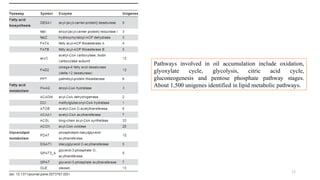

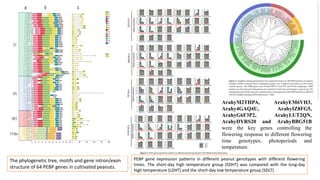

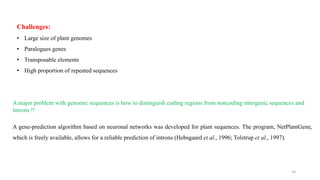

The document discusses genomics in plant breeding, emphasizing structural, functional, and comparative genomics while detailing various techniques such as CRISPR/Cas9, genome sequencing, and transcriptomics. It explores applications in enhancing traits like disease resistance, abiotic stress tolerance, and nutritional quality in crops. Furthermore, it covers the significance of bioinformatics and pangenomics in understanding genetic diversity and improving plant breeding programs.