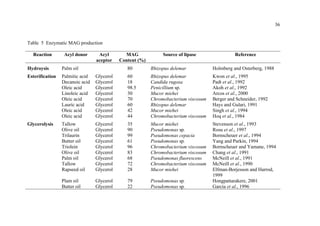

1. The document discusses monoacylglycerols (MAG) which are widely used as emulsifiers. They are currently produced through a high temperature chemical process using alkaline catalysts, which yields impurities and requires extensive purification.

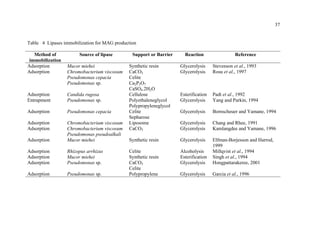

2. Biocatalysis using immobilized lipases is presented as a potential alternative that could produce MAG at ambient temperatures with less energy and in a more natural process. Various reactor configurations for continuous lipase-catalyzed MAG production are discussed.

3. The research aims to investigate continuous glycerolysis of palm olein for MAG production using immobilized lipase in suitable bioreactors and scale up the system. Palm olein is abundant and inexpensive in