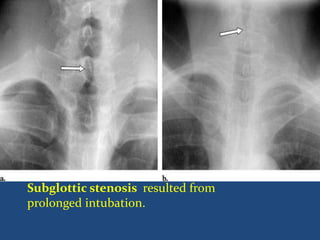

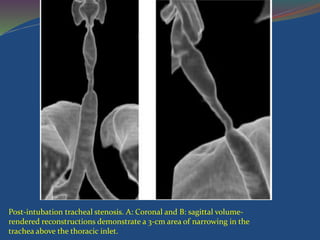

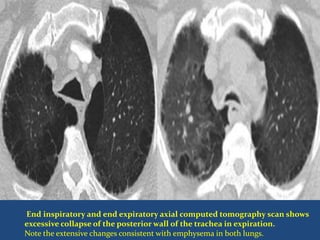

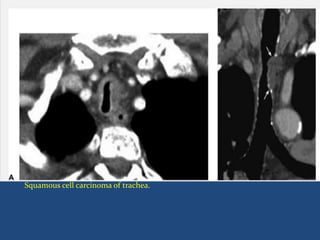

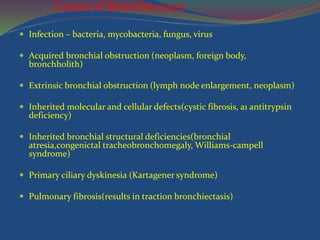

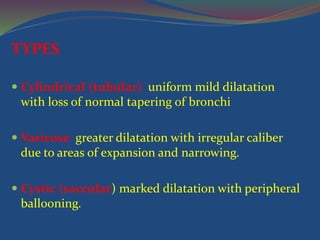

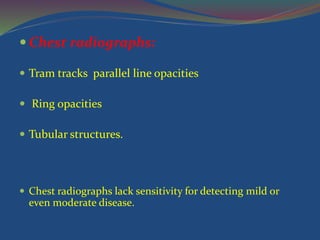

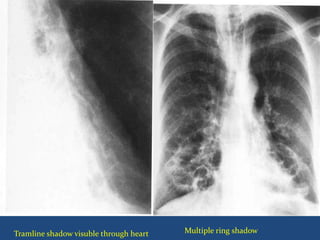

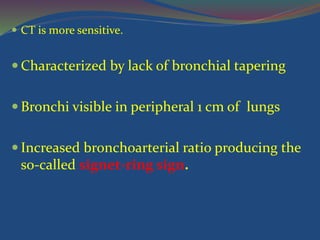

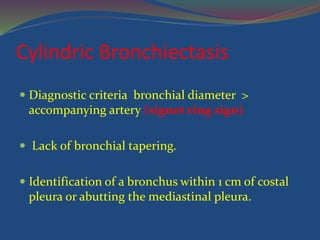

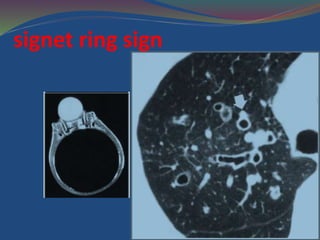

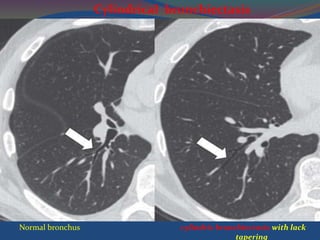

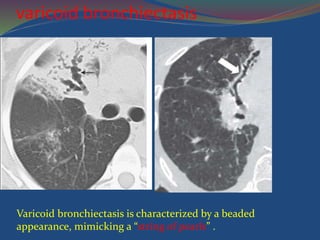

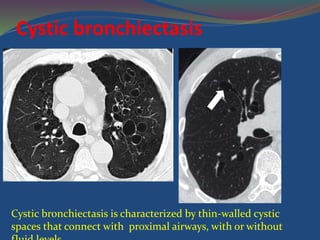

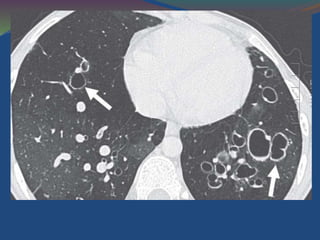

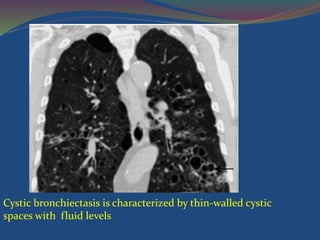

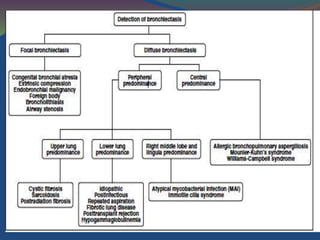

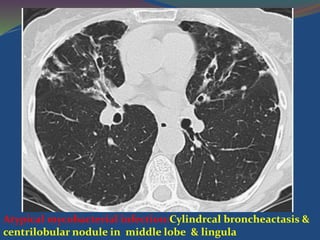

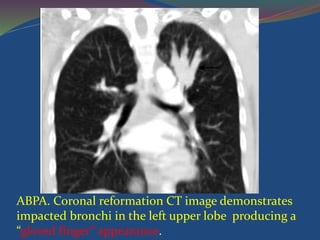

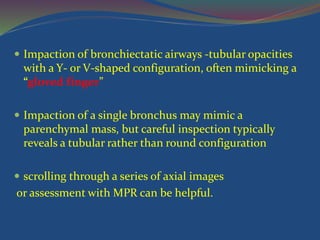

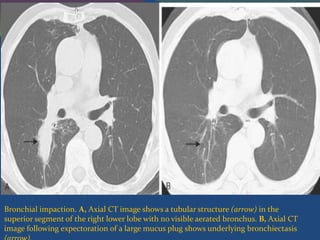

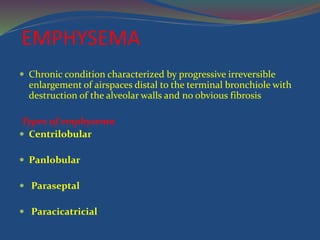

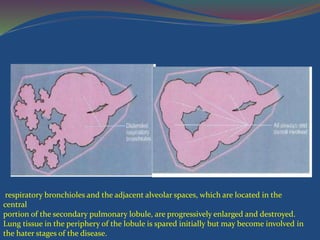

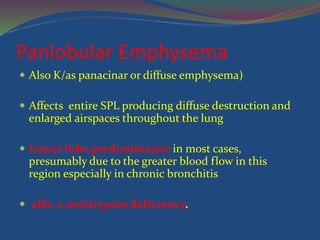

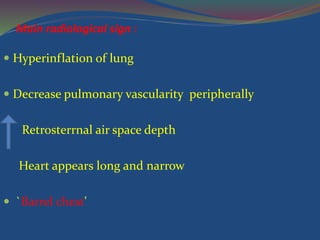

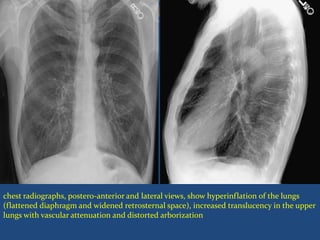

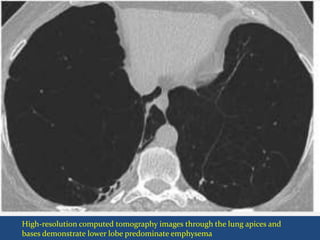

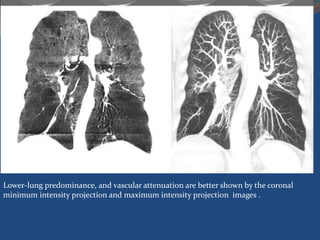

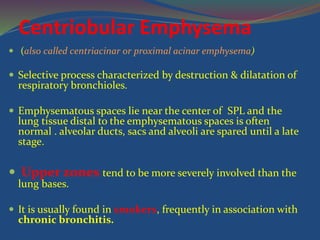

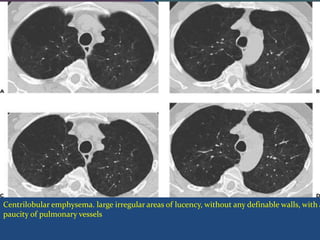

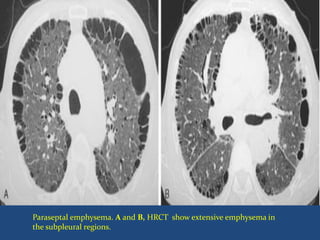

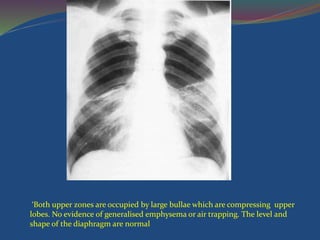

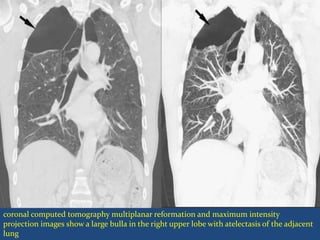

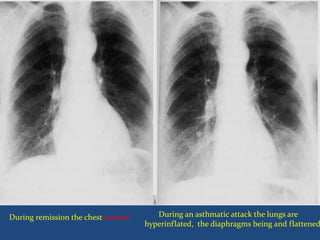

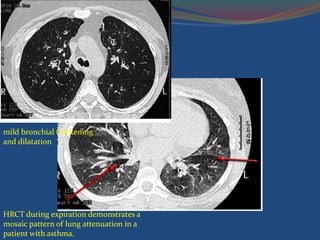

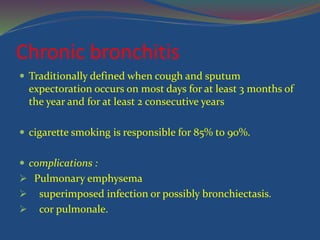

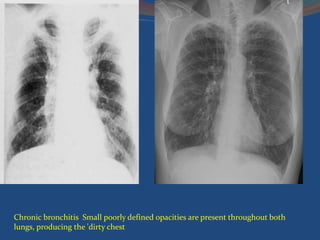

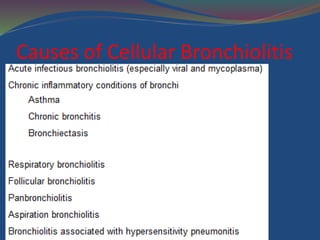

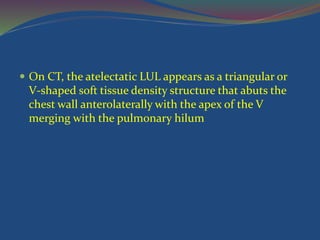

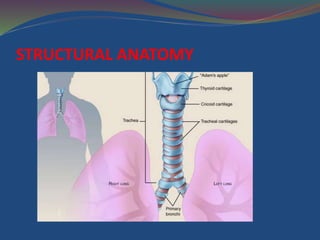

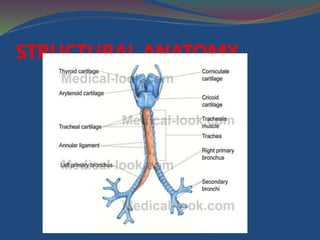

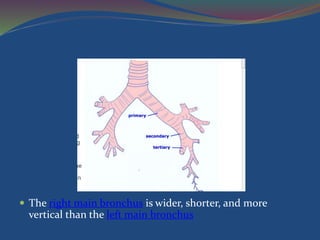

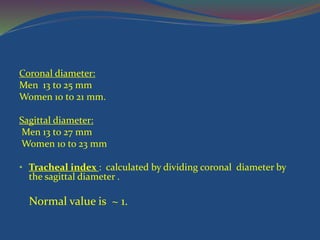

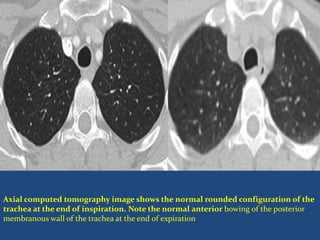

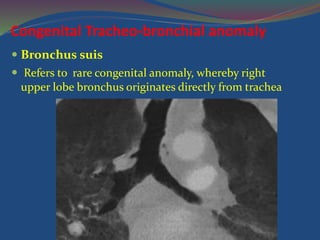

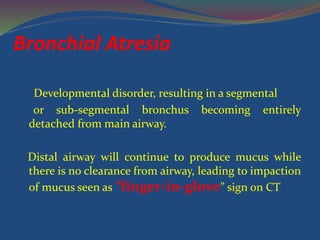

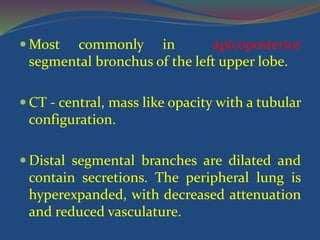

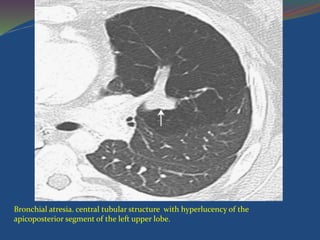

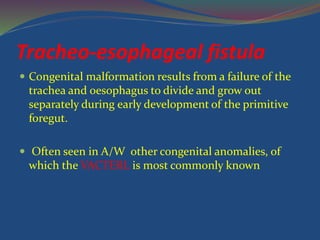

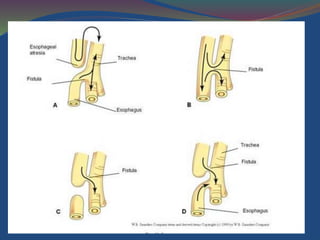

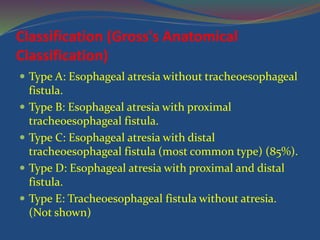

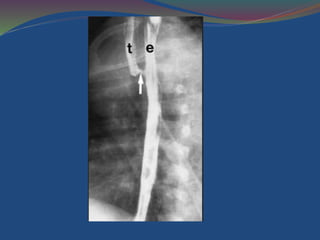

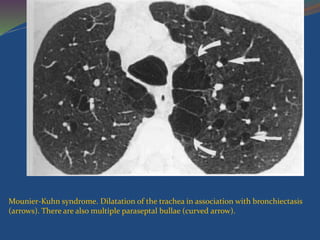

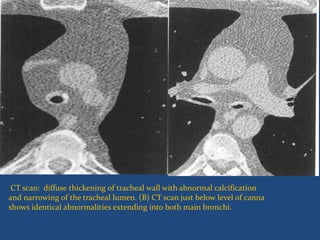

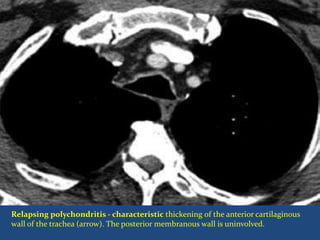

This document provides information on the anatomy and structural abnormalities of the trachea and bronchi. It begins with a description of the normal anatomy of the trachea including its length, diameter, cartilage structure, and changes during inspiration and expiration. It then discusses various congenital anomalies such as bronchus suis, bronchial atresia, and tracheoesophageal fistula. Acquired conditions of the trachea and bronchi are also summarized such as tracheobronchomegaly, saber sheath trachea, relapsing polychondritis, stenosis, malacia, and neoplasms. Common lung diseases like bronchiectasis, emphysema, asthma, and chronic bronchitis are briefly explained as well.

![ Iatrogenic

Postintubation

Lung transplantation

Infection

Laryngotracheal papillomatosis[*]

Rhinoscleroma

Tuberculosis

Tracheal neoplasm

Systemic diseases

Amyloidosis

Inflammatory bowel disease

Relapsing polychondritis

Sarcoidosis

Wegener granulomatosis](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/airwaydisease-150121023854-conversion-gate02/85/Air-way-disease-29-320.jpg)