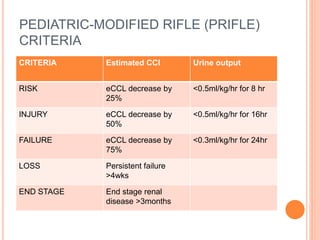

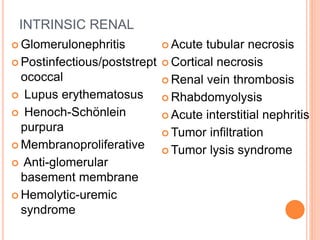

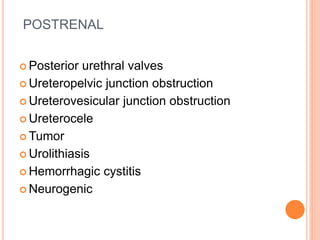

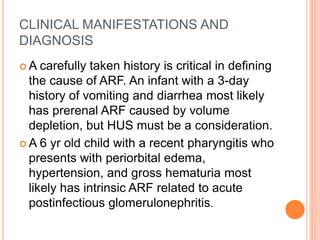

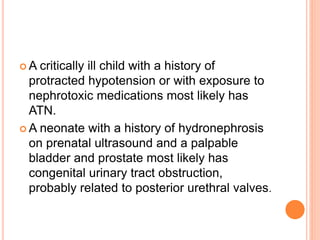

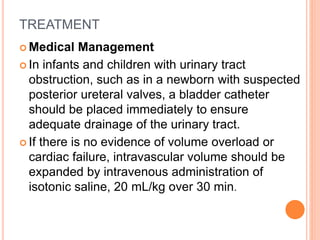

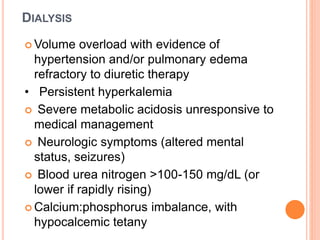

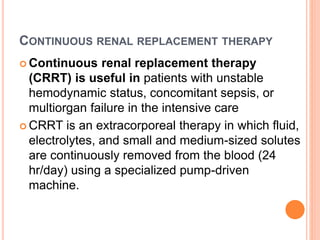

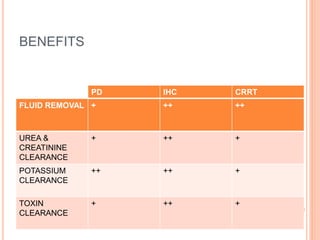

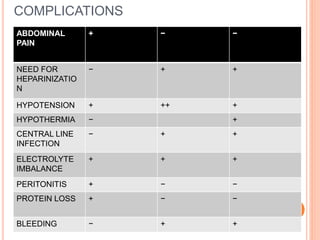

Acute renal failure (ARF) is a clinical syndrome characterized by a sudden deterioration in renal function resulting in the inability to maintain fluid and electrolyte homeostasis. A modified pediatric RIFLE criteria (pRIFLE) has been developed to characterize acute kidney injury in children. ARF can be prerenal, intrinsic renal, or postrenal in etiology. Treatment involves fluid resuscitation, management of electrolyte abnormalities, and potentially dialysis. Prognosis depends on the underlying cause, with renal-limited conditions having a low mortality and multiorgan failure a high mortality.