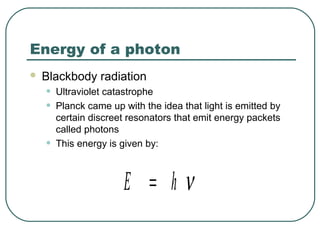

1. The document provides an overview and review of topics covered on the AP Physics B exam related to modern physics, including the photoelectric effect, Bohr model of the atom, and nuclear physics.

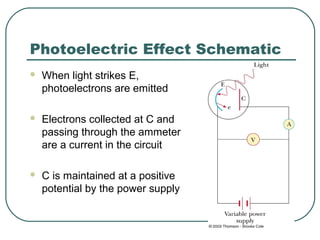

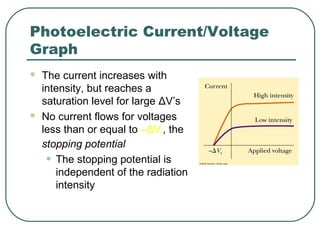

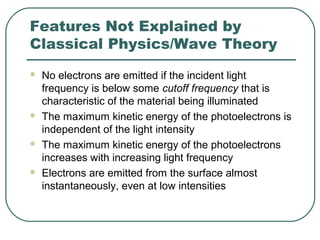

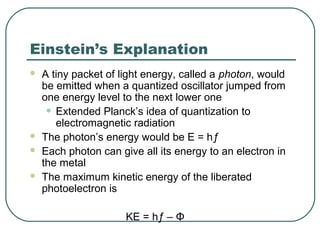

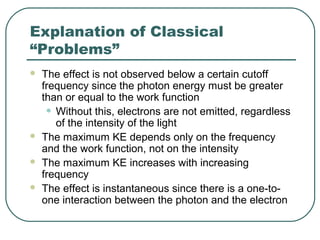

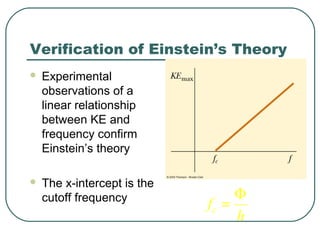

2. It describes Einstein's explanation of the photoelectric effect involving photons and how it resolved issues not explained by classical wave theory.

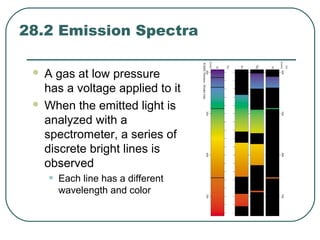

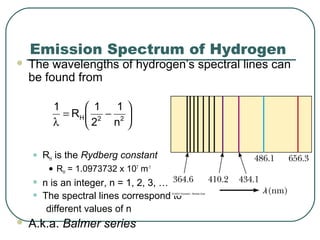

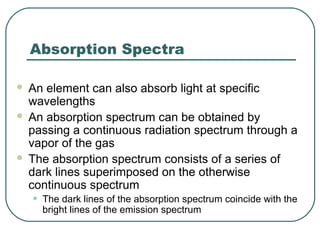

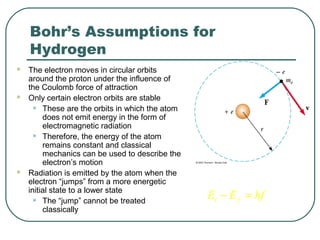

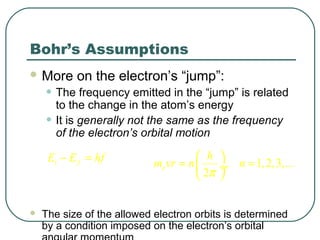

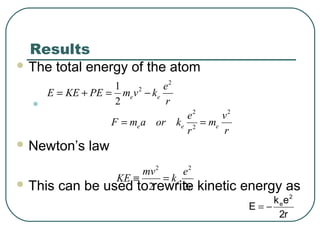

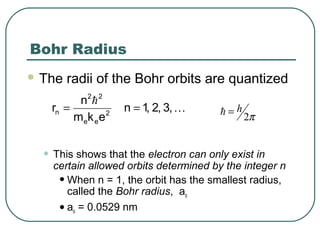

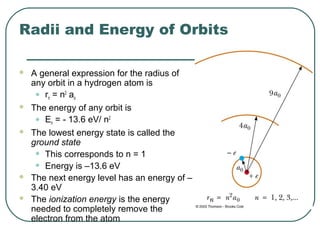

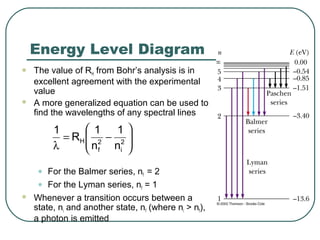

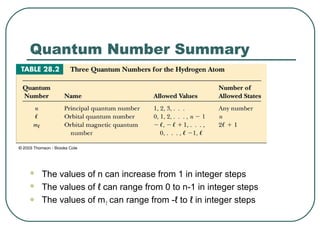

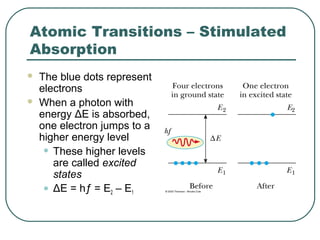

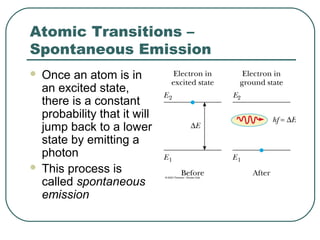

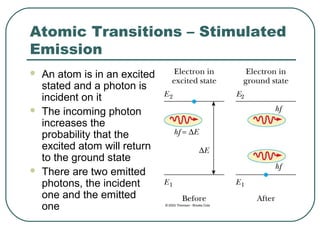

3. It also explains the Bohr model of the hydrogen atom, including Bohr's assumptions and how it leads to quantized electron orbits that can explain atomic emission spectra.