1) The document describes a study that investigates the esterification of palm fatty acid distillate (PFAD) using a heterogeneous sulfonated microcrystalline cellulose catalyst and compares it to using sulfuric acid as the catalyst.

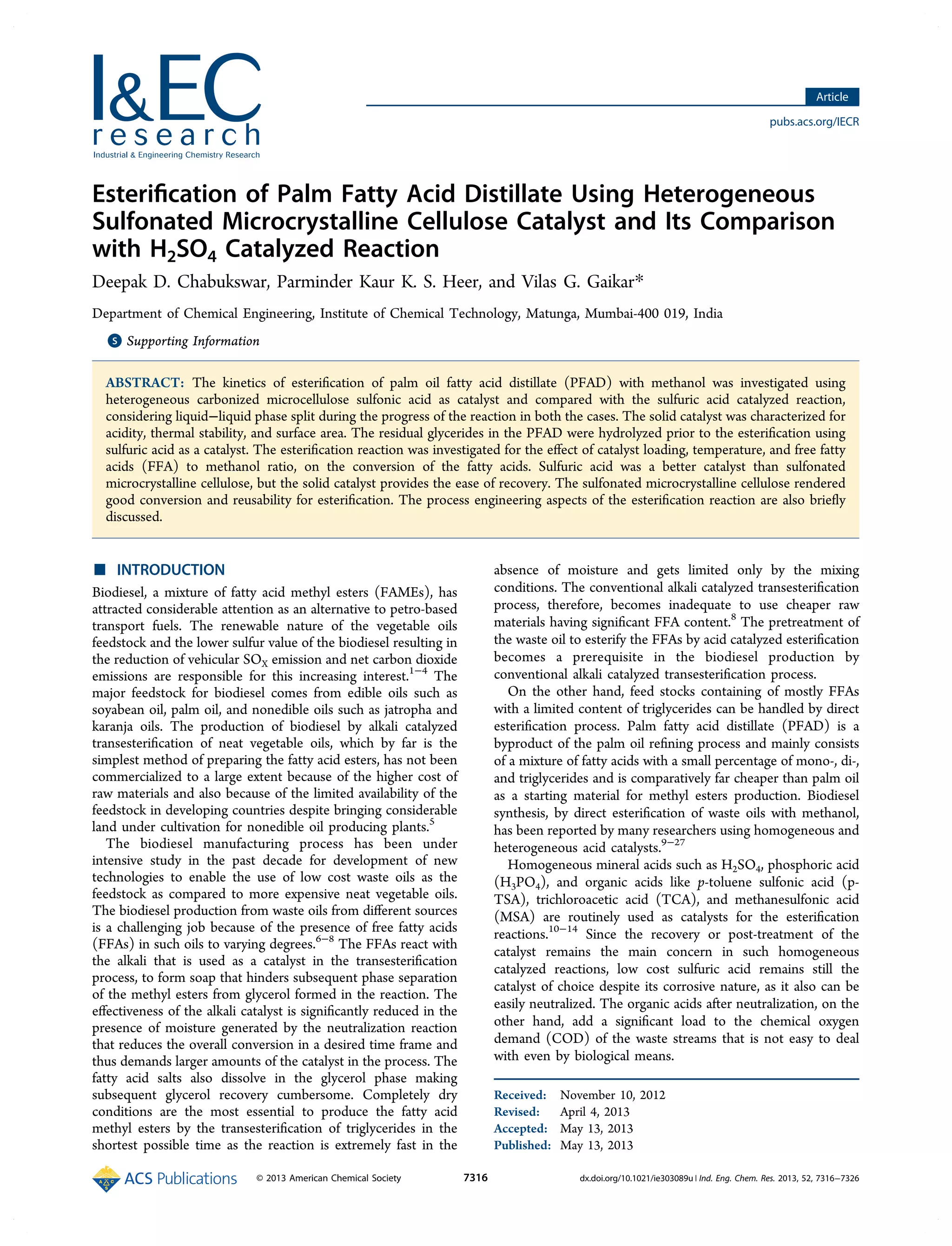

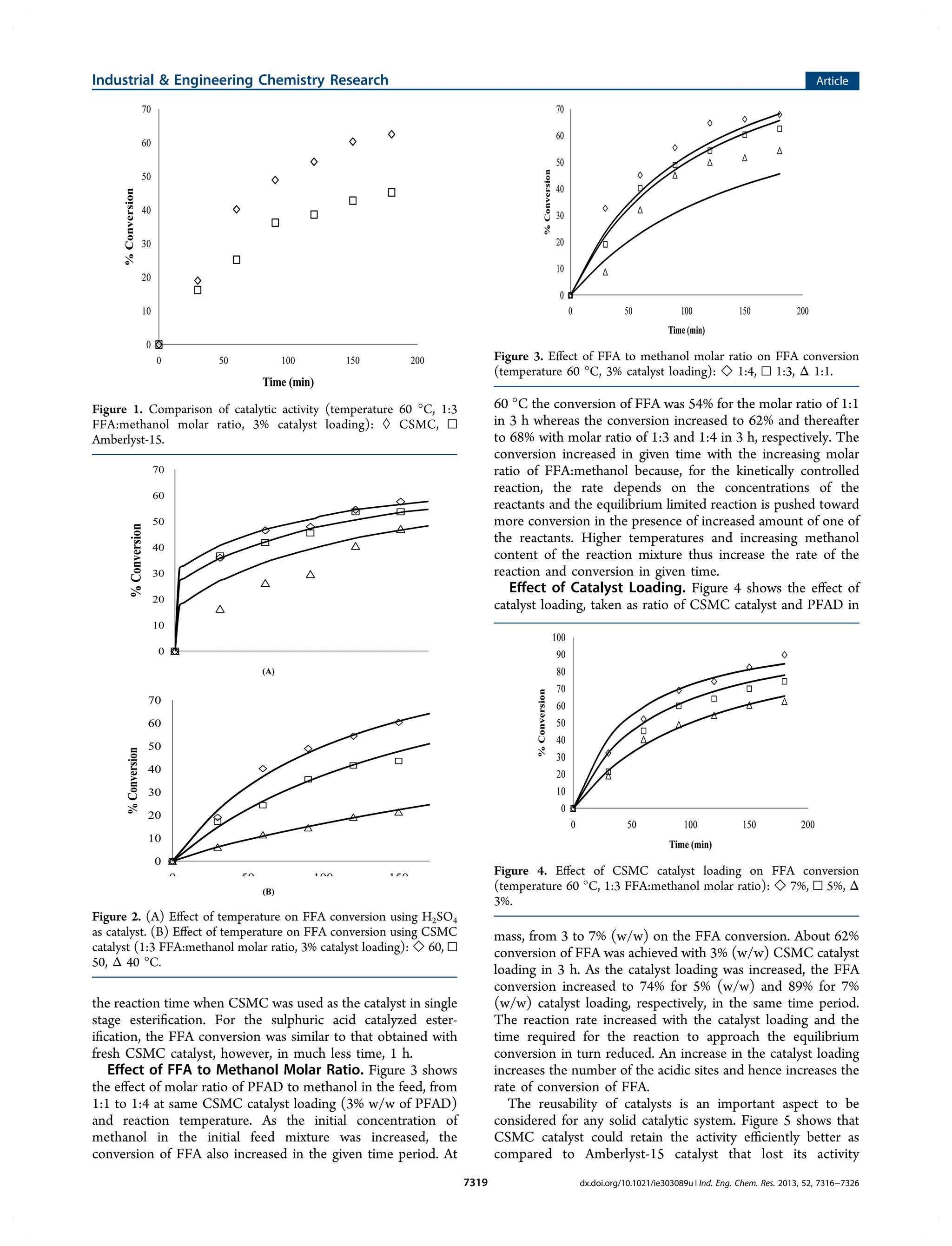

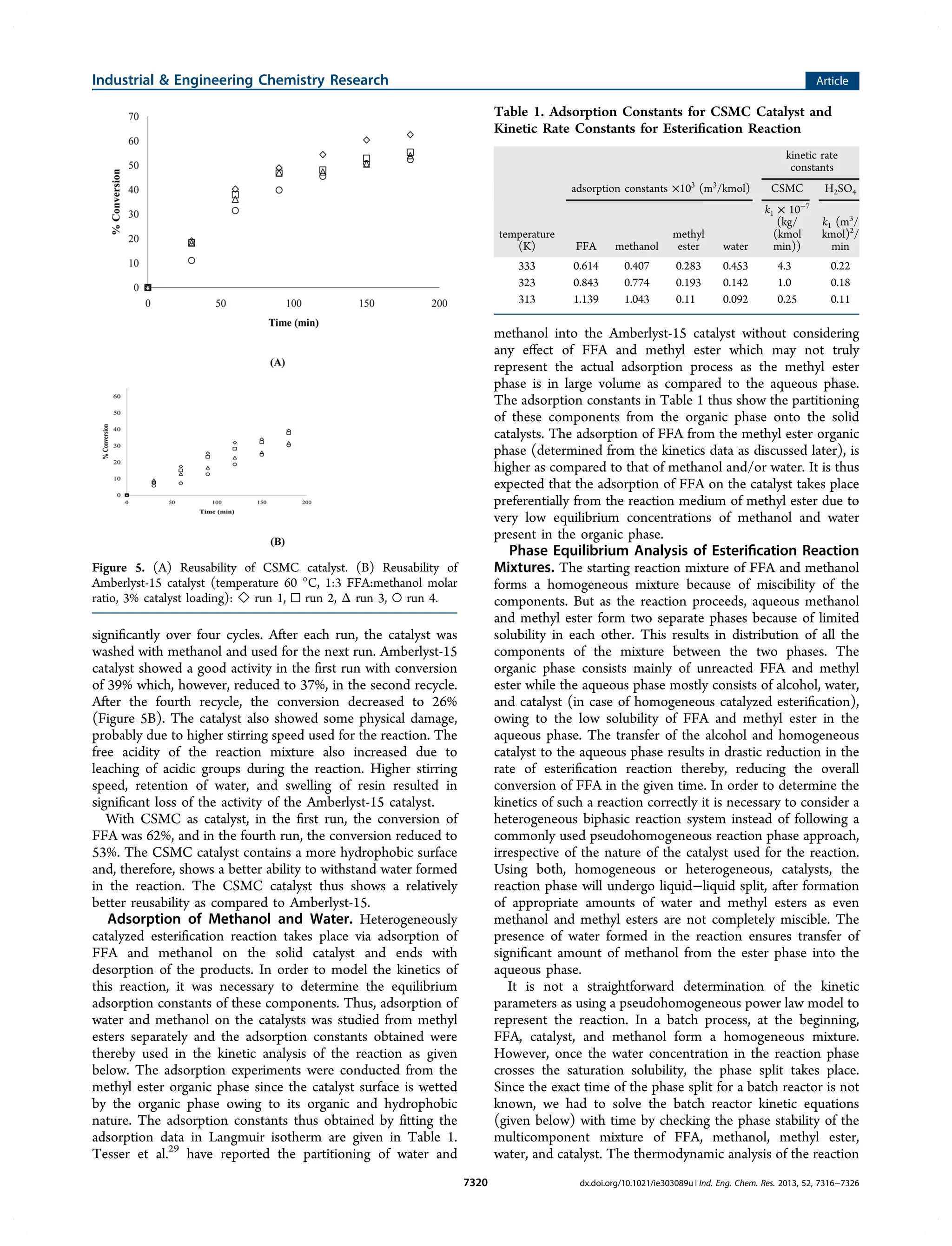

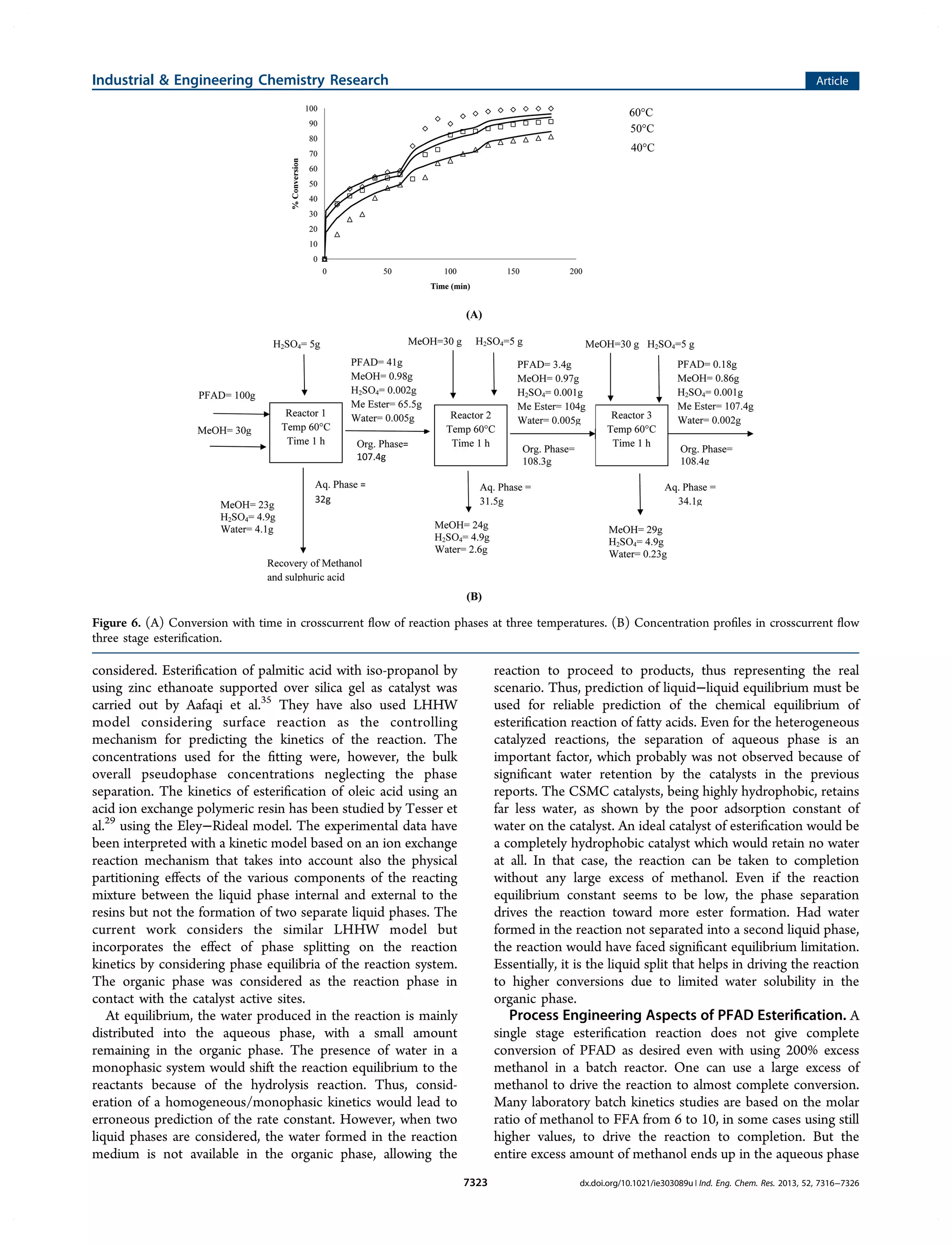

2) The solid catalyst was characterized and tested under various conditions of catalyst loading, temperature, and fatty acid to methanol ratio. Sulfuric acid performed better but the solid catalyst allows for easier recovery and reusability.

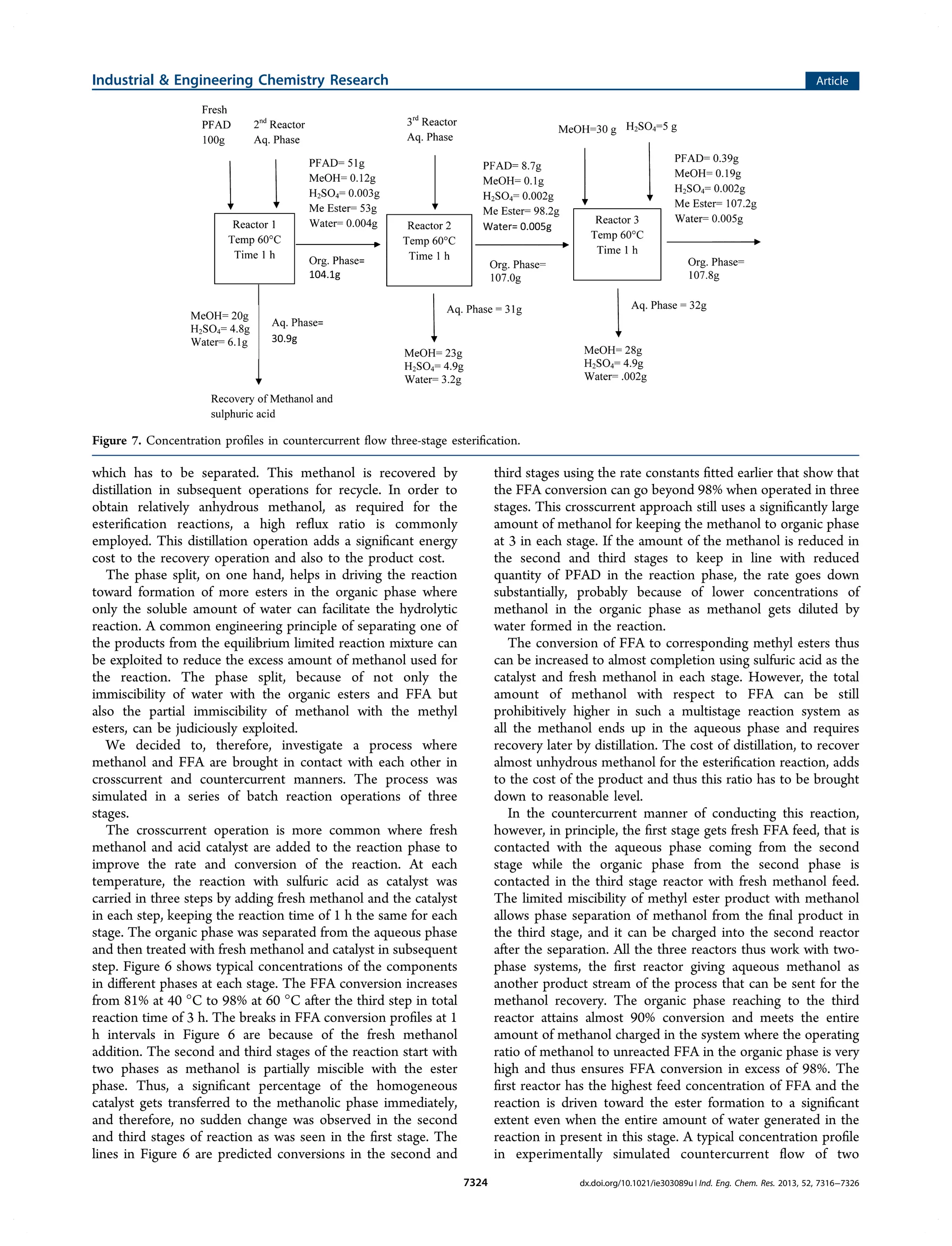

3) The kinetics of the esterification reaction were analyzed considering the biphasic liquid-liquid nature of the system that forms, with the two phases reaching equilibrium, in both catalyst systems.