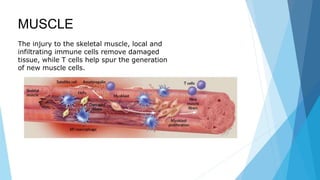

The document discusses behavioral immunology and the bidirectional relationship between behavior and the immune system. It provides examples of how the immune system interacts with behavior in swordfish, electric eels, and sex differences in immune response. The thymus is described as an organ that helps develop T-cells. The behavioral immune system can influence prejudices and disease avoidance behaviors in humans.

![Electric eel

A researcher documents electric eels jumping out of the water to shock potential

threats, confirming a centuries-old report of the defensive behavior.

The electric eel has three pairs of abdominal organs that produce electricity: the

main organ, the Hunter's organ, and the Sach's organ. These organs make up four-

fifths of its body, and give the electric eel the ability to generate two types of

electric organ discharges: low voltage and high voltage. These organs are made of

electrocytes, lined up so a current of ions can flow through them and stacked so

each one adds to a potential difference.[citation needed]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/naseebpresentation-191206095825/85/Behavioral-immunology-5-320.jpg)

![ When the eel finds its prey, the brain sends a signal through the nervous

system to the electrocytes.[citation needed] This opens the ion channels, allowing

sodium to flow through, reversing the polarity momentarily. By causing a

sudden difference in electric potential, it generates an electric current in a

manner similar to a battery, in which stacked plates each produce an electric

potential difference.

In the electric eel, some 5,000 to 6,000 stacked electroplaques are can make

a shock up to 860 volts and 1 ampere of current (860 watts) for two

milliseconds. Such a shock is extremely unlikely to be deadly for an adult

human, due to the very short duration of the discharge.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/naseebpresentation-191206095825/85/Behavioral-immunology-6-320.jpg)