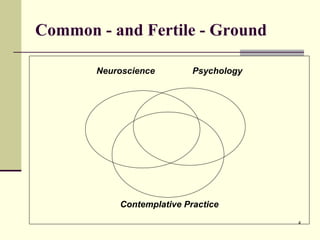

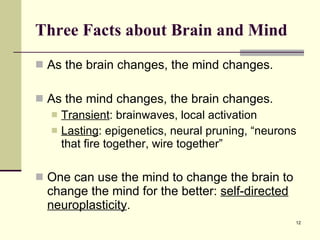

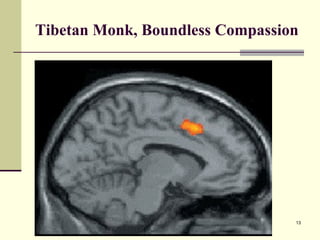

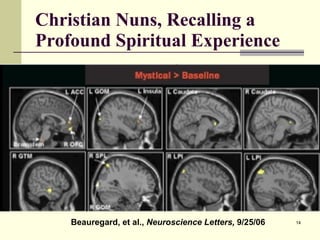

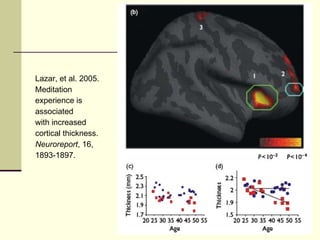

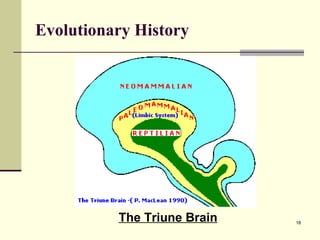

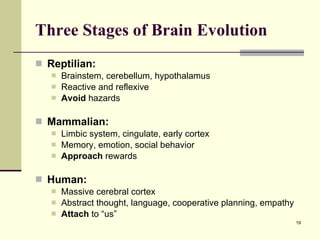

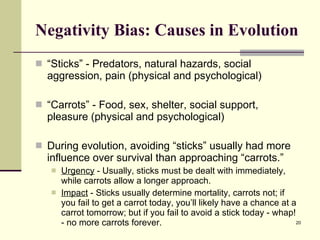

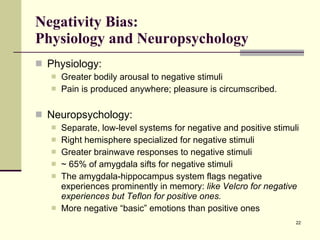

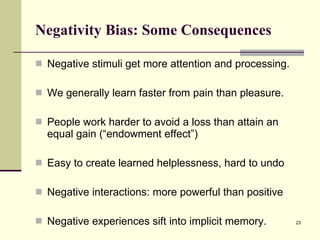

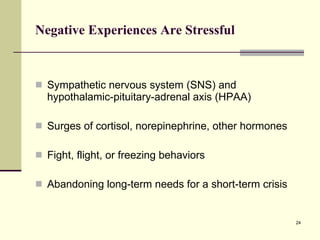

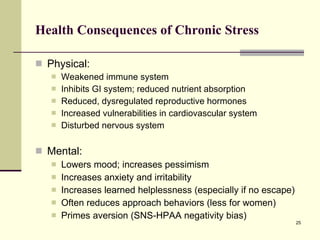

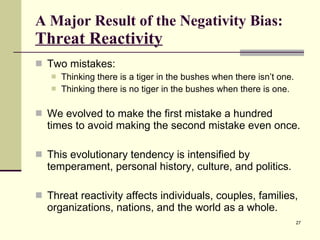

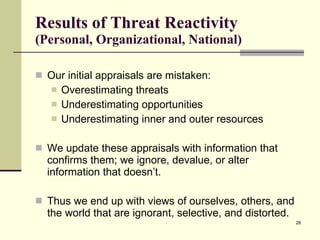

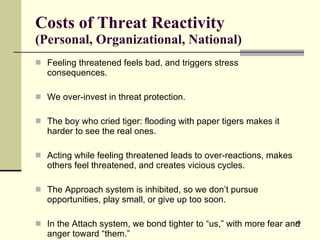

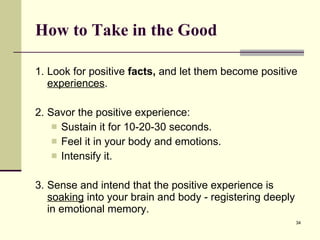

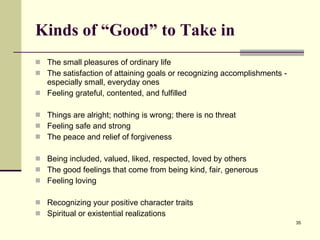

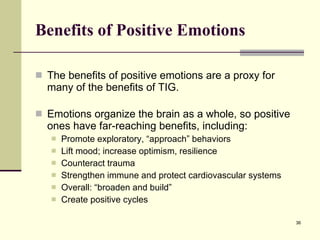

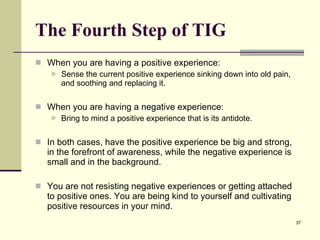

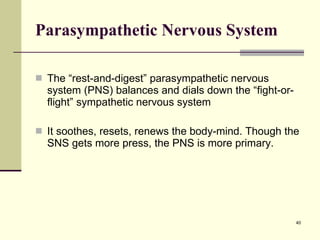

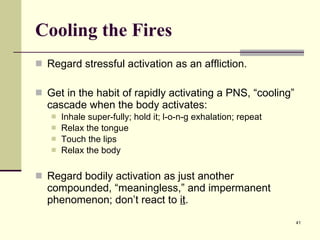

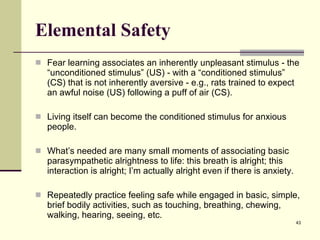

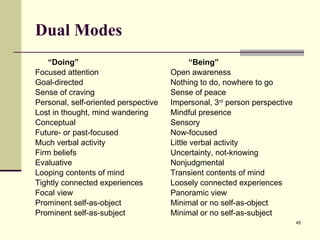

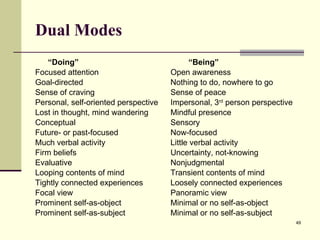

The document discusses the interdependence of brain and mind, emphasizing self-directed neuroplasticity and the evolution of fear and negativity bias shaped by survival instincts. It highlights how negative experiences are remembered more vividly than positive ones, resulting in stress and threat reactivity that can inhibit personal and societal growth. The author advocates for actively engaging with positive experiences to change brain structure and function for improved mental well-being.

![Paper Tiger Paranoia Networker Symposium March 25, 2011 Rick Hanson, Ph.D. The Wellspring Institute for Neuroscience and Contemplative Wisdom www.WiseBrain.org www.RickHanson.net [email_address]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/papertigersrmc2011-110921150629-phpapp01/75/Paper-Tiger-Paranoia-Rick-Hanson-PhD-1-2048.jpg)