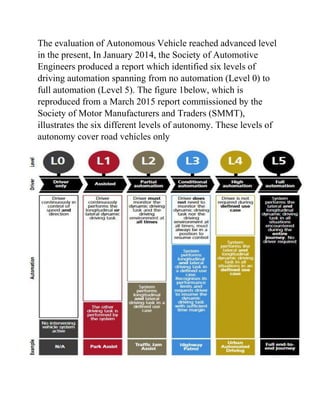

This report examines the history, current status, and future of autonomous vehicles, highlighting their operational theory and impact on economic and energy usage. Key insights include the technological advancements in self-driving systems developed by major companies, the evolution of driving automation levels, and significant challenges in manufacturing autonomous vehicles. The report also discusses potential energy implications, emphasizing that while automation could reduce energy demand, fully autonomous vehicles may lead to increased travel and energy use, necessitating careful policy alignment.