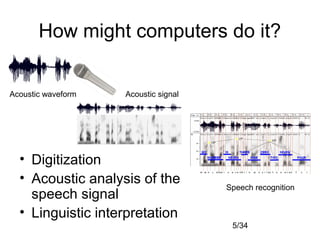

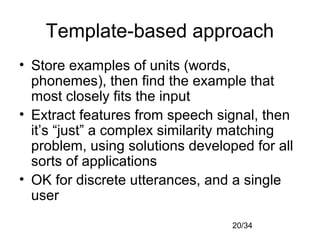

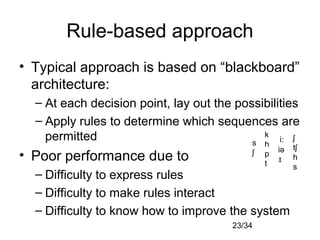

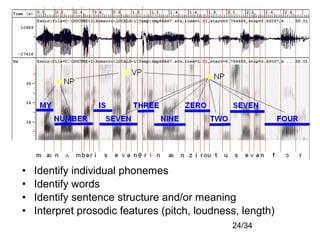

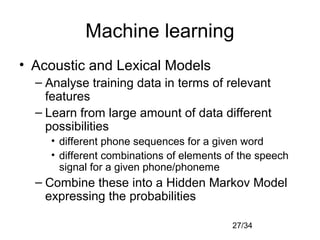

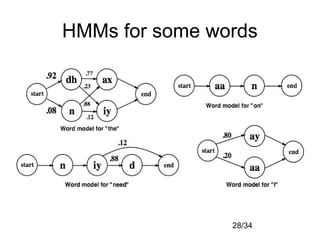

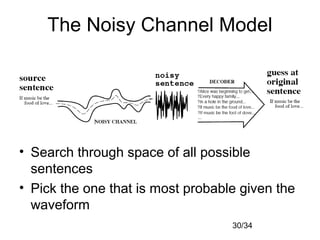

Automatic speech recognition systems aim to convert spoken language into text. There are several challenges, including variability in individual speech, distinguishing similar sounds, and interpreting context. Traditional approaches use templates or rules to recognize speech, but modern statistical approaches use machine learning on large datasets to build acoustic and language models that assign probabilities to possible word sequences. While performance has improved significantly, challenges remain including robustness to varying conditions, handling disfluencies in spontaneous speech, and recognizing accents and mixed languages.