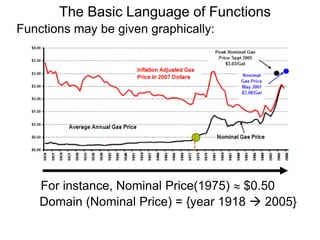

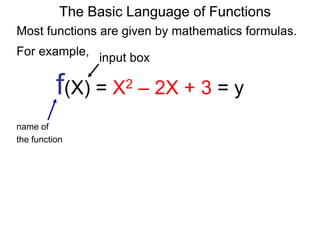

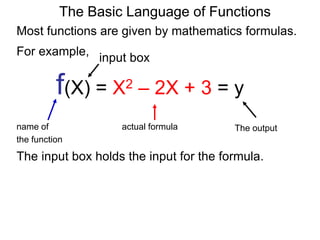

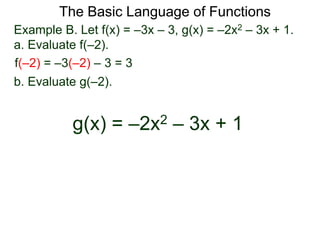

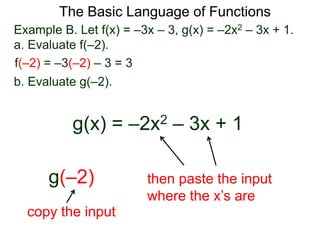

The document defines and explains functions. A function assigns each input exactly one output. Functions can be represented by formulas, tables, or graphs. The domain is the set of all possible inputs, and the range is the set of all possible outputs. Examples demonstrate evaluating functions by substituting inputs into formulas.

![The Basic Language of Functions

Exercise B.

Given the functions

f, g and h, find the

outcomes of the

following expressions.

If it’s not defined,

state so.

x y = g(x)

–1 4

2 3

5 –3

6 4

7 2

y = h(x)

f(x) = –3x + 7

1. f(–1) 2. g(–1) 3.h(–1)

4. –f(3) 5. –g(3) 6. –h(3)

7. 3g(6) 8. 2f(2) 9. h(3) + h(0)

10. 2f(4) + 3g(2) 11. –f(4) + f(–4) 12. h(6)*[f(2)]2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-200714172012/85/9-the-basic-language-of-functions-87-320.jpg)