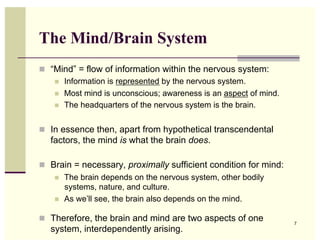

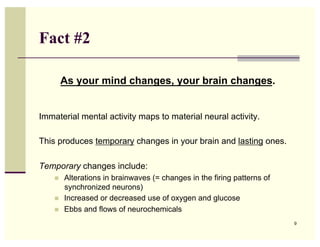

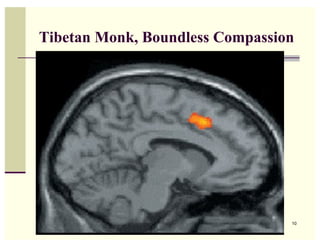

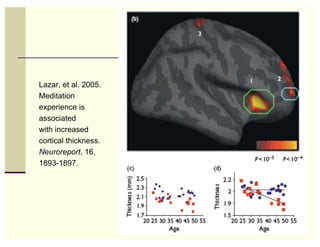

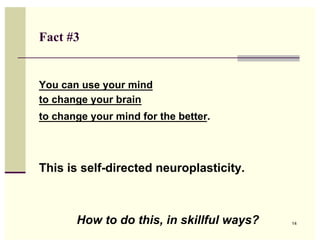

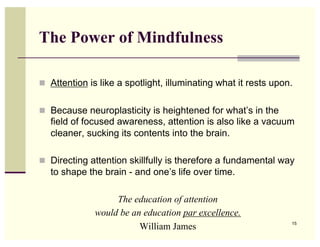

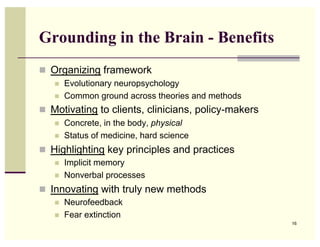

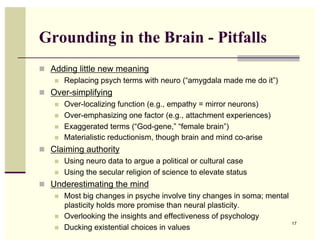

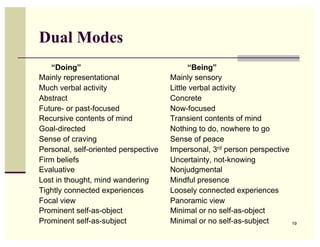

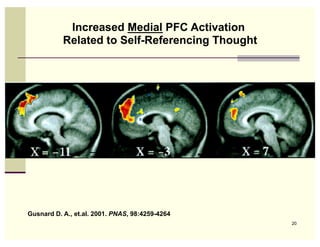

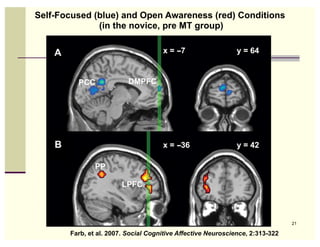

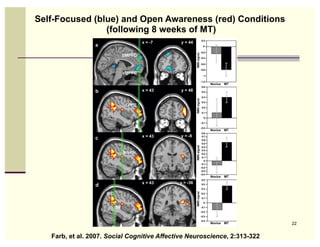

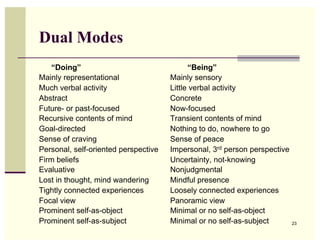

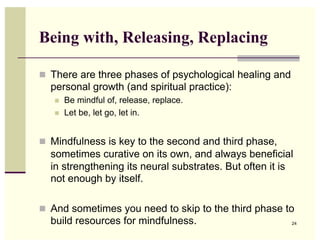

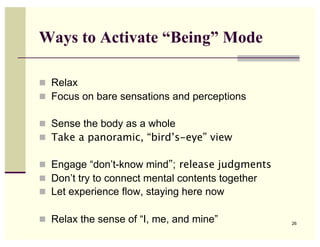

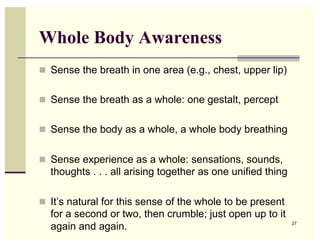

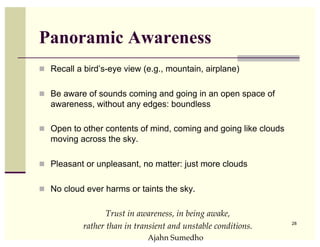

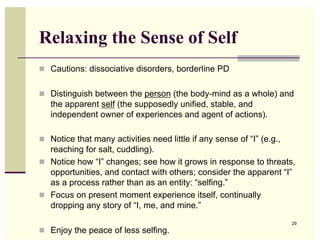

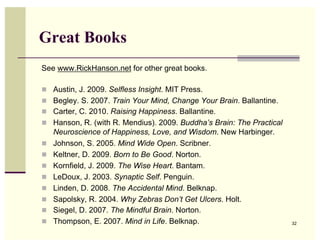

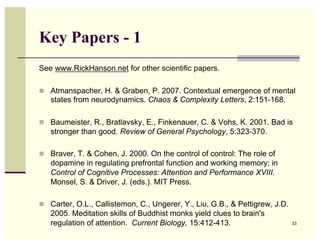

The document discusses the relationship between the brain and mind, emphasizing self-directed neuroplasticity and how mindfulness can facilitate changes in both. It contrasts 'doing' and 'being' modes of mental activity, highlighting their impacts on psychological healing and personal growth. Furthermore, it provides strategies for activating 'being' mode and enhancing mindfulness to promote well-being.