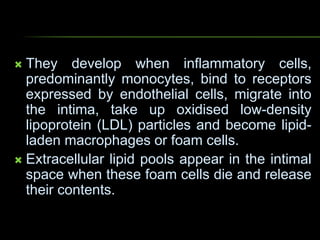

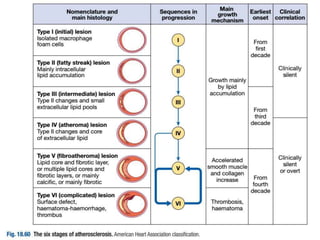

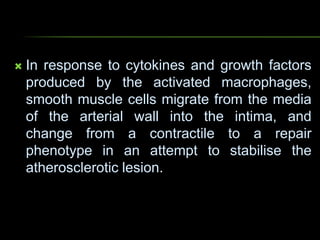

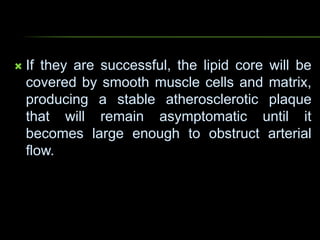

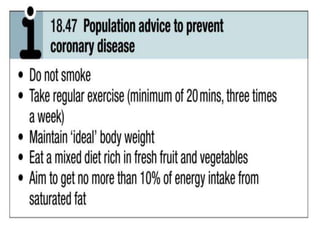

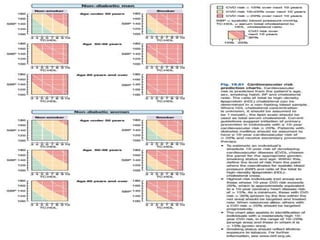

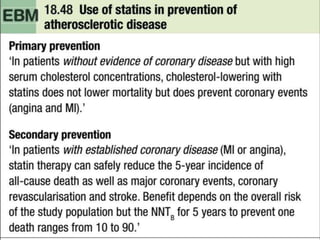

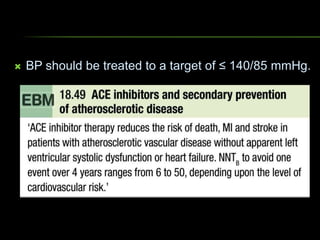

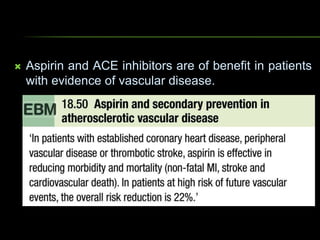

Atherosclerosis is a progressive inflammatory disease where fatty deposits called atheromas build up in the arteries. Over time it can restrict blood flow and cause complications like heart attacks or strokes. It begins early in life with fatty streaks in the arteries. Clinical symptoms often do not appear until later in life. Key risk factors include age, smoking, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, diabetes, obesity, lack of exercise, diet, stress, alcohol use, and family history. Both population-wide and targeted prevention strategies are used to modify risk factors and reduce the burden of atherosclerotic vascular disease.