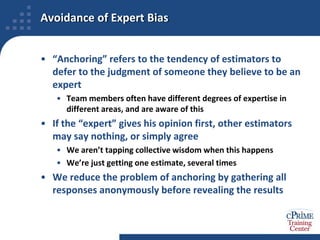

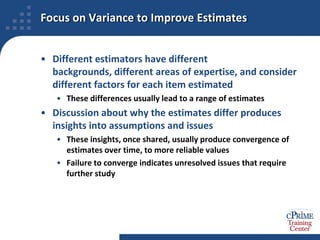

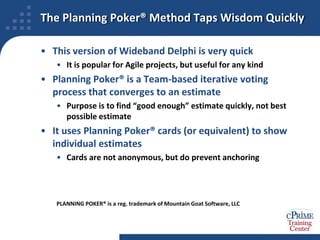

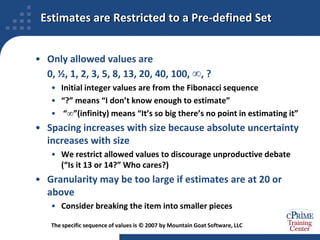

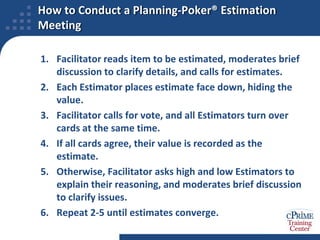

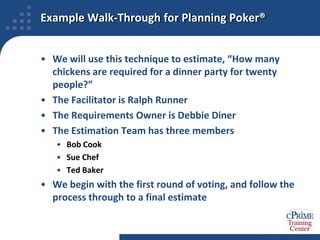

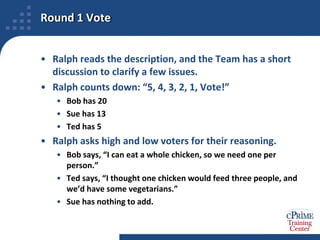

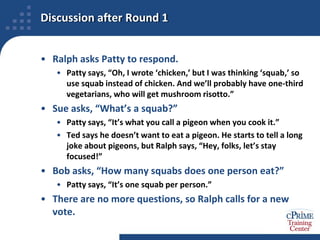

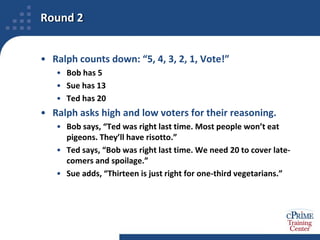

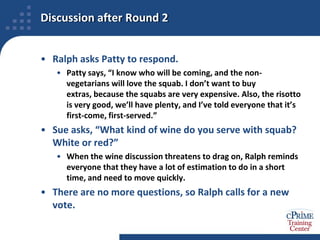

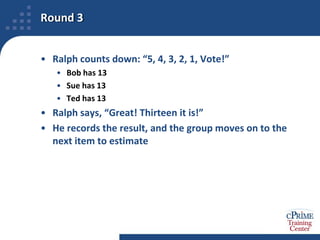

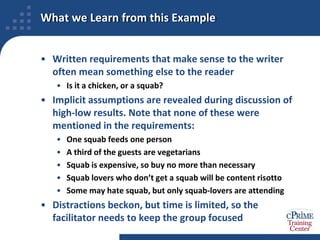

The document describes a method called "Planning Poker" for quickly estimating project tasks through group discussion and iterative voting. A facilitator leads a team in estimating how many chickens are needed for a dinner party for 20 people. Through three rounds of voting and discussion to clarify assumptions, the team converges on an estimate of 13 chickens. Planning Poker aims to leverage collective expertise while avoiding biases from individual experts.