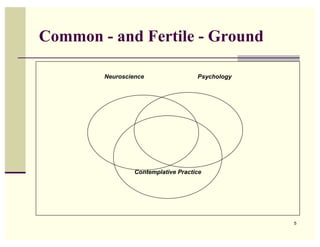

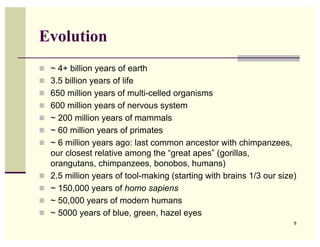

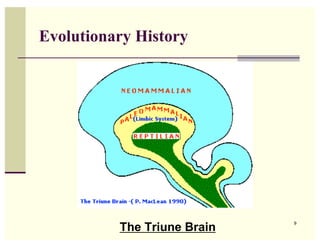

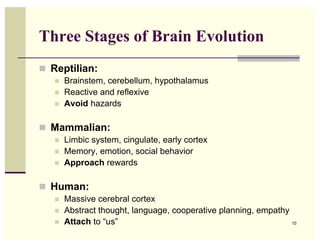

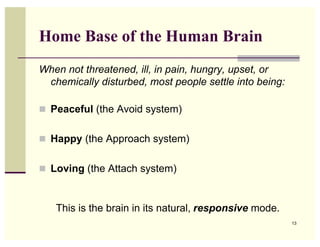

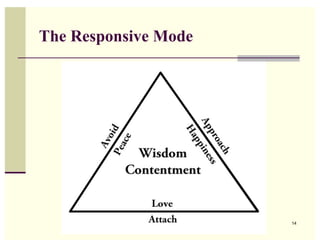

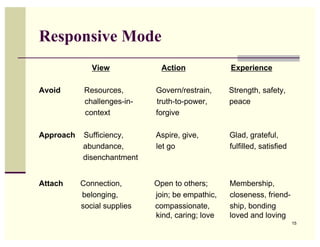

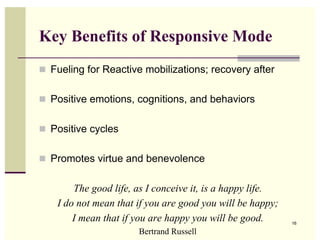

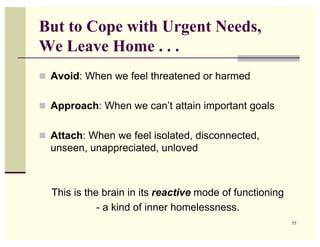

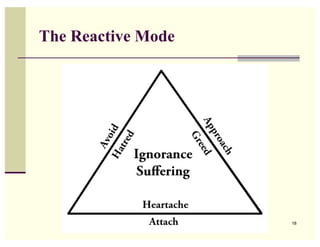

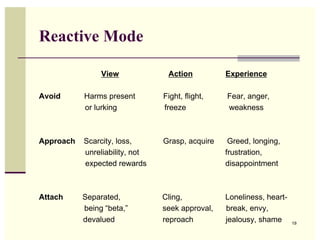

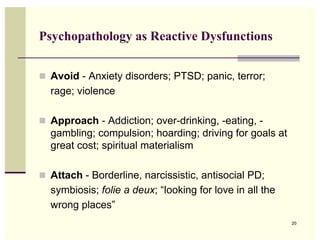

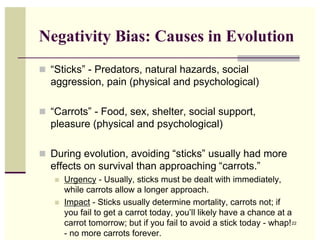

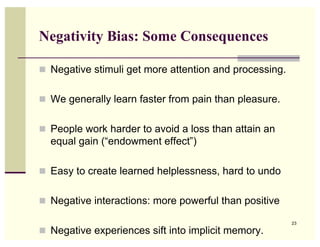

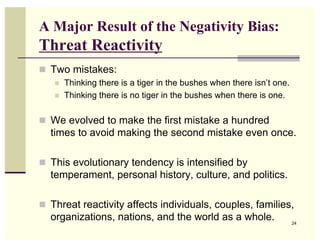

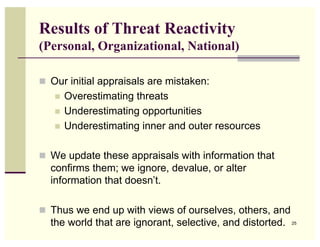

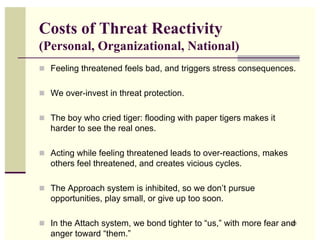

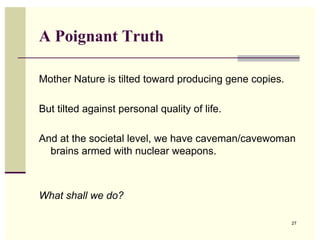

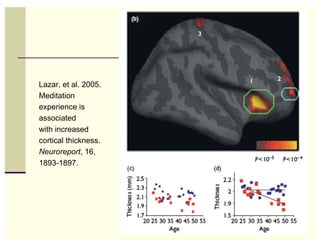

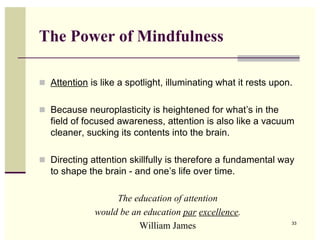

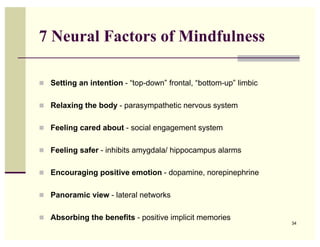

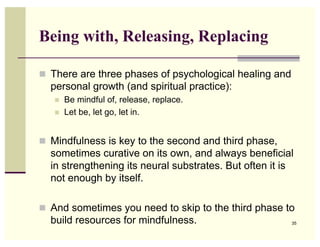

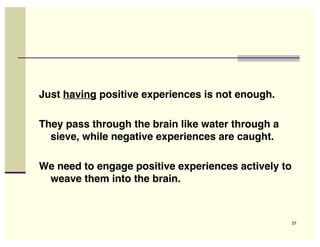

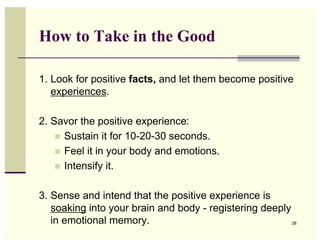

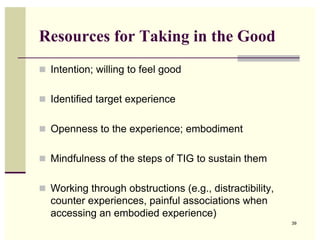

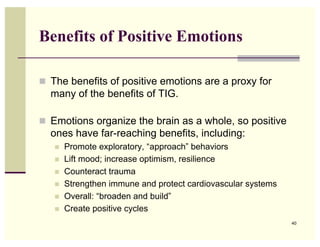

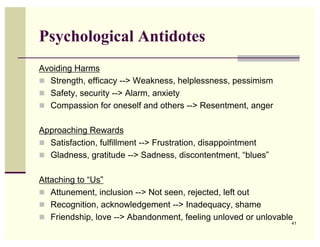

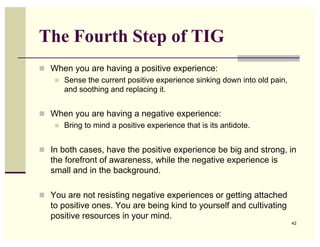

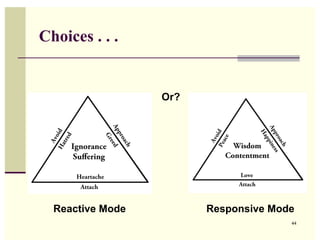

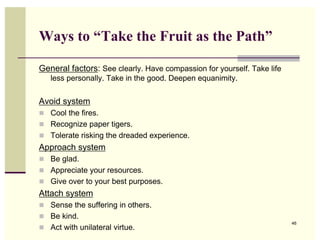

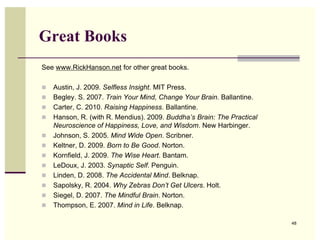

This document summarizes a talk on managing the caveman/cavewoman brain in the 21st century. It discusses perspectives on bringing together neuroscience, psychology and contemplative practice. It then covers topics like the evolving brain, the negativity bias, self-directed neuroplasticity, and coming home to the brain's natural responsive mode. It emphasizes how mindfulness can be used to shape the brain through attention and experience positive emotions and internalize resources in implicit memory. The talk provides strategies for taking in the good and using psychological antidotes to reactive tendencies.