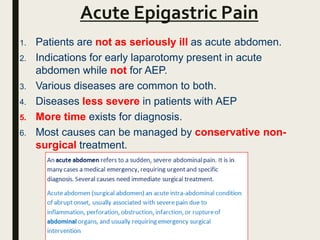

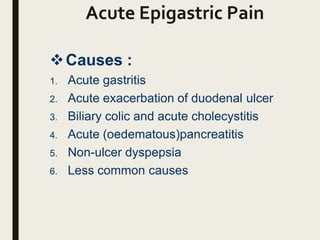

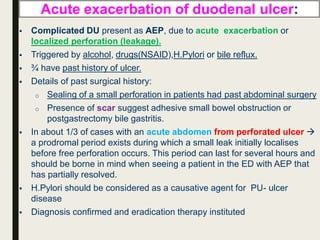

The document discusses acute epigastric pain, dividing it into causes such as acute gastritis, exacerbation of duodenal ulcer, biliary colic, acute cholecystitis, and acute pancreatitis. For each cause, it describes the typical history, examination findings, diagnostic tests, and treatment approach. For example, it notes that acute gastritis is often caused by H. pylori or NSAIDs, while acute cholecystitis presents with right upper quadrant tenderness and Murphy's sign on examination. Ultrasound is useful for gallstones, while lipase checks for pancreatitis. Treatment focuses on conservative measures, though cholecystectomy may be considered for cholecystitis.