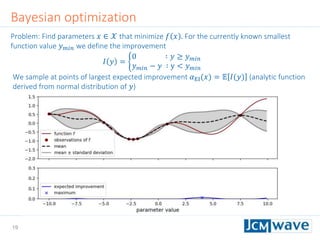

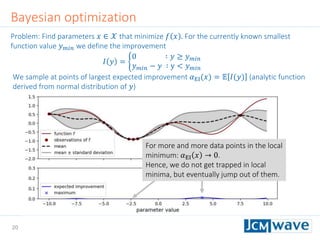

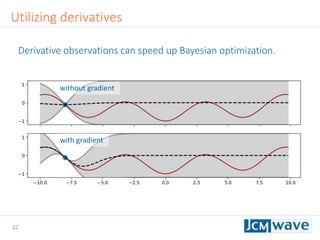

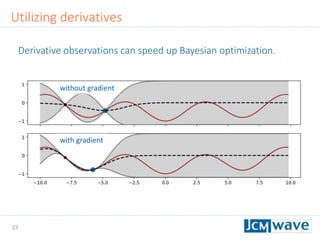

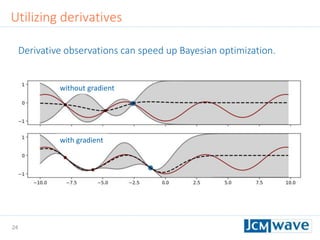

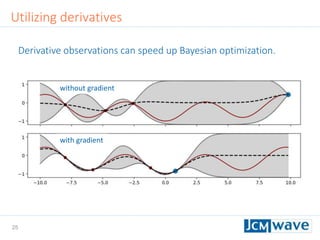

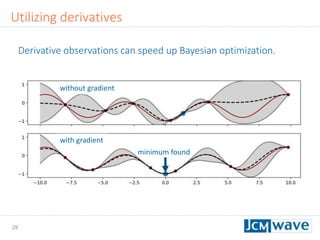

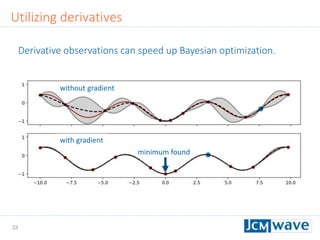

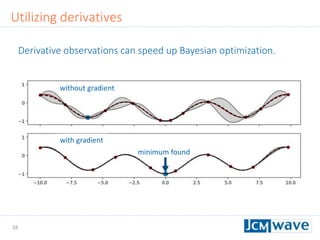

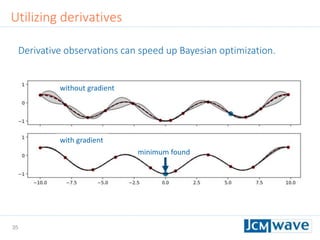

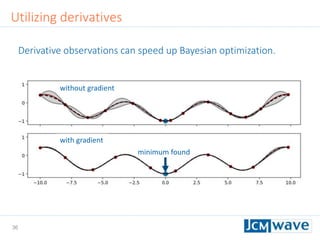

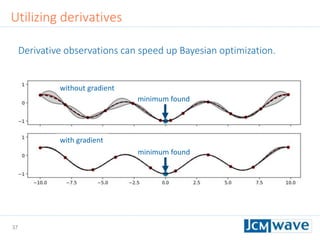

The document describes a machine learning method for efficient design optimization in nano-optics using Gaussian process regression and Bayesian optimization. It discusses how Gaussian process regression can be used to build regression models from expensive black-box functions to enable model-based optimization and integration. Bayesian optimization is then used to iteratively query the black-box function at points of maximum expected improvement to find its minimum. The method can incorporate derivative observations to speed up optimization by providing additional training data for the Gaussian process. Differential evolution is also utilized to efficiently maximize the expected improvement at each iteration. The approach is demonstrated on benchmark optimization problems, showing it outperforms other algorithms like L-BFGS and particle swarm optimization.

![5

+ Accurate and data

efficient

+ Reliable (provides

uncertainties)

+ Interpretable results

‒ Computationally

demanding but not as

much as training neural

networks

Regression models (small selection)

K-nearest neighbors

Linear regression

Support vector machine

Random forest trees

Gaussian process

regression (Kriging)

(Deep) neural networks

[CE Rasmussen, “Gaussian processes in machine learning”. Advanced lectures on machine

learning , Springer (2004)]

[B. Shahriari et al., "Taking the Human Out of the Loop: A Review of Bayesian Optimization“.

Proc. IEEE 104(1), 148 (2016)]

Increasingpredictivepower

andcomputationaldemands](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/jcmwaveoptimzecompiled-190622220529/85/A-machine-learning-method-for-efficient-design-optimization-in-nano-optics-5-320.jpg)

![7

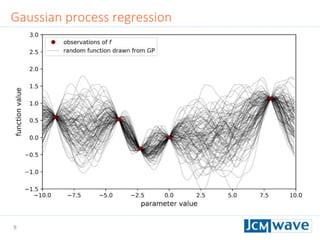

Gaussian process (GP): distribution of functions in a continuous domain 𝒳 ⊂ ℝN

Defined by: mean function 𝜇: 𝒳 → ℝ and covariance function (kernel) 𝑘: 𝒳 × 𝒳 → ℝ

Training data: 𝑀 known function values 𝑓 𝑥1 , … , 𝑓 𝑥 𝑀 with corresponding

covariance matrix 𝐊 = 𝑘 𝑥𝑖, 𝑥𝑗 𝑖,𝑗

Random function values at positions 𝐗∗

= (𝑥1

∗

, … , 𝑥 𝑁

∗

):

Multivariate Gaussian random variable 𝐘∗

∼ 𝒩 𝛍, 𝚺 with probability density

𝑝 𝐘∗

=

1

2𝜋 𝑁/2 𝚺 1/2

exp −

1

2

𝐘∗

− 𝛍 𝑇

𝚺−1

𝐘∗

− 𝛍 ,

means, and covariance

𝛍𝑖 = 𝜇(𝑥𝑖

∗

) −

𝑘𝑙

𝑘 𝑥𝑖

∗

, 𝑥 𝑘 𝐊 𝑘𝑙

−1

[𝑓 𝑥𝑙 − 𝜇 𝑥𝑙 ]

𝚺𝑖𝑗 = 𝑘 𝑥𝑖

∗

, 𝑥𝑗

∗

−

𝑘𝑙

𝑘 𝑥𝑖

∗

, 𝑥 𝑘 𝐊 𝑘𝑙

−1

𝑘 𝑥𝑙, 𝑥𝑗

∗

.

For a proof see:

http://fourier.eng.hmc.edu/e161/lectures/gaussianprocess/node7.html

Gaussian process regression](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/jcmwaveoptimzecompiled-190622220529/85/A-machine-learning-method-for-efficient-design-optimization-in-nano-optics-7-320.jpg)

![9

In the following we don’t need correlated random vectors of

function values, but just the probability distribution of a

single function value 𝑦 at some 𝑥∗

∈ 𝒳

This is simply a normal distribution 𝑦 ∼ 𝒩( 𝑦, 𝜎2

) with mean

and standard deviation

𝑦 = 𝜇 𝑥∗ +

𝑖𝑗

𝑘 𝑥∗, 𝑥𝑖 𝐊 𝑖𝑗

−1

[𝑓 𝑥𝑗 − 𝜇 𝑥𝑗 ]

𝜎2 = 𝑘 𝑥∗, 𝑥∗ − 𝑖𝑗 𝑘(𝑥∗, 𝑥𝑖) 𝐊 𝑖𝑗

−1

𝑘(𝑥𝑗, 𝑥∗)

Gaussian process regression](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/jcmwaveoptimzecompiled-190622220529/85/A-machine-learning-method-for-efficient-design-optimization-in-nano-optics-9-320.jpg)

![42

Rastrigin function

Defined on an 𝑛-dimensional domain as 𝑓 𝒙 = 𝐴𝑛 + 𝑖=1

𝑛

[𝑥𝑖

2

− 𝐴 cos(2𝜋𝑥𝑖)] with

𝐴 = 10. We use 𝑛 = 3 and 𝑥𝑖 ∈ [−2.5,2.5].

Sleeping for 10s during evaluation to make function call “expensive”.

Parallel minimization with 5 parallel evaluations of 𝑓 𝒙 .

Global minimum 𝑓 𝑚𝑖𝑛 = 0 at 𝒙 = 0](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/jcmwaveoptimzecompiled-190622220529/85/A-machine-learning-method-for-efficient-design-optimization-in-nano-optics-42-320.jpg)

![43

Benchmark on Rastrigin function

[Laptop with 2-core Intel Core I7 @ 2.7 GHz]

BO converges significantely faster to the global minimum

Derivative observations improve the convergence

Although more elaborate, BO has no significant computation time

overhead](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/jcmwaveoptimzecompiled-190622220529/85/A-machine-learning-method-for-efficient-design-optimization-in-nano-optics-43-320.jpg)

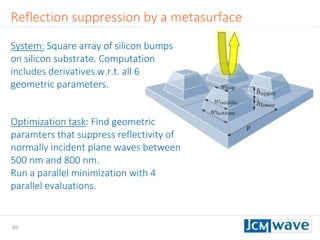

![46

Reflection suppression by a metasurface

Comparison of different global optimization methods

BO more efficient by almost 1 order of magnitude

BO has negligible computation time overhead

[four 10-core Intel Xeon CPUs @ 2.4 GHz]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/jcmwaveoptimzecompiled-190622220529/85/A-machine-learning-method-for-efficient-design-optimization-in-nano-optics-46-320.jpg)