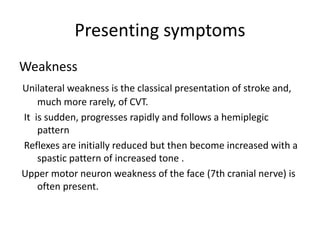

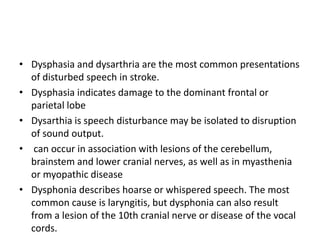

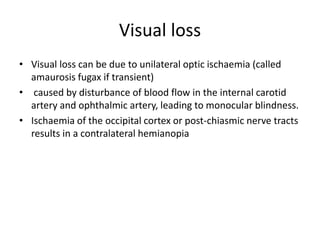

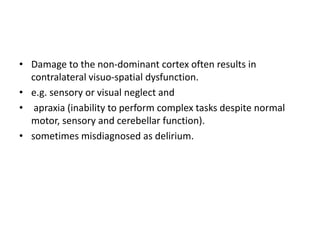

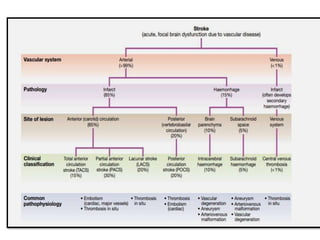

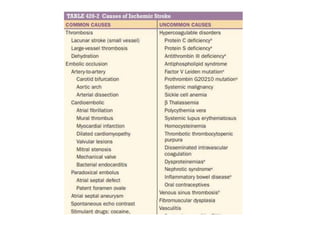

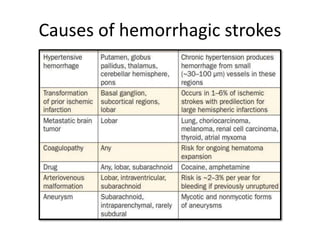

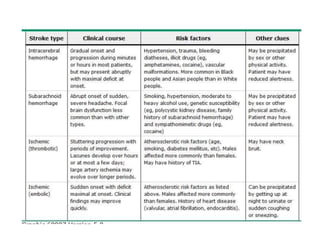

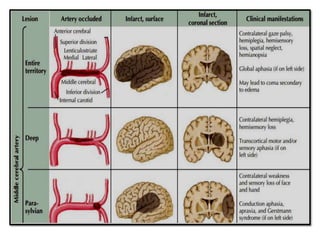

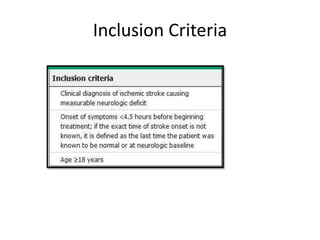

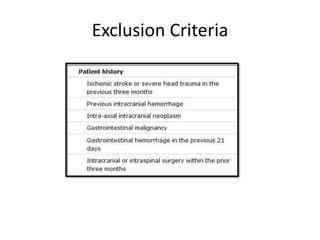

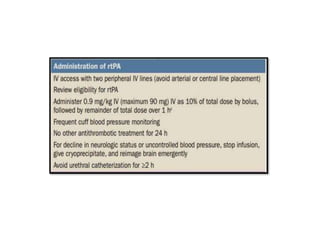

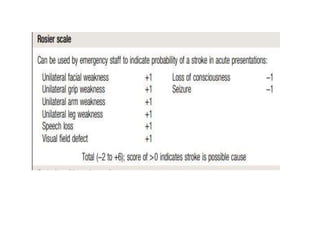

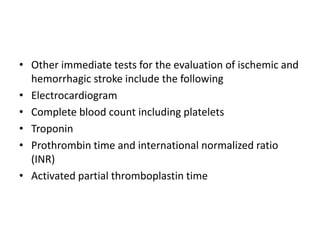

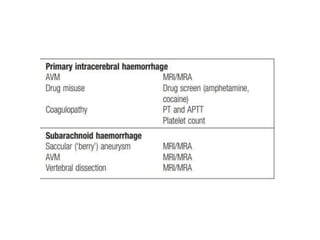

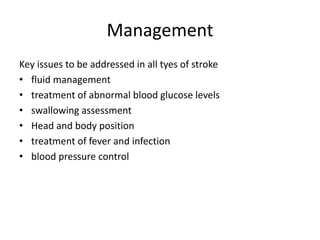

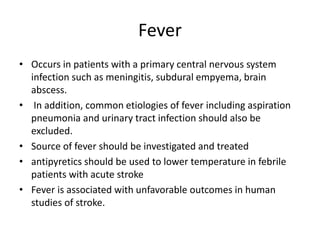

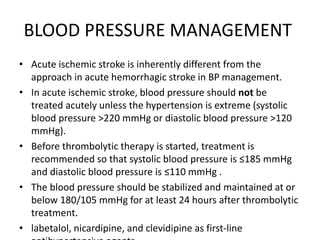

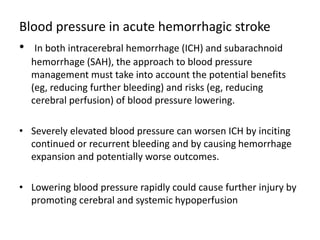

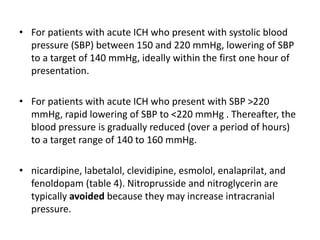

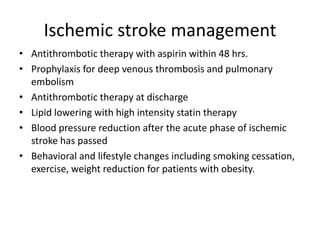

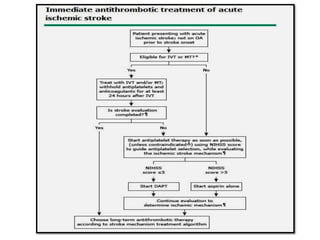

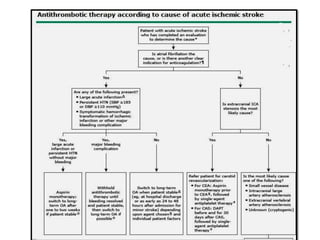

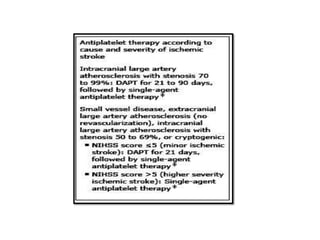

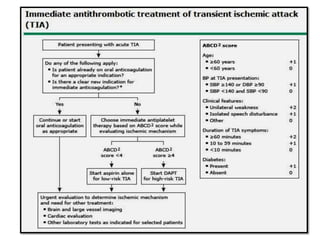

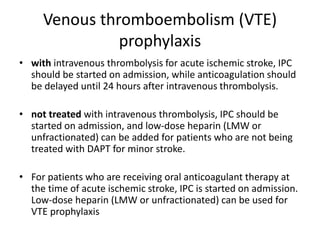

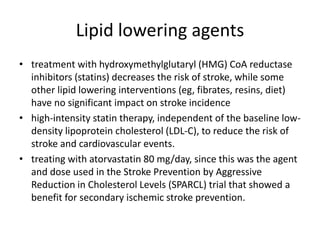

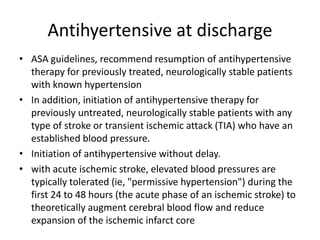

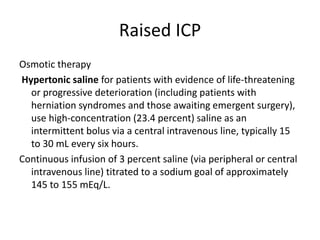

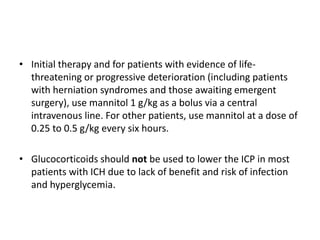

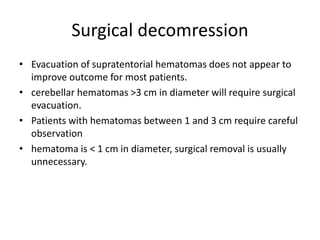

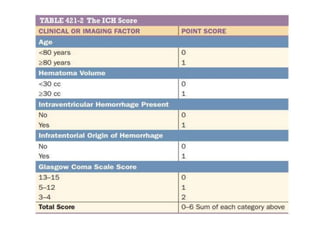

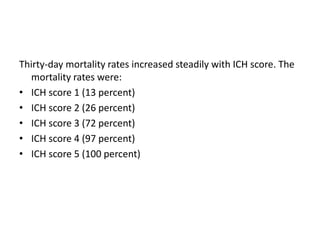

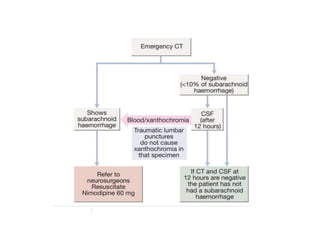

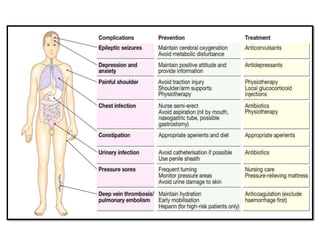

This document provides an overview of strokes, including definitions, classifications, clinical features, investigations, and management approaches. It defines different types of strokes such as transient ischemic attack, minor stroke, and stroke in evolution. Key points covered include: initial assessment focuses on ABCs and identifying candidates for reperfusion therapies; imaging helps determine etiology and guides management; factors like fever, blood pressure, and swallowing require attention; and prevention of complications like DVT is important. Management differs between ischemic versus hemorrhagic strokes, with the latter requiring reversal of anticoagulation and surgical intervention in some cases. Prognostic scoring systems can estimate mortality from intracerebral hemorrhage.