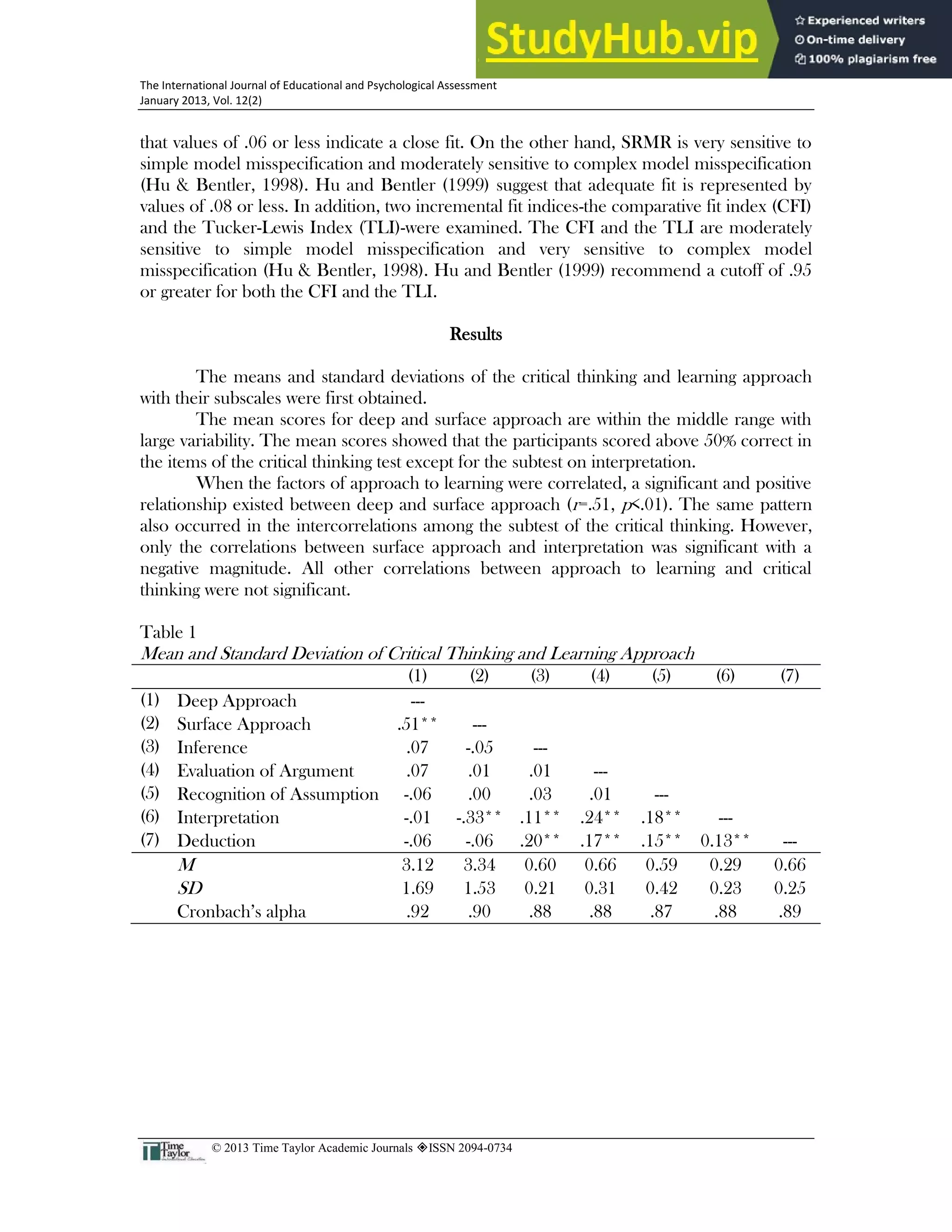

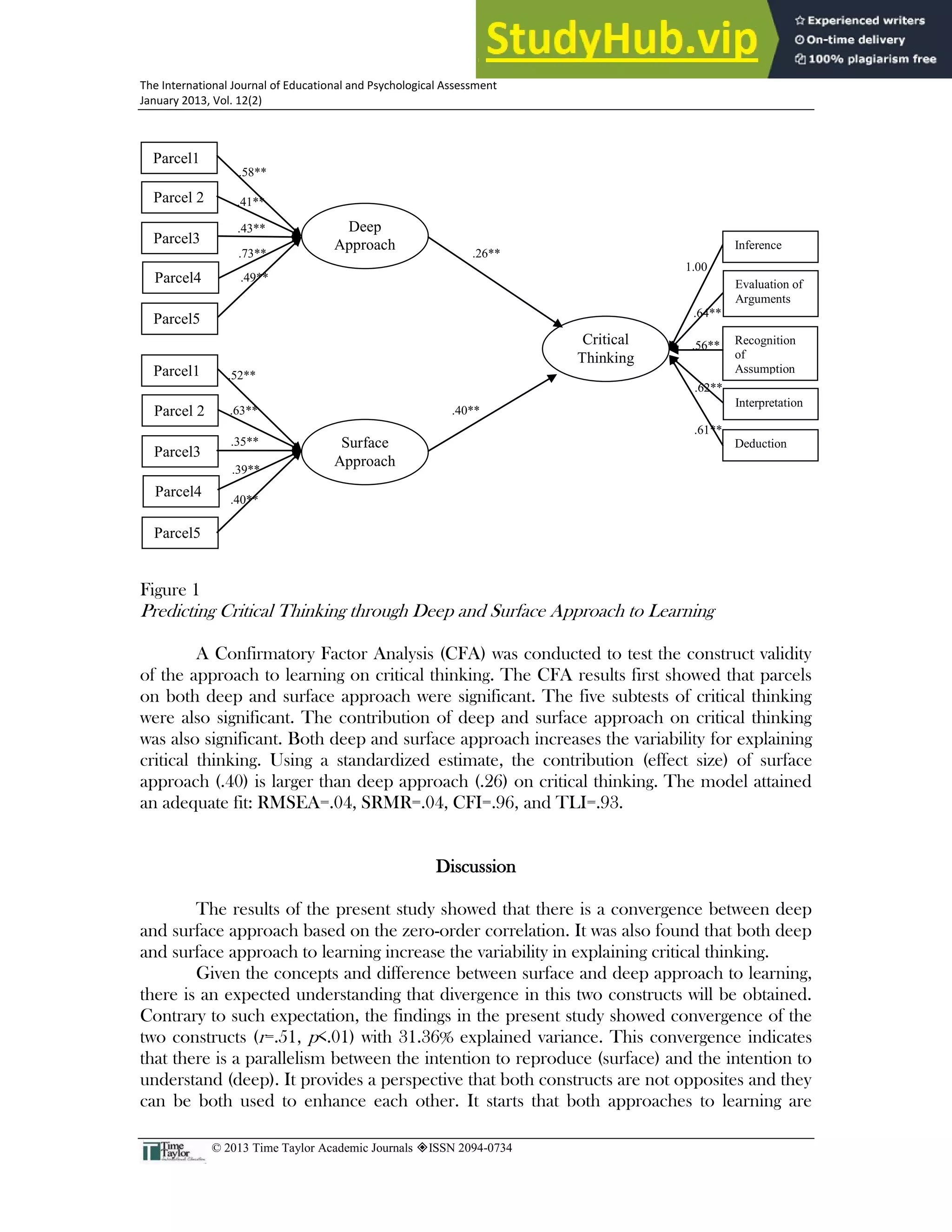

The document discusses a study that explored the relationship between students' approaches to learning and critical thinking abilities. The study administered the Revised Learning Process Questionnaire and Watson-Glaser Critical Thinking Appraisal to 104 high school students. Confirmatory factor analysis showed that both deep and surface learning approaches increased the variance explained in students' critical thinking abilities. Only surface learning approach was significantly correlated with the interpretation subtest of the critical thinking appraisal.

![25

The International Journal of Educational and Psychological Assessment

January 2013, Vol. 12(2)

© 2013 Time Taylor Academic Journals ISSN 2094-0734

Deep and surface approaches to study was derived from the original empirical

research by Marton and Säljö (1976) and Entwistle and Ramsden (1983) and elaborated by

Biggs and among others. Although learners may be classified as “deep” and “surface” they

are not attributes of an individual, one person may use both approaches at different times,

although he or she may have preferences for one or the other. The use of deep approach

manifest high critical thinking skills that focuses on “what is signified”, relates knowledge to

new knowledge, relates and distinguishes evidence and arguments, organizes and structure

content into coherent whole and emphasis is internal, from within the students while the

use of surface approach shows low critical thinking that only focuses on “signs” (or on the

learning as a signifier of something else), focuses on unrelated parts of the task, information

for assessment is simple memorized, facts and concepts are associated unreflectively,

principles are not distinguished from examples, task is treated as an external imposition

and emphasis is external from the demands of assessment (Biggs, 1993). The present study

validates the functional use of approaches to learning in promoting critical thinking among

secondary education students.

Method

Participants

There were 104 senior high school seniors students in a private school in the

Philippines. The participants came from three sections. The students were all in their

senior years enrolled in a private school and were undergoing the same curriculum.

Instruments

To measure learning approach, the researcher used the Revised Learning Process

Questionnaire (R-LPQ) developed by Kember, Biggs, and Leung (2001). The

questionnaire consists of 22 items. It is provided with two approach scores (1) deep

approach and (2) surface approach. It uses a five point Likert scale ranging from “always”

or “almost always true of me” to “never” or “only rarely true of me”. The alpha coefficient

obtained is .71 for the combine scale and .62 for deep approach and .54 for surface

approach.

To measure the critical thinking, the Watson-Glaser Critical Thinking Appraisal

Test (WGCTA) was used which consist of series of tests exercises which require

application of some of the important abilities involved in critical thinking. The exercises

include problems, statements, arguments, and interpretations of data. It is a test of power

with no rigid time limit. The five subtests are as follows: Inference (samples ability to

discriminate among degrees of truth or falsity of interferences drawn from given data),

Recognition of Assumptions (samples ability to recognize unstated assumptions or

presuppositions which are taken for granted in given statements or assertions), Deduction

(samples ability to reason deductively from given statements or premises; to recognize the

relation of implication between propositions; to determine whether what may seem to be

an implication of necessary implication or necessary interference from given premises),

Interpretations (samples ability to weigh evidence and to distinguish between [a]

generalizations from given data that are not warranted beyond a reasonable doubt; [b]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/assessingstudentscriticalthinkingandapproachestolearning-230805200211-a6eb28d9/75/Assessing-Students-Critical-Thinking-And-Approaches-To-Learning-7-2048.jpg)