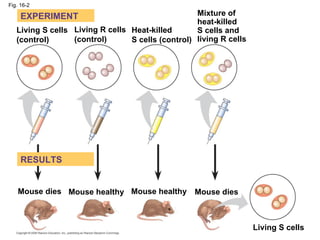

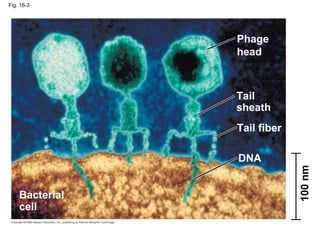

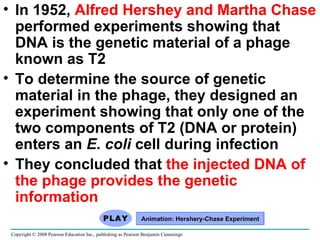

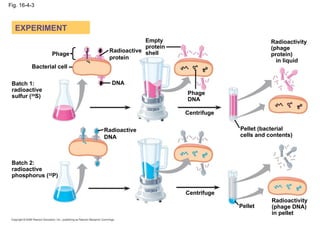

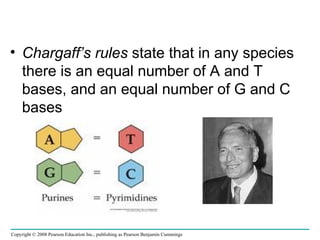

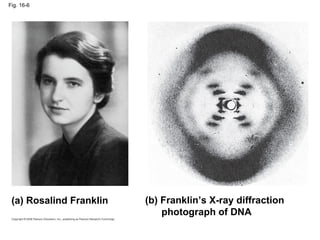

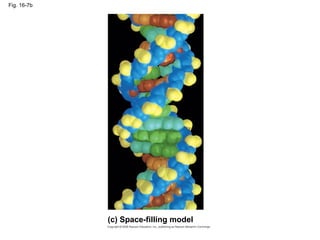

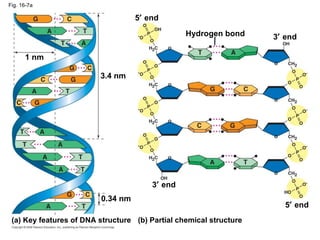

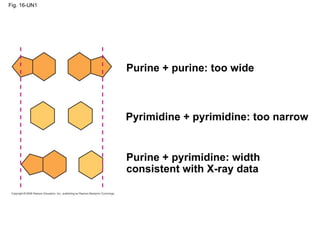

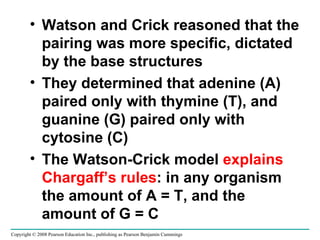

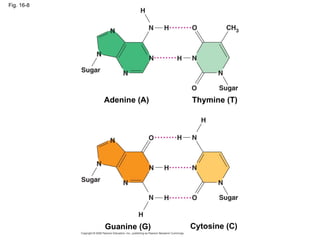

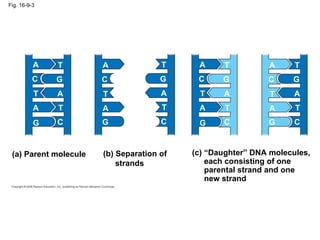

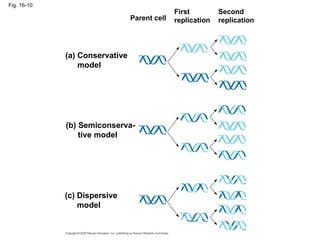

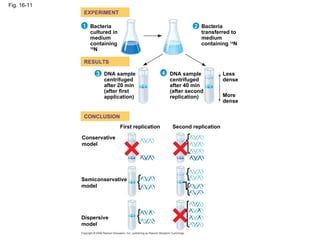

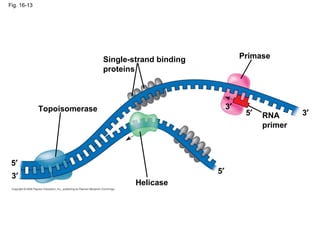

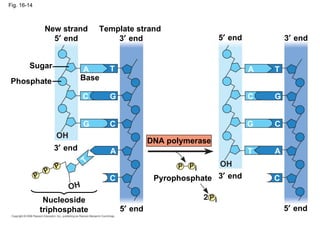

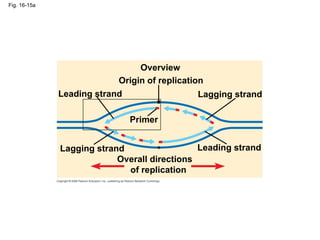

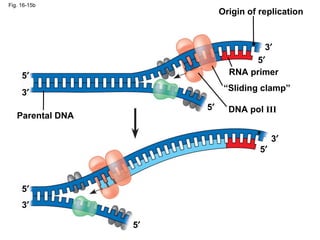

The document summarizes key discoveries in establishing DNA as the genetic material. It describes experiments by Griffith, Avery, Hershey and Chase showing that DNA transforms bacteria and is the genetic material in viruses. Watson and Crick developed the double helix model of DNA structure based on Franklin's X-ray images, explaining Chargaff's rules. Their model suggested DNA replication is semiconservative, supported by Meselson-Stahl experiments. DNA polymerase synthesizes new DNA strands while helicase and ligase aid replication.