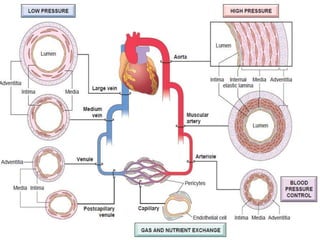

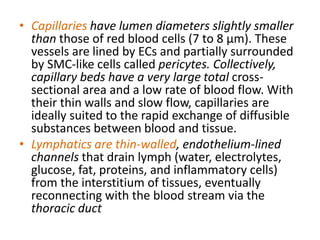

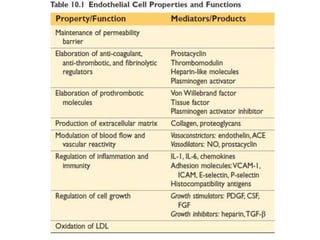

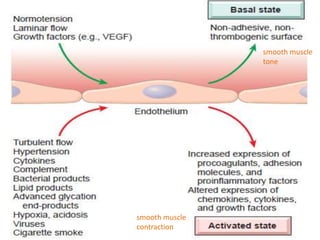

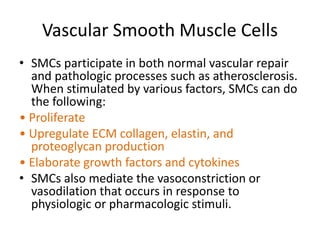

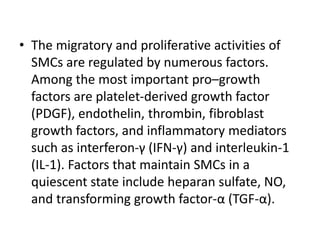

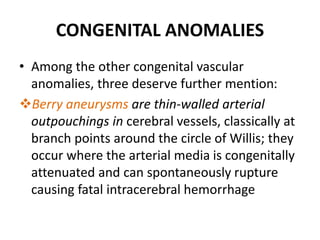

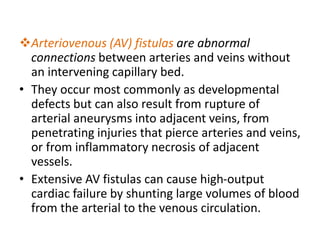

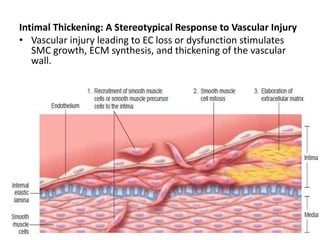

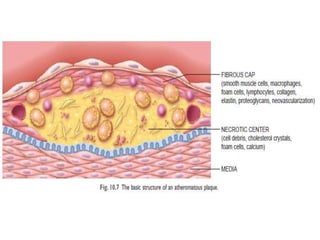

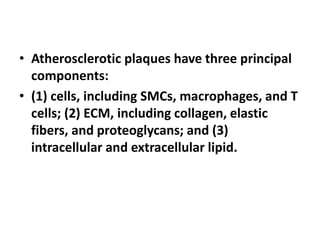

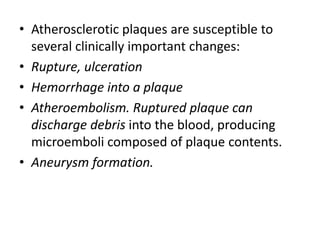

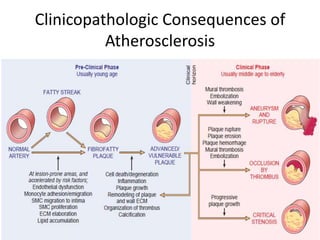

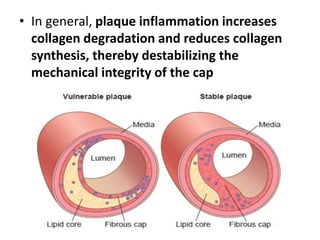

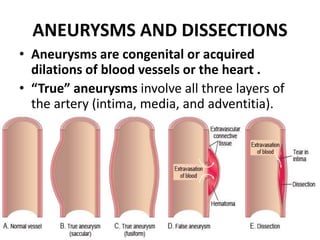

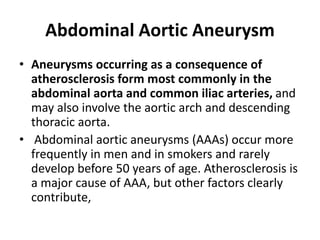

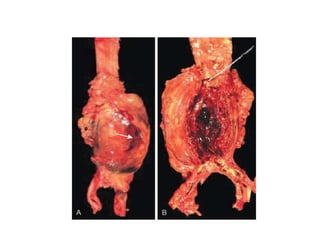

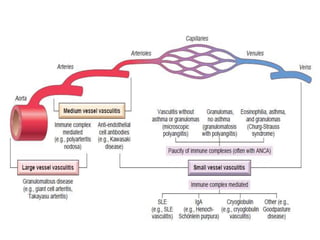

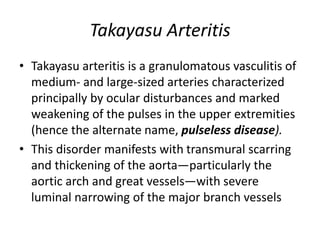

This document summarizes the structure and function of blood vessels. It discusses how blood vessels are composed of smooth muscle cells and extracellular matrix lined with endothelial cells. It describes the differences between arteries, veins, capillaries and how their structures relate to their functions. It also discusses vascular diseases like atherosclerosis, aneurysms, hypertension and vasculitis at a high level.