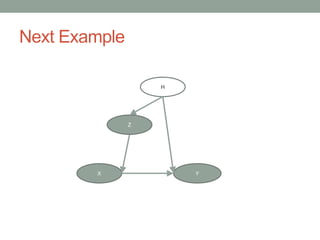

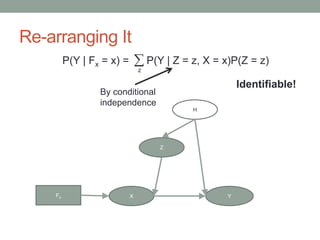

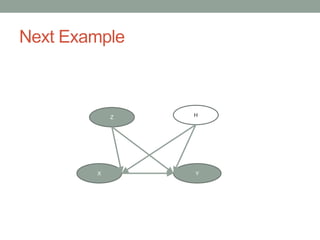

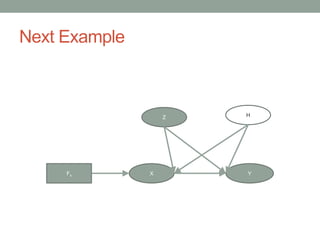

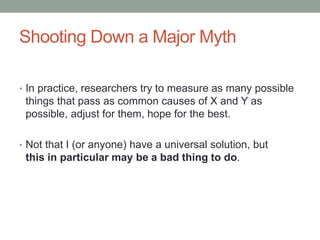

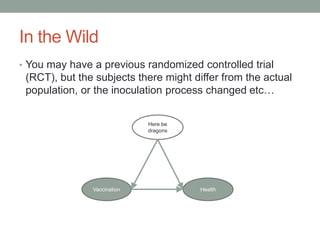

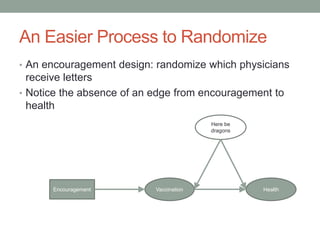

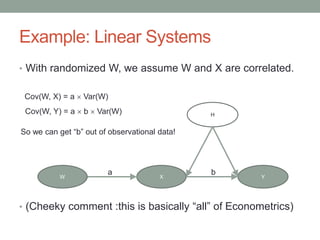

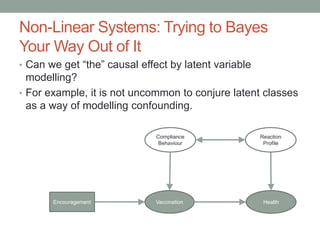

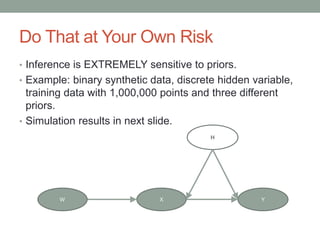

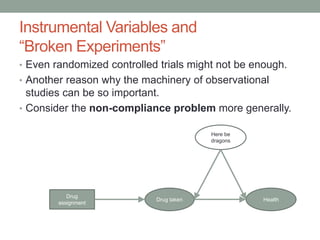

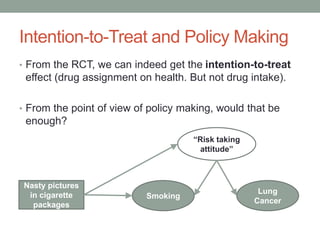

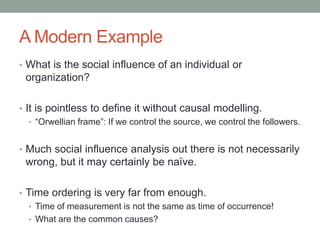

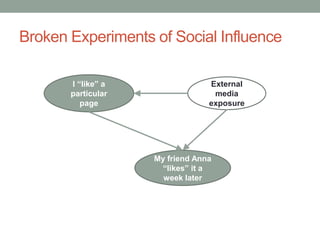

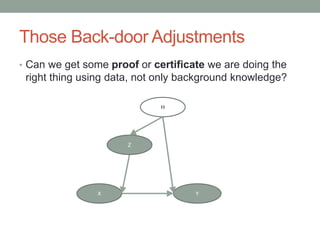

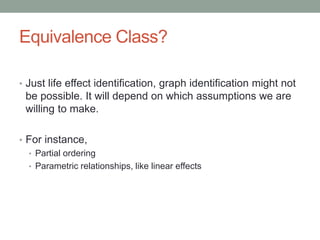

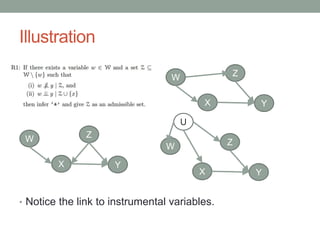

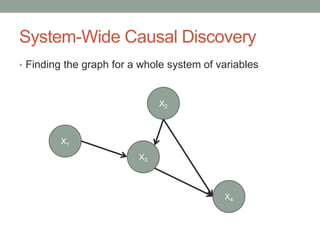

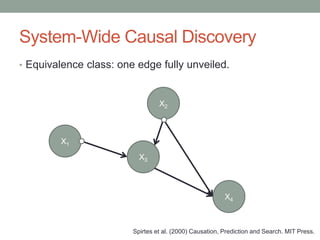

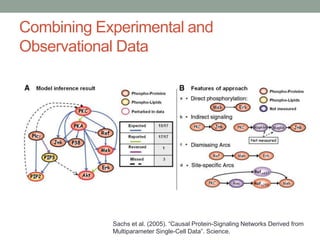

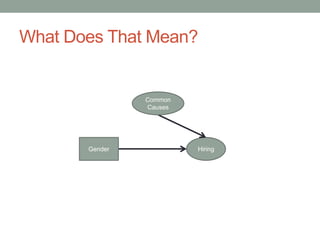

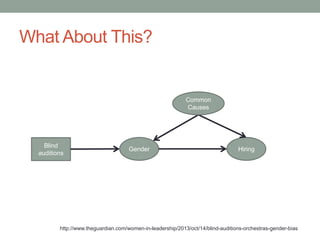

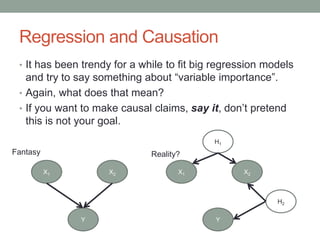

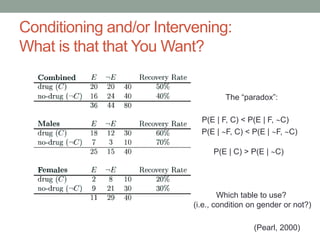

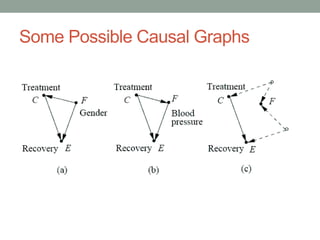

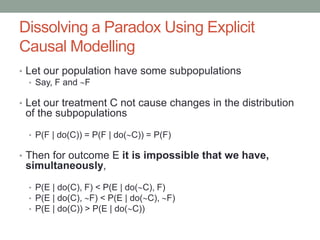

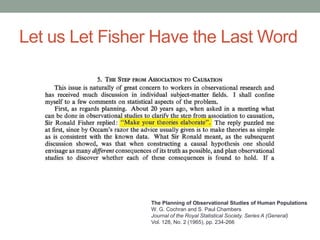

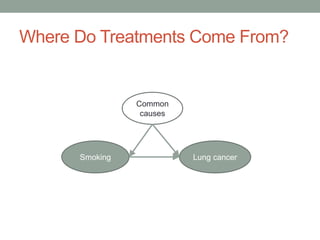

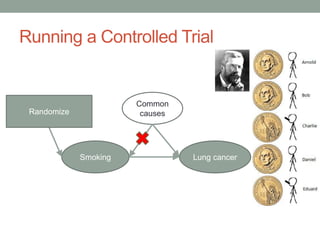

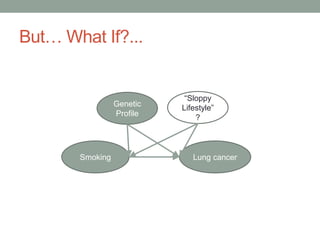

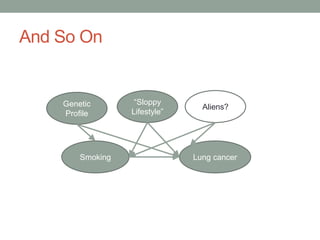

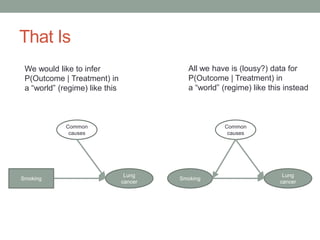

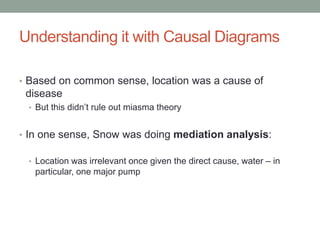

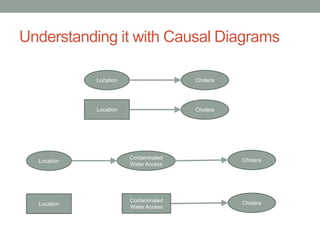

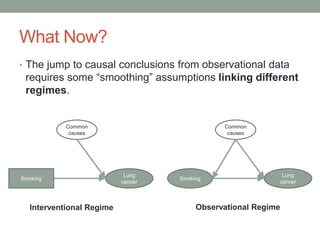

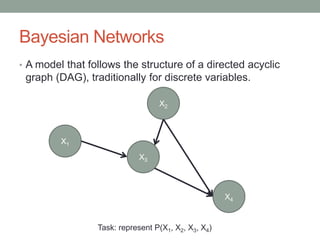

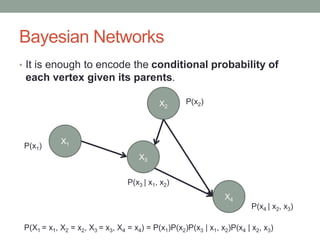

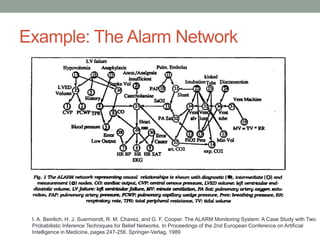

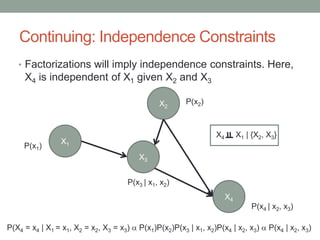

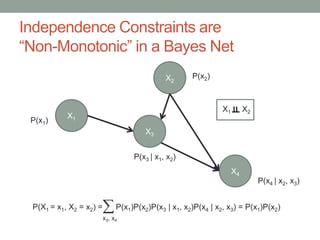

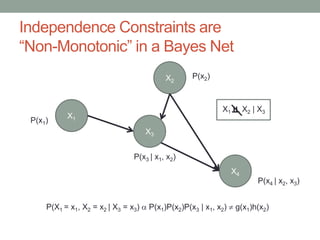

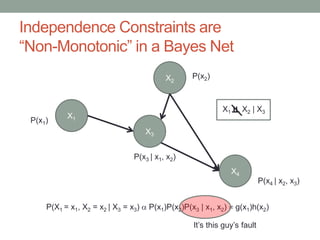

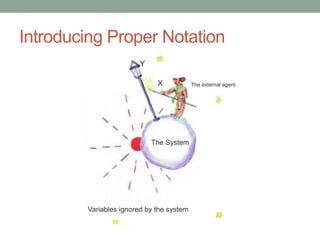

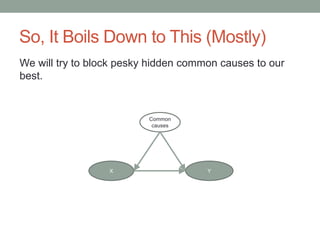

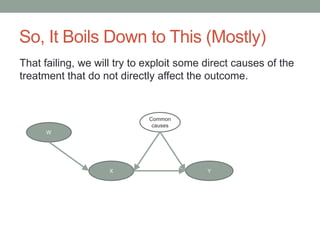

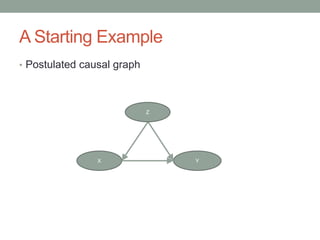

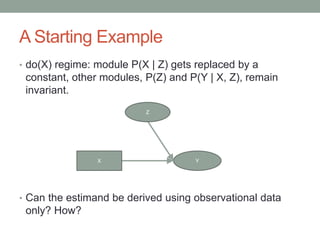

The document discusses causal inference and its relationship with Bayesian networks and experimental design. It outlines key concepts such as treatment, control, and explanation, highlighting the importance of learning from actions and observational studies to infer causal effects. It also emphasizes the necessity of understanding the framework and limitations of these inferential methods in real-world scenarios.

![Learning from Data

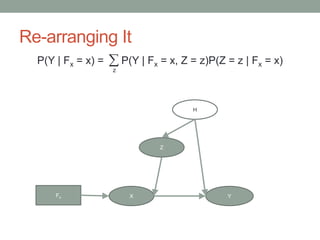

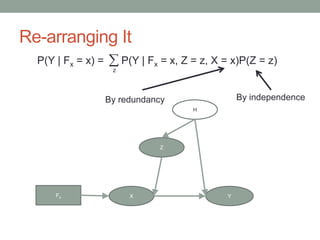

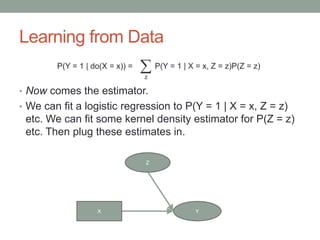

• Alternatively, we can fit some P(X = x | Z = z)

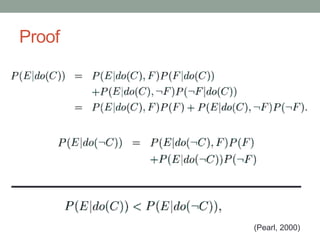

• We can then go through our data points {X(i), Y(i), Z(i)} and

do the following. Since P(Y = 1 | do(X)) = E[Y | do(X)],

• This is sometimes called a “model-free” estimator, as it

doesn’t fully specify a model.

I(X(i) = x)Y(i)

i P(X(i) = x | Z(i) = z(i))

P(Y = 1 | do(X = x)) 1

N

N](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bayesiannetworksandthesearchforcausality-151021145704-lva1-app6892/85/Bayesian-networks-and-the-search-for-causality-80-320.jpg)

![Learning from Data

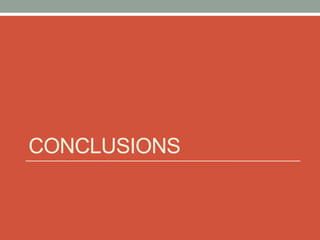

• Recall the sum rule

P(Y = 1 | X = x, Z = z)P(X = x | Z = z)P(Z = z)

z

I(X = x)Y

P(X | Z)

E[ ] =

P(X = x | Z = z)

P(Y = 1 | do(X = x)) = P(Y = 1 | X = x, Z = z)P(Z = z)

z](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bayesiannetworksandthesearchforcausality-151021145704-lva1-app6892/85/Bayesian-networks-and-the-search-for-causality-81-320.jpg)