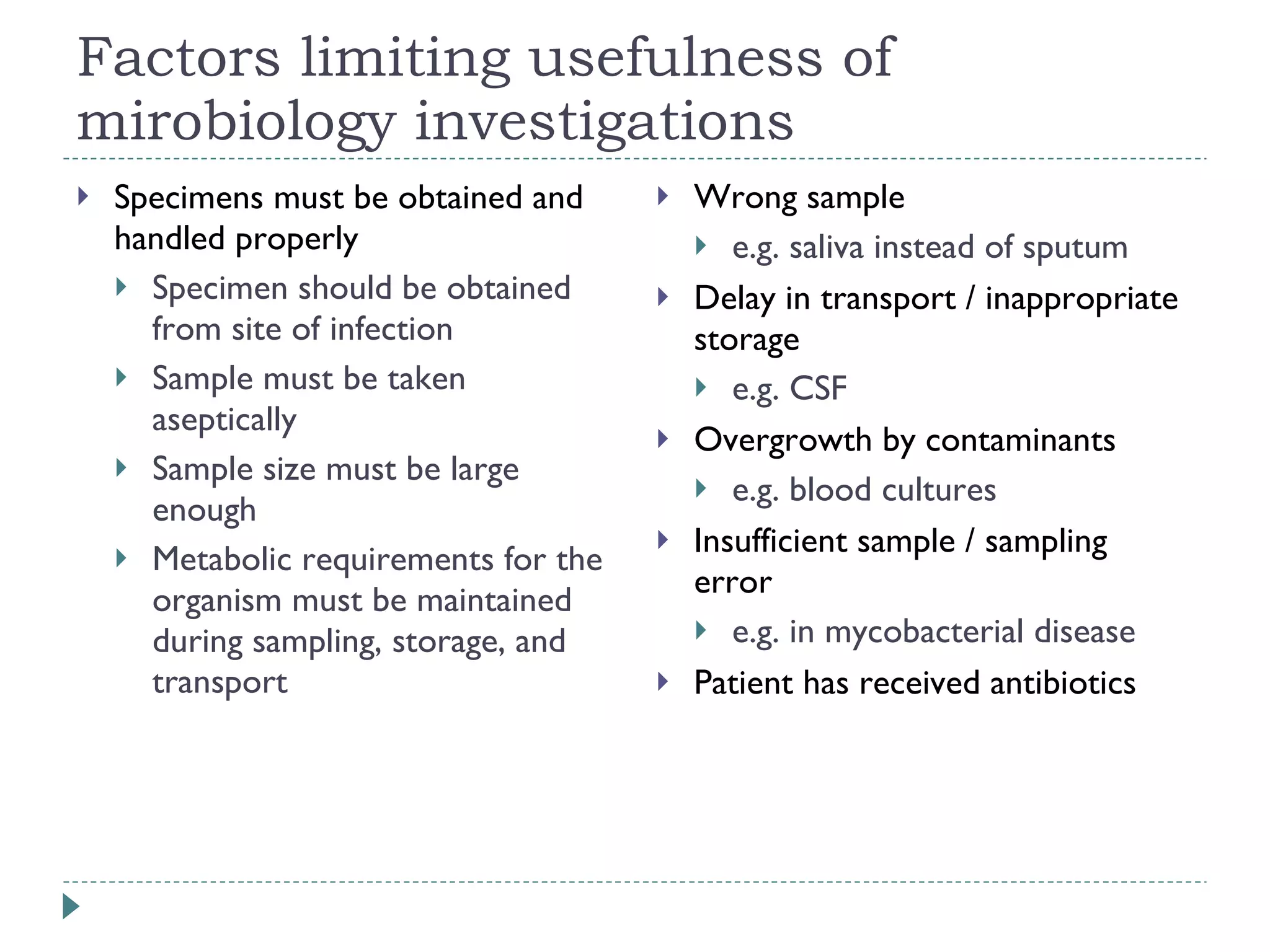

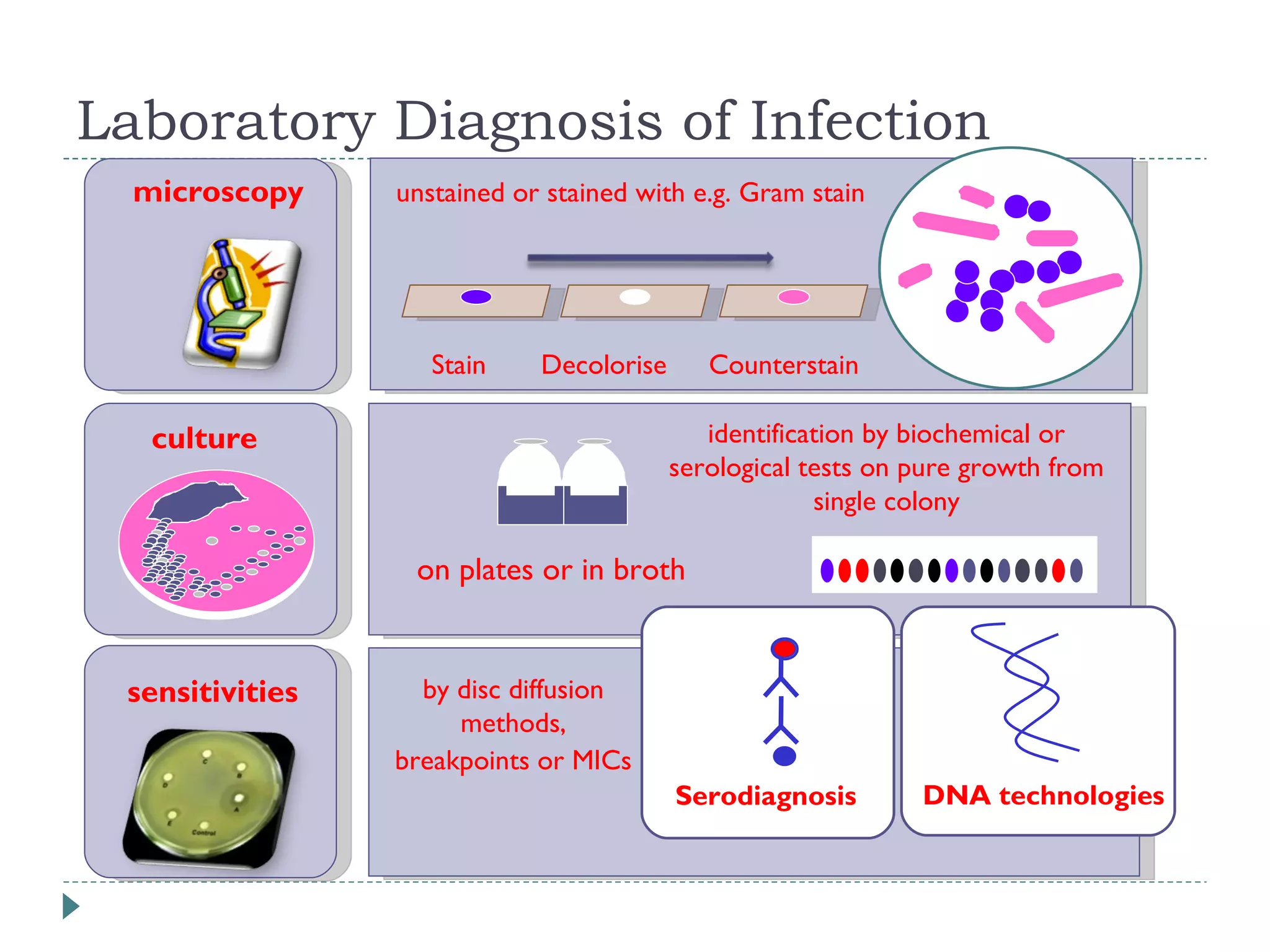

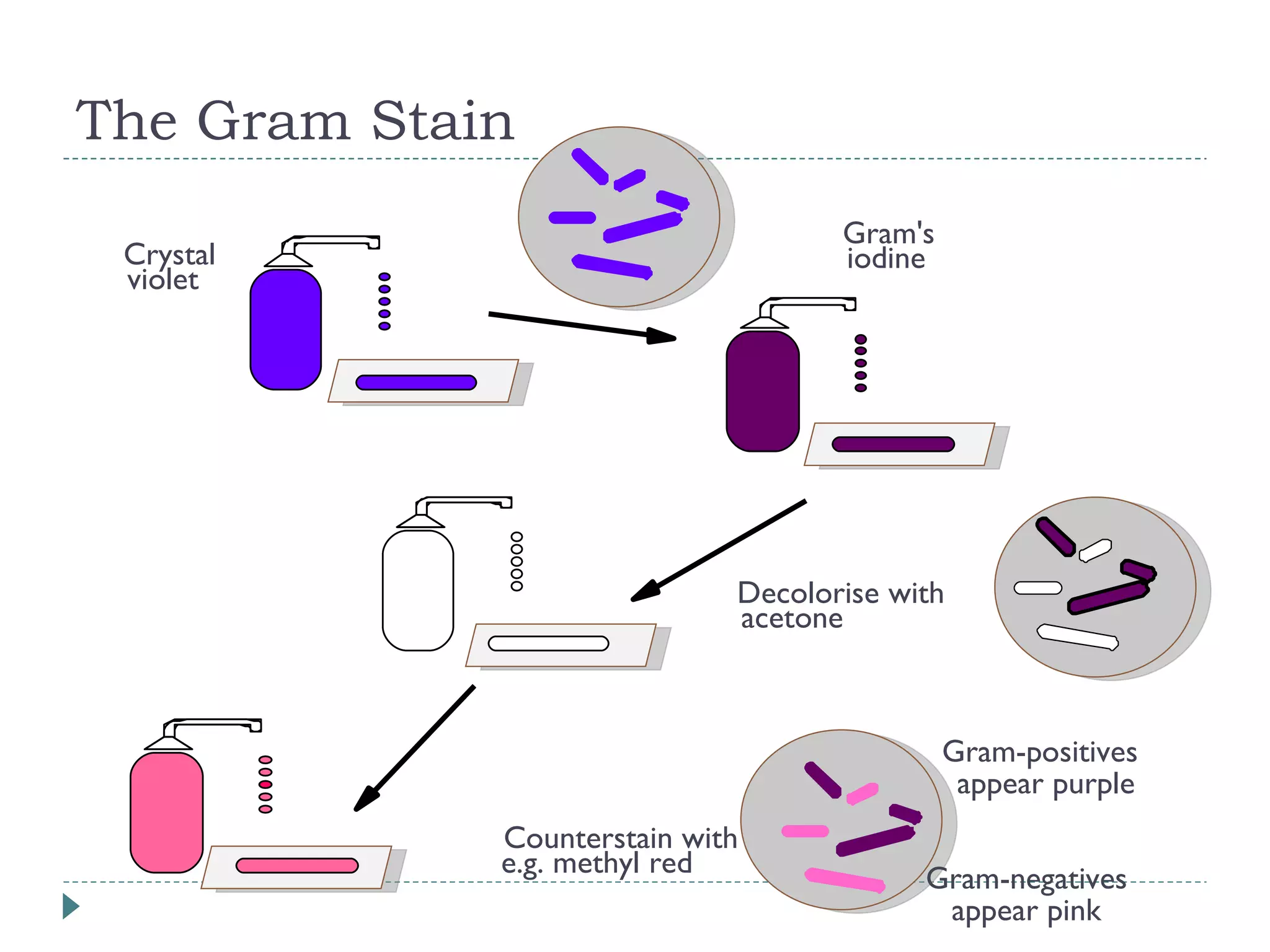

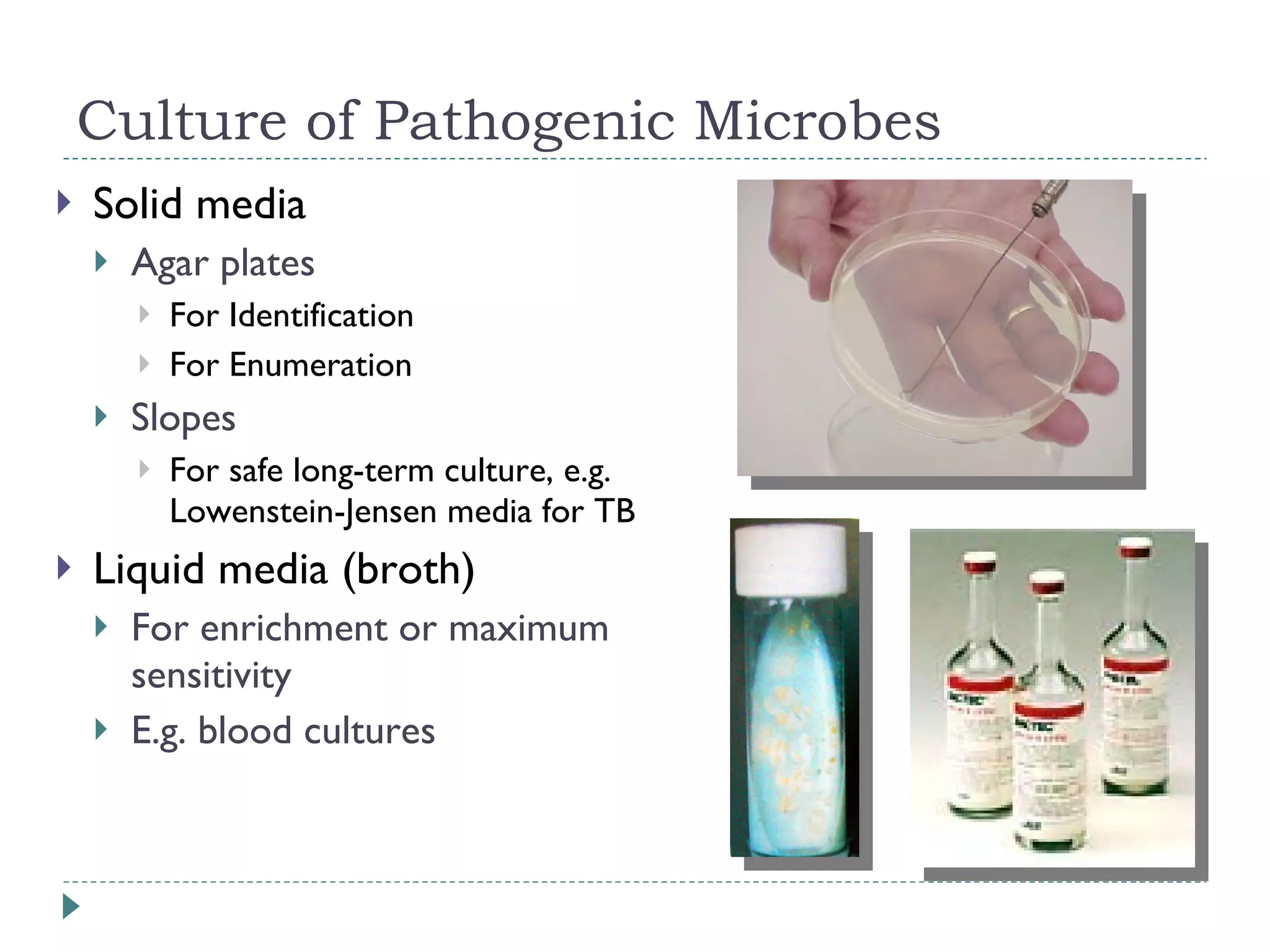

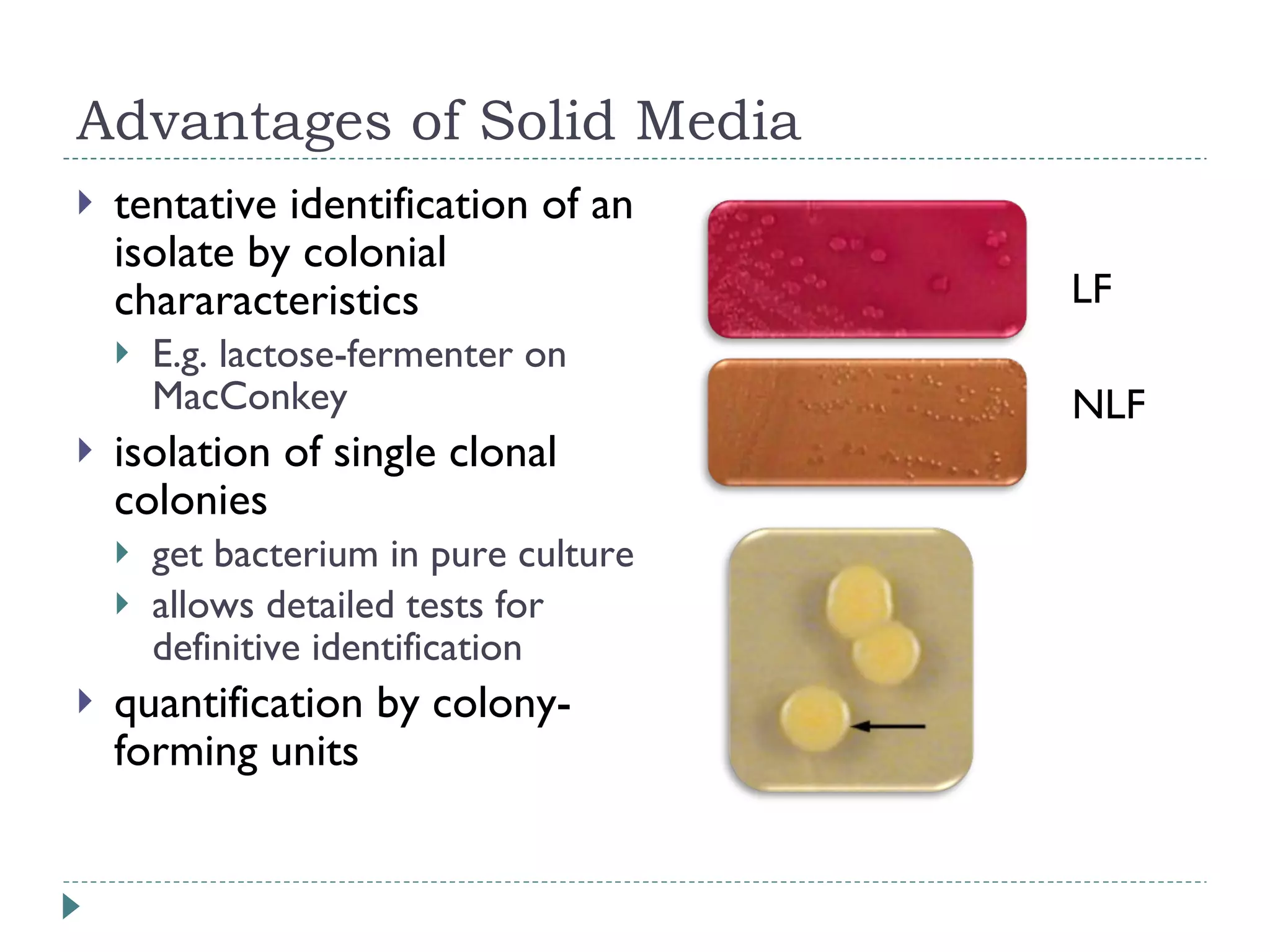

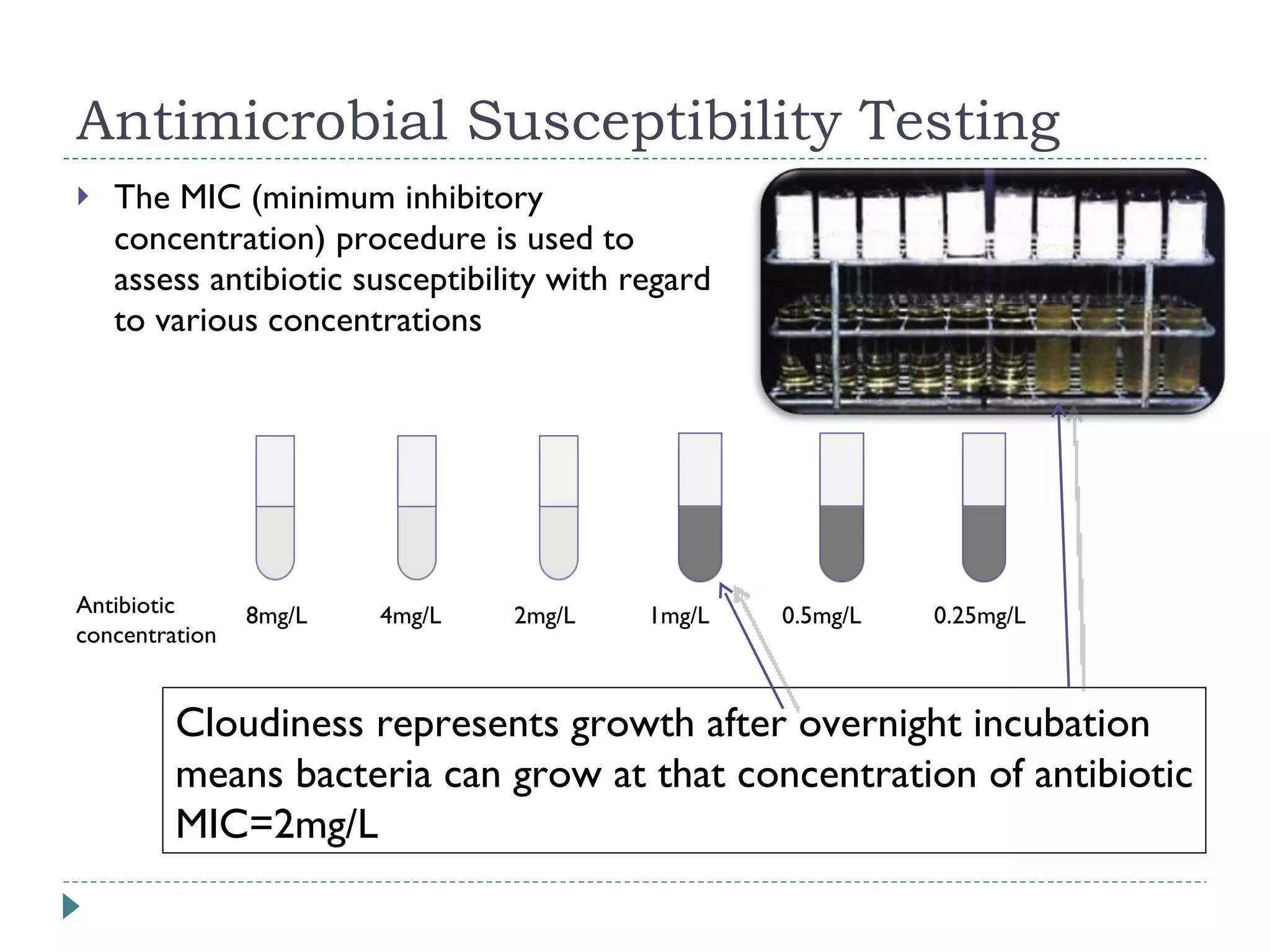

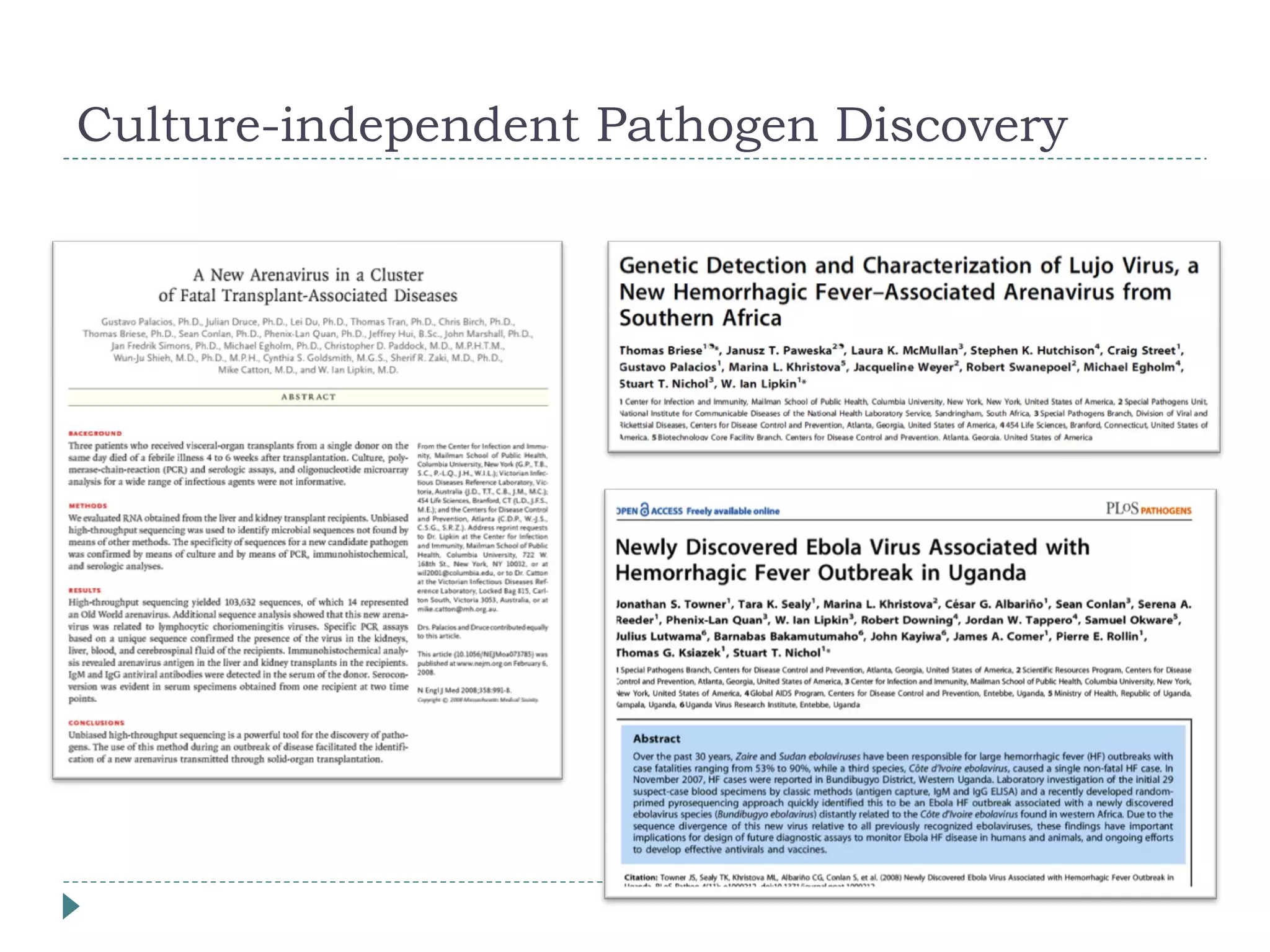

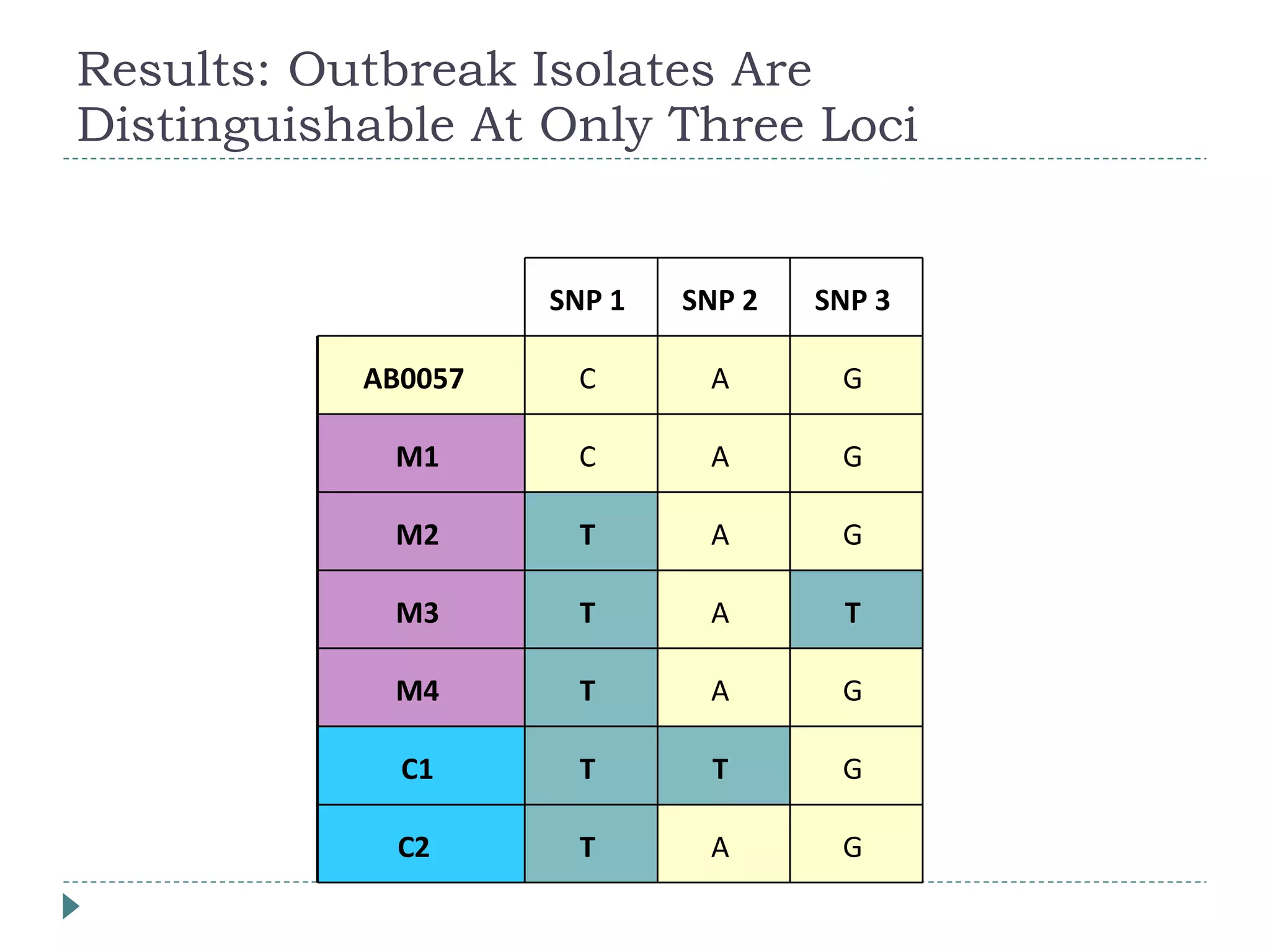

The document discusses laboratory diagnosis methods for infectious diseases, detailing techniques such as microscopy, culture, immunological tests, and high-throughput sequencing. It emphasizes the importance of proper sample collection and handling to ensure accurate diagnoses while outlining various microbiological and molecular methods for identifying pathogens. Additionally, it highlights the advancements in genomic epidemiology, especially in understanding and tracking multi-drug resistant infections.