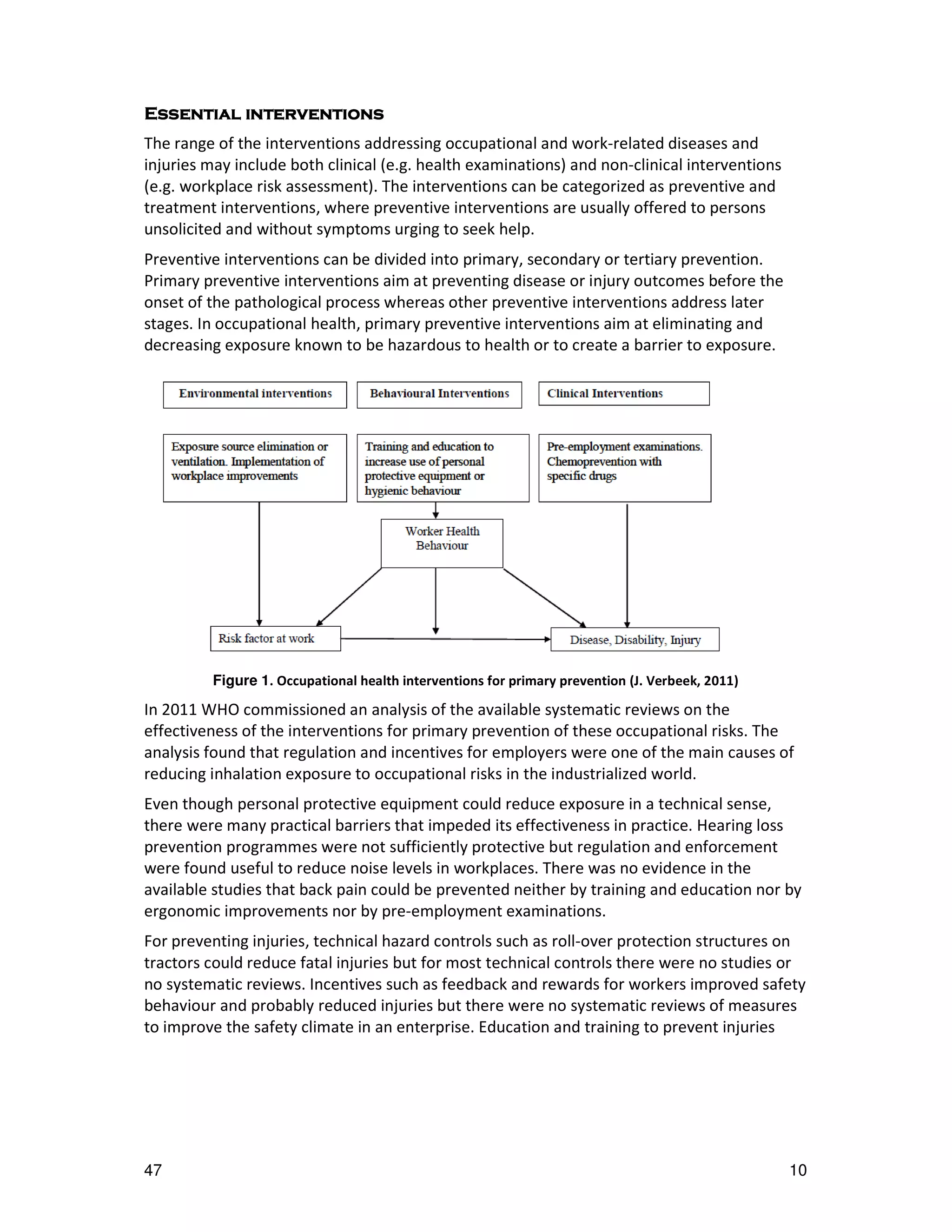

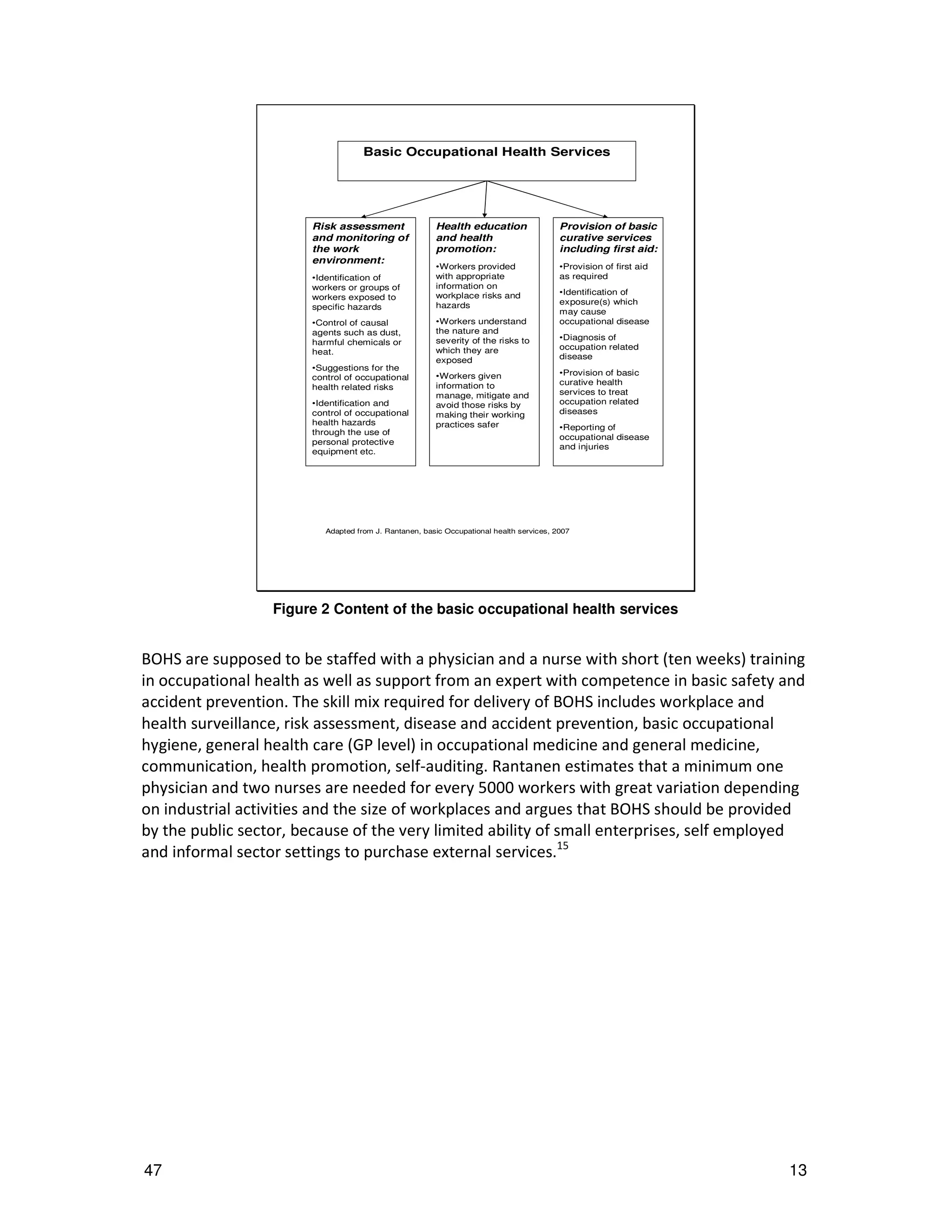

This document discusses integrating occupational health services into primary health care. It argues that while some countries have made progress expanding occupational health services, coverage remains low globally. Most workers, especially in informal sectors and small businesses, lack access to even basic services. The document calls for strengthening primary health care systems based on the principles of the 1978 Alma Ata Declaration, including providing universal access to essential health interventions and services. Integrating occupational health into primary care could help extend coverage of basic services to more workers and their communities through workplace and community-based delivery models.