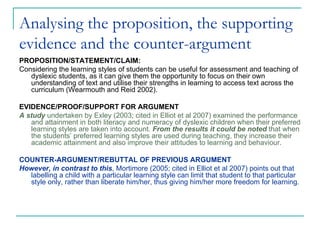

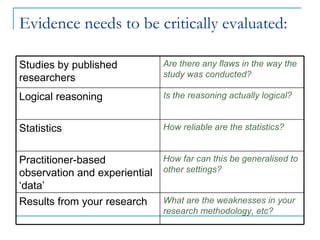

This document discusses constructing arguments in academic assignments. It defines an argument as having a claim supported by evidence. An example is provided of a claim about considering learning styles benefiting dyslexic students, supported by a study finding academic improvements. However, another study notes labeling students could limit learning styles. The document asks what counts as evidence and discusses critically evaluating evidence sources. It poses further questions about building complete arguments in essays using connecting words to link different parts logically.