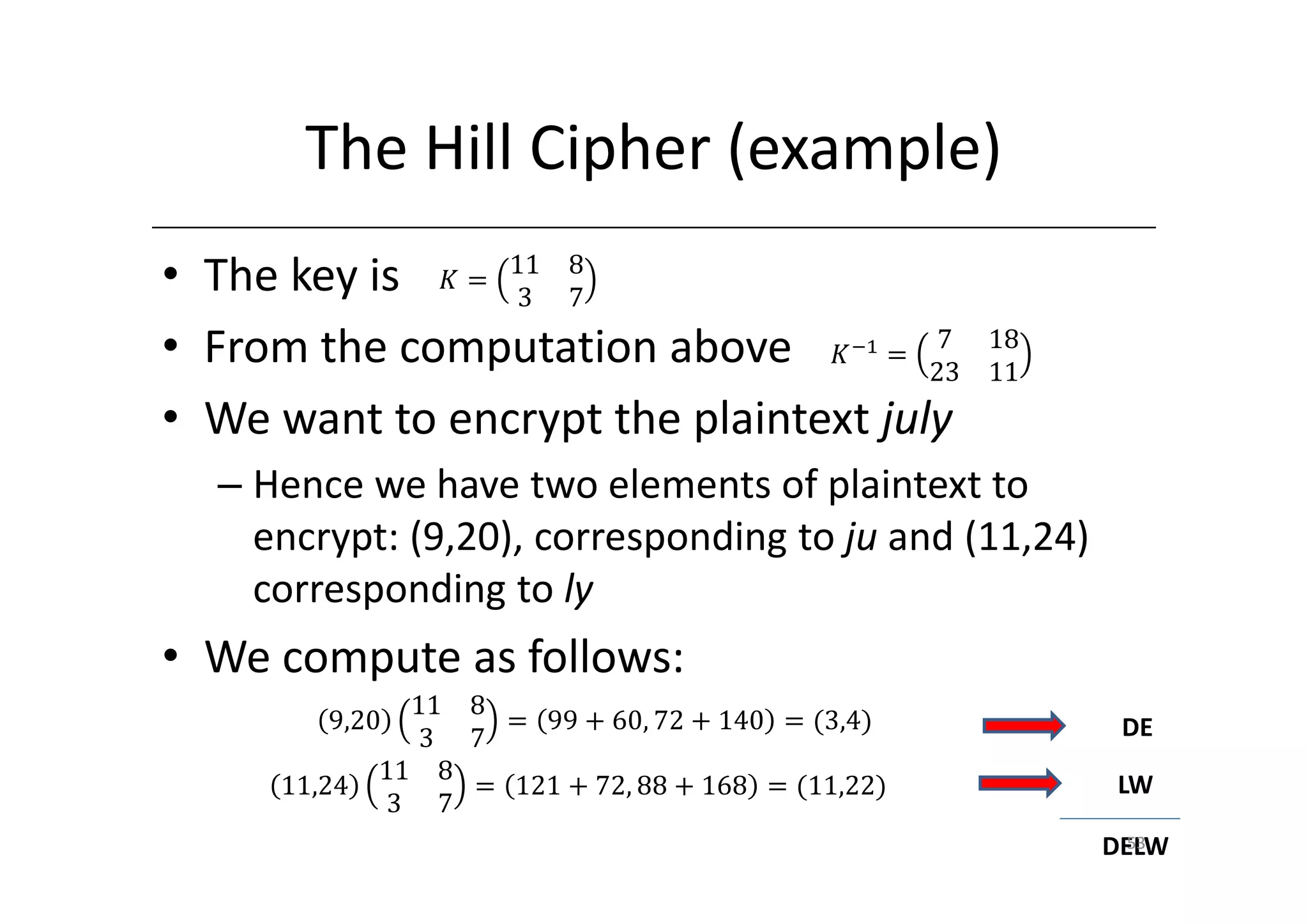

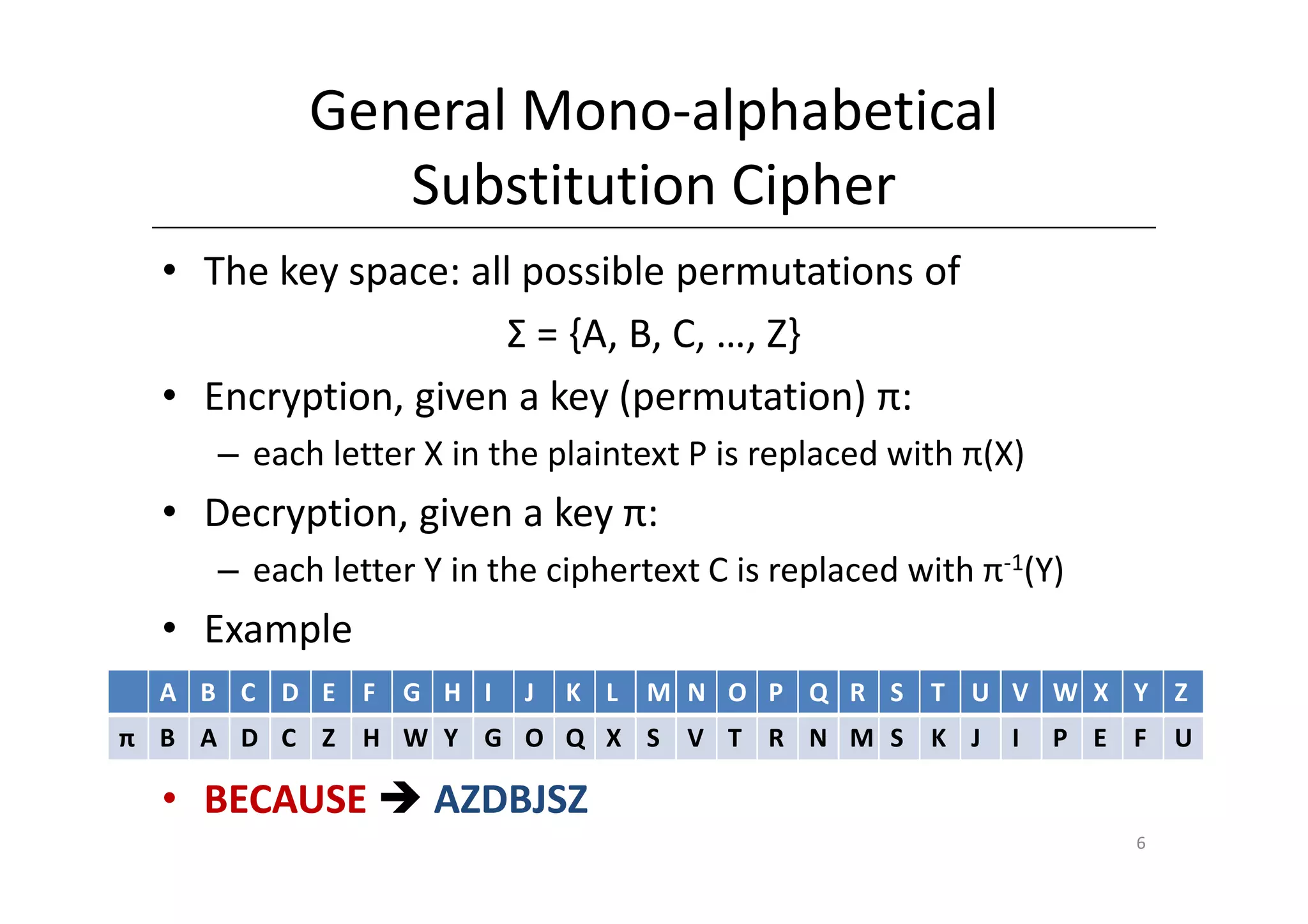

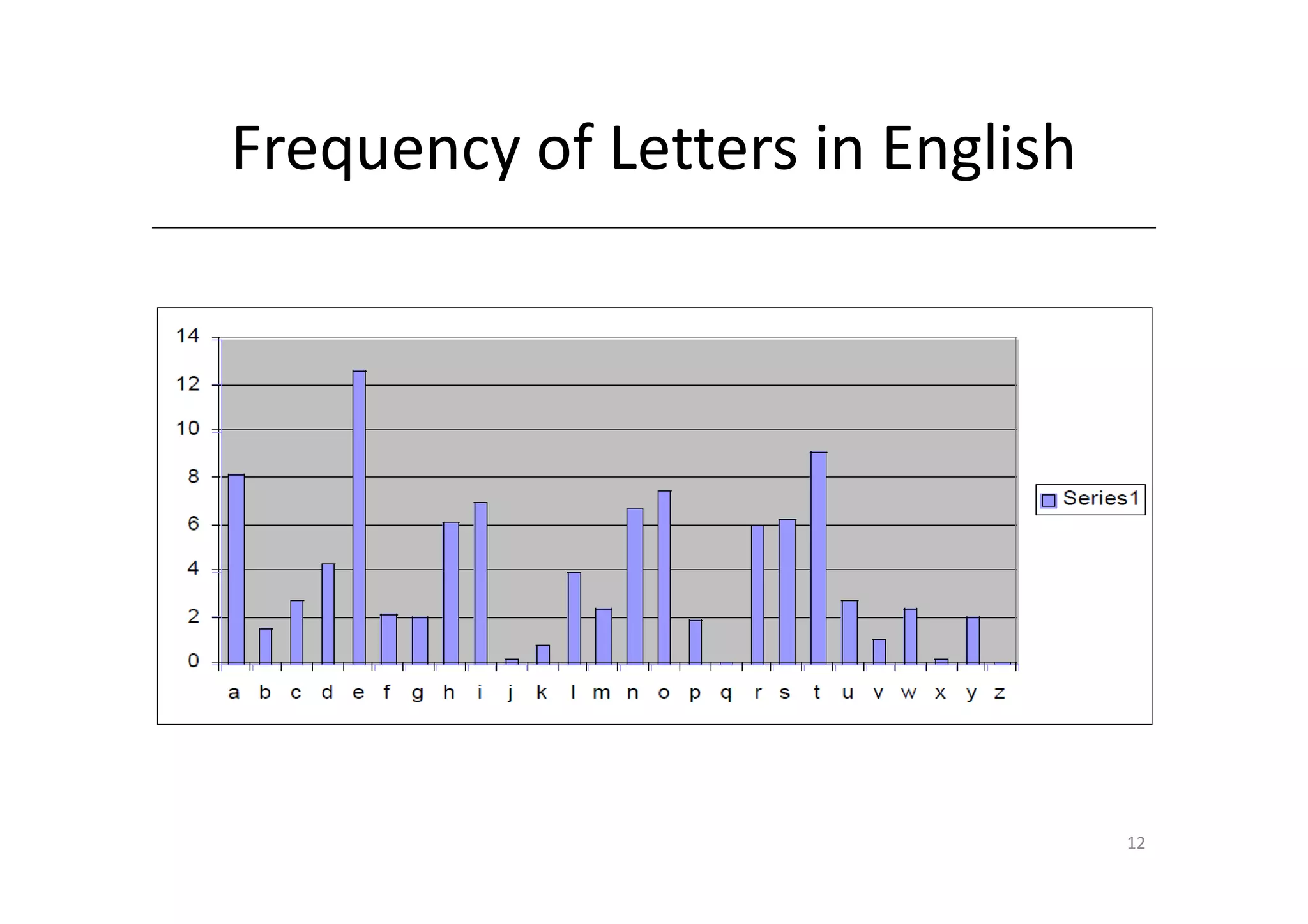

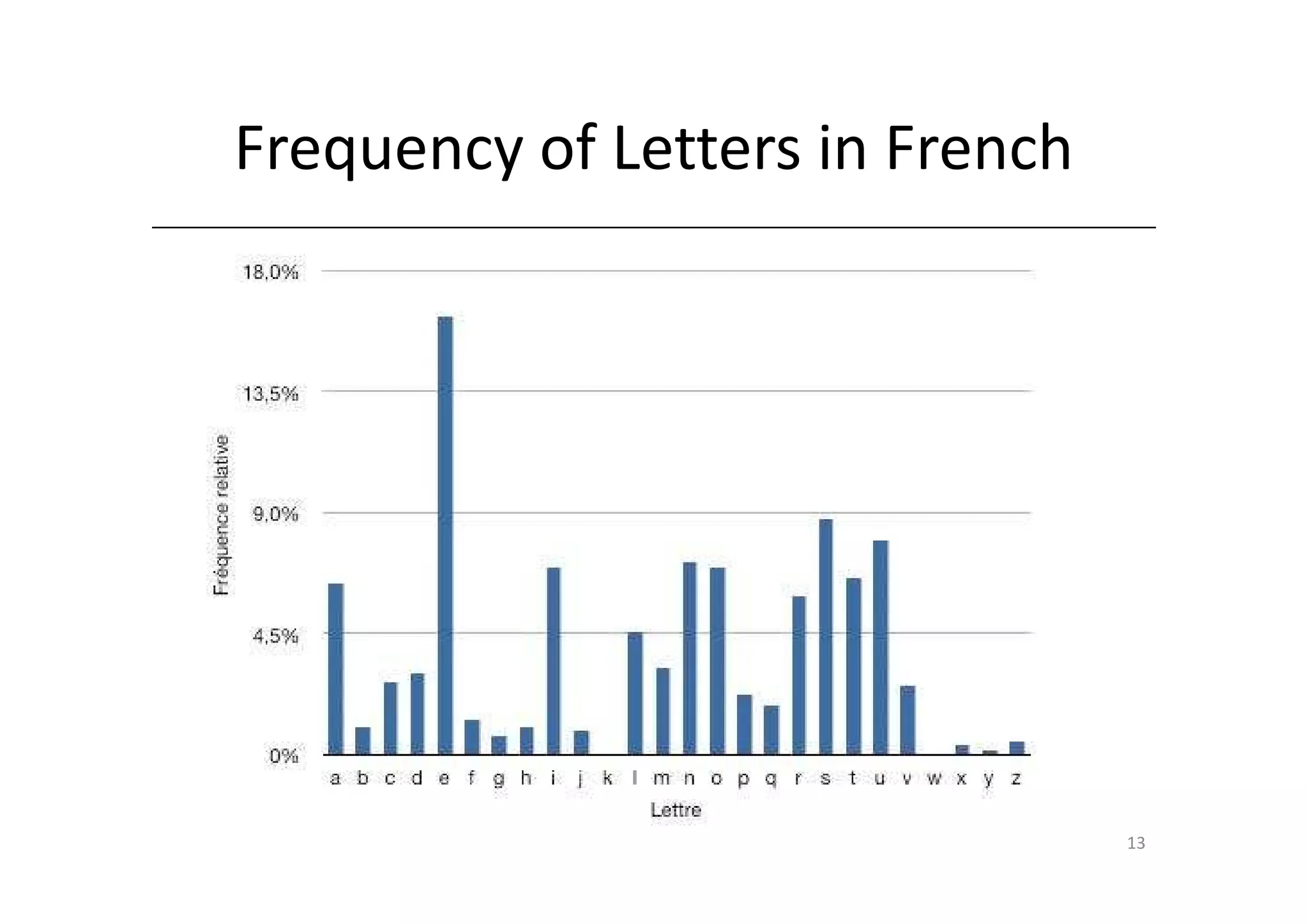

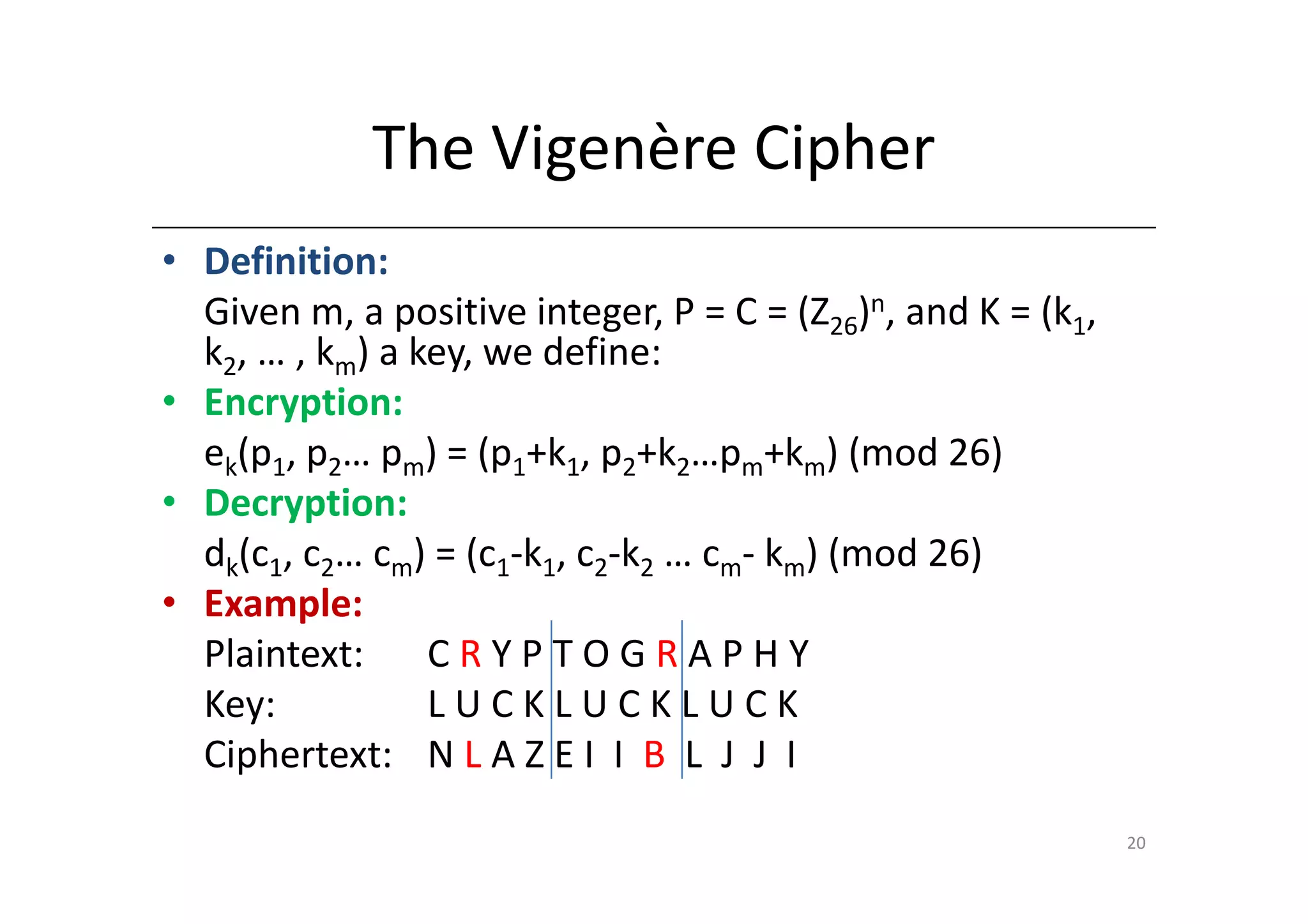

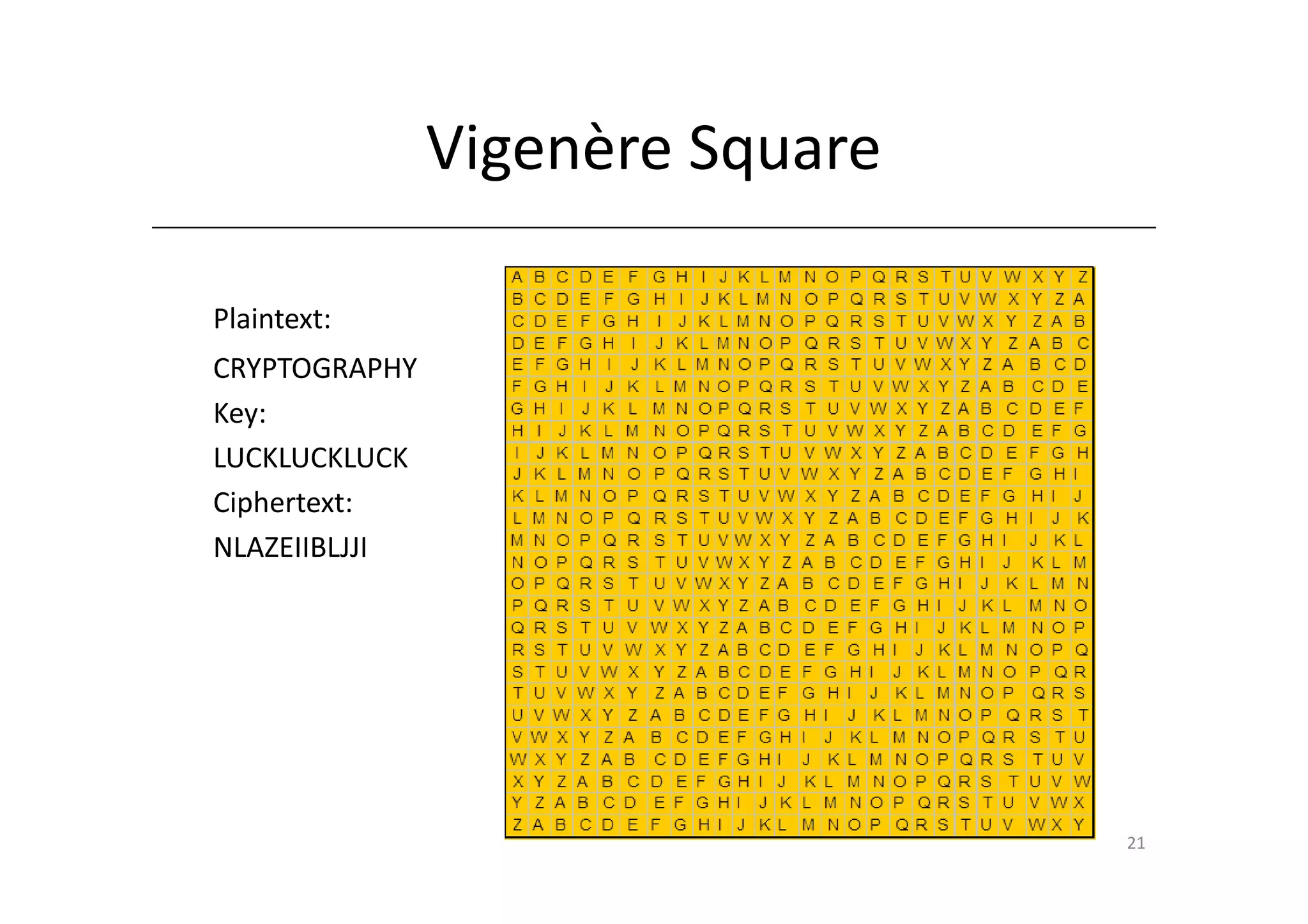

Shift ciphers are substitution ciphers where each letter is shifted a fixed number of positions in the alphabet. Substitution ciphers replace each letter with another letter or symbol according to a key. Frequency analysis involves analyzing letter frequencies in ciphertext to break substitution ciphers. The Vigenère cipher uses multiple substitution ciphers with different keys, making it harder to break using frequency analysis alone.

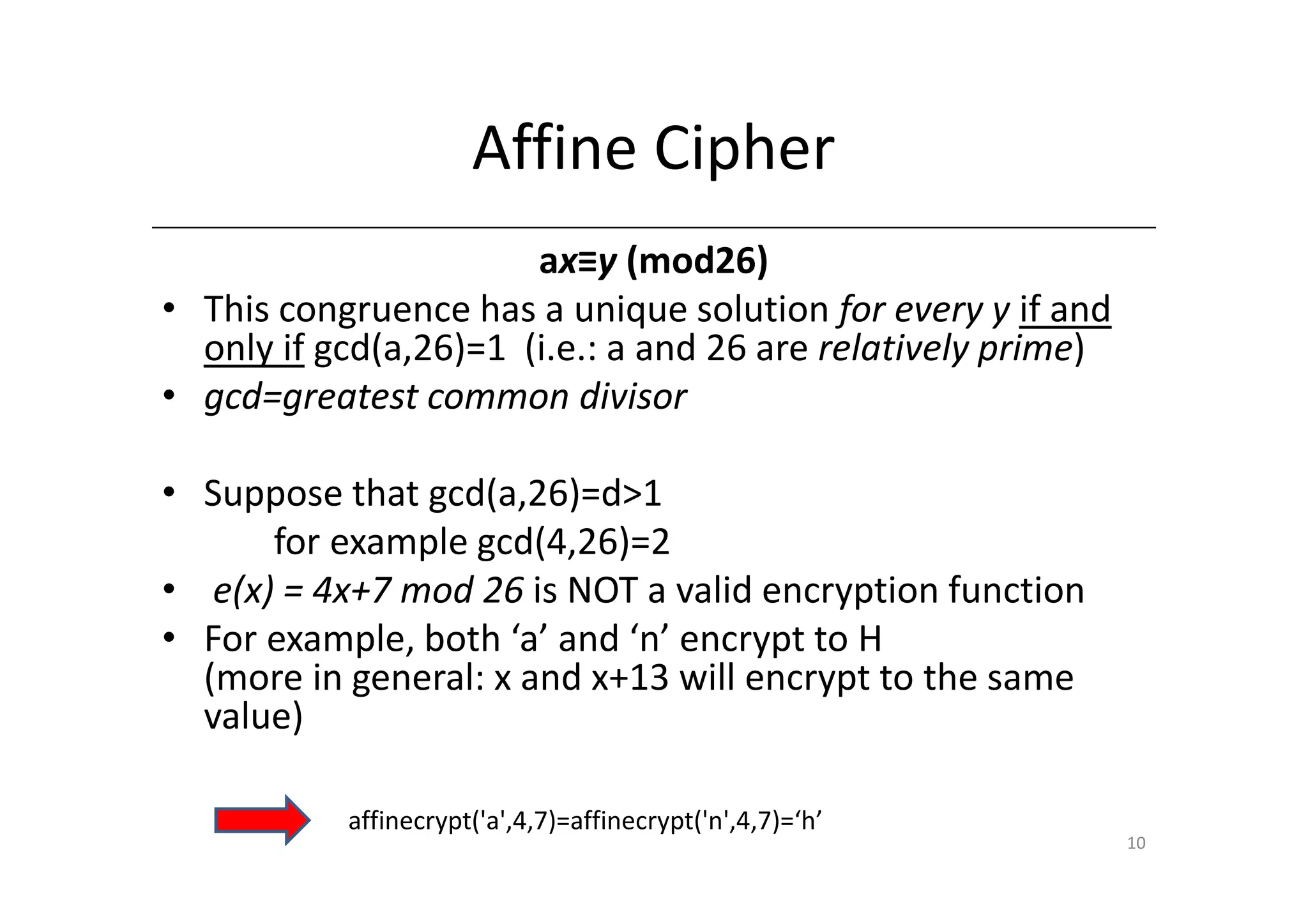

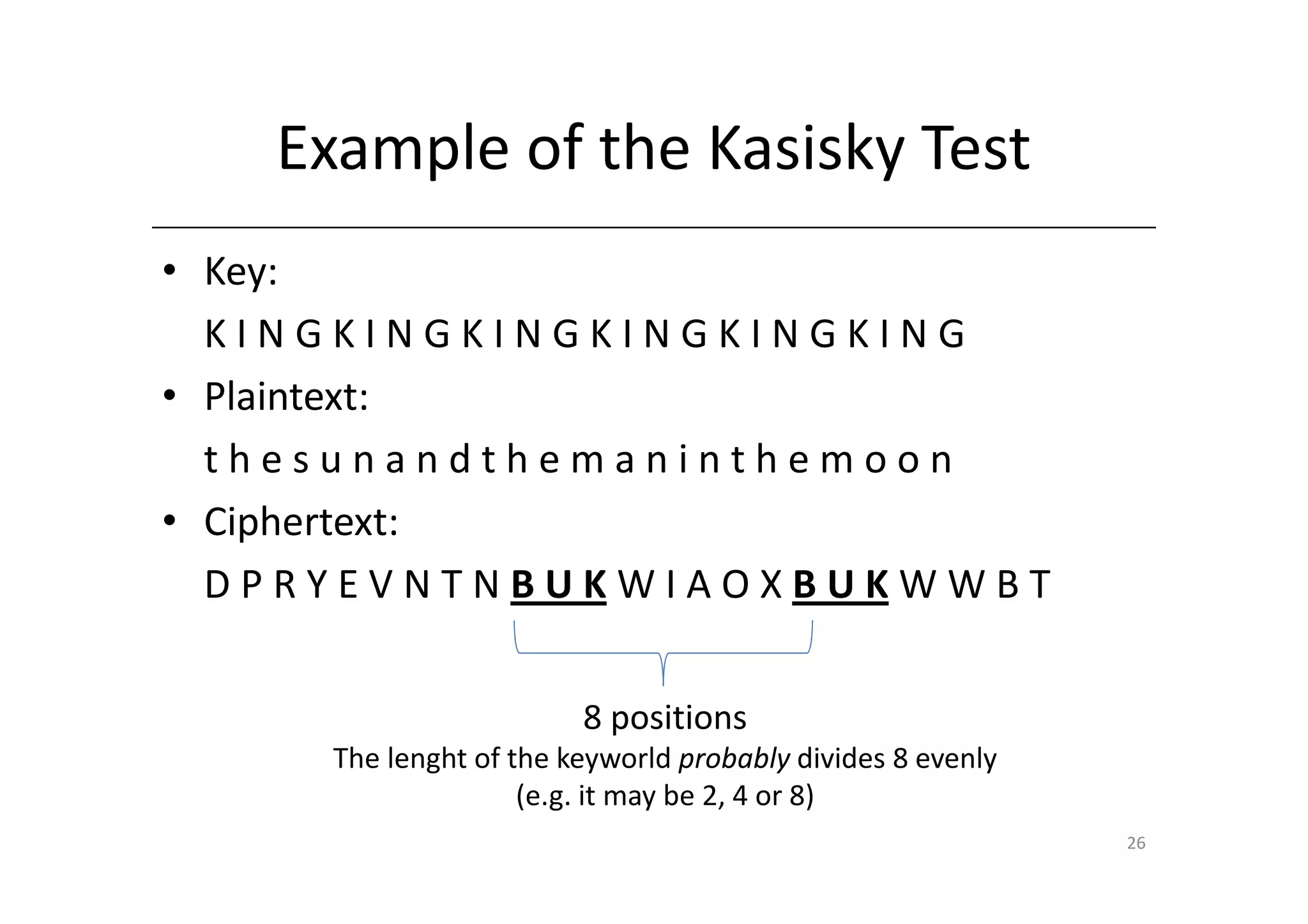

![Shift Cipher

• A Substitution Cipher

• The Key Space:

– [0 … 25]

• Encryption given a key K:

– each letter in the plaintext P is replaced with the K’th

letter following the corresponding number (shift

right)

• Decryption given K:

– shift left

• History: K = 3, Caesar’s cipher

2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-classicalcryptosystems-121219085001-phpapp01/75/2-classical-cryptosystems-2-2048.jpg)

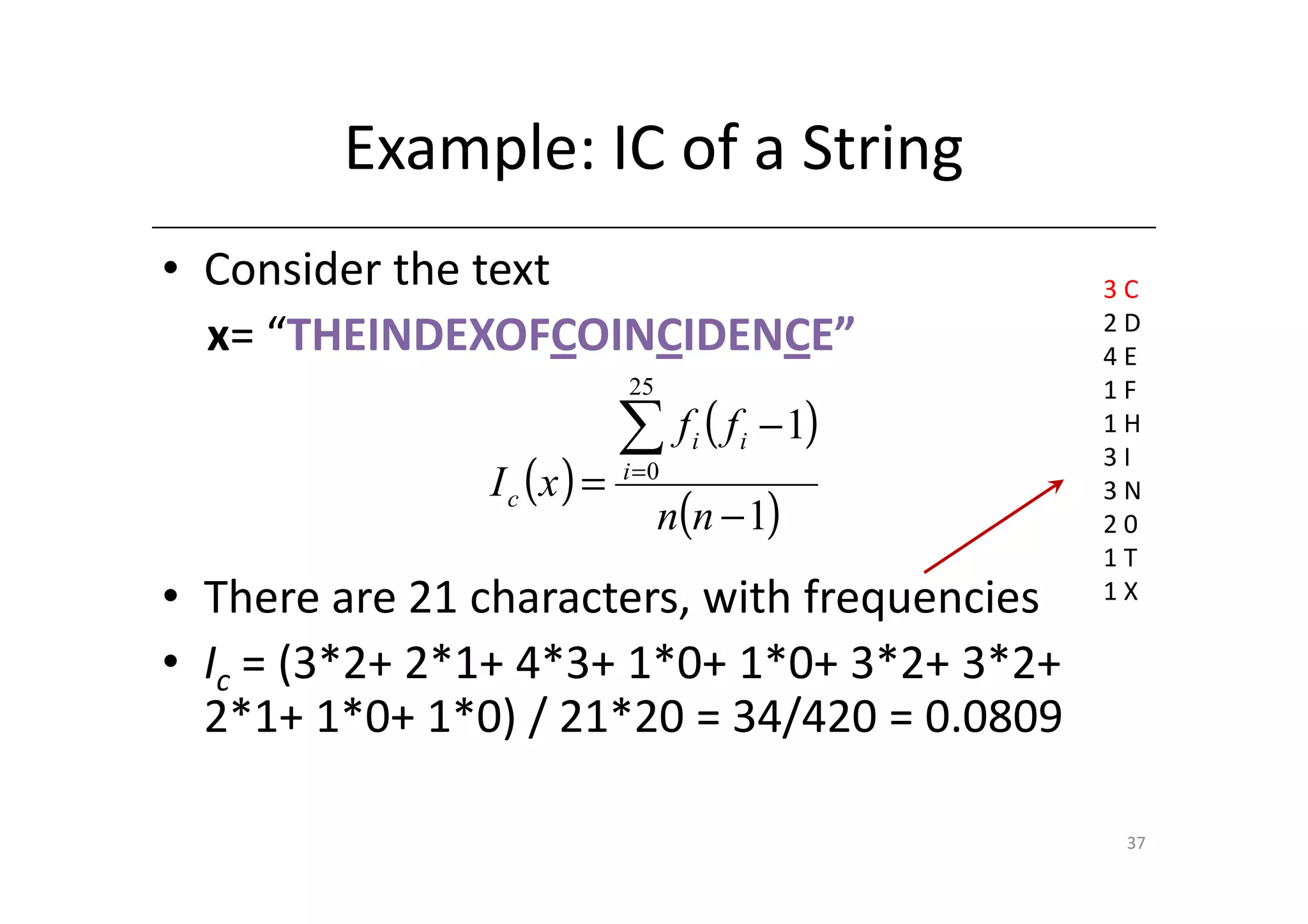

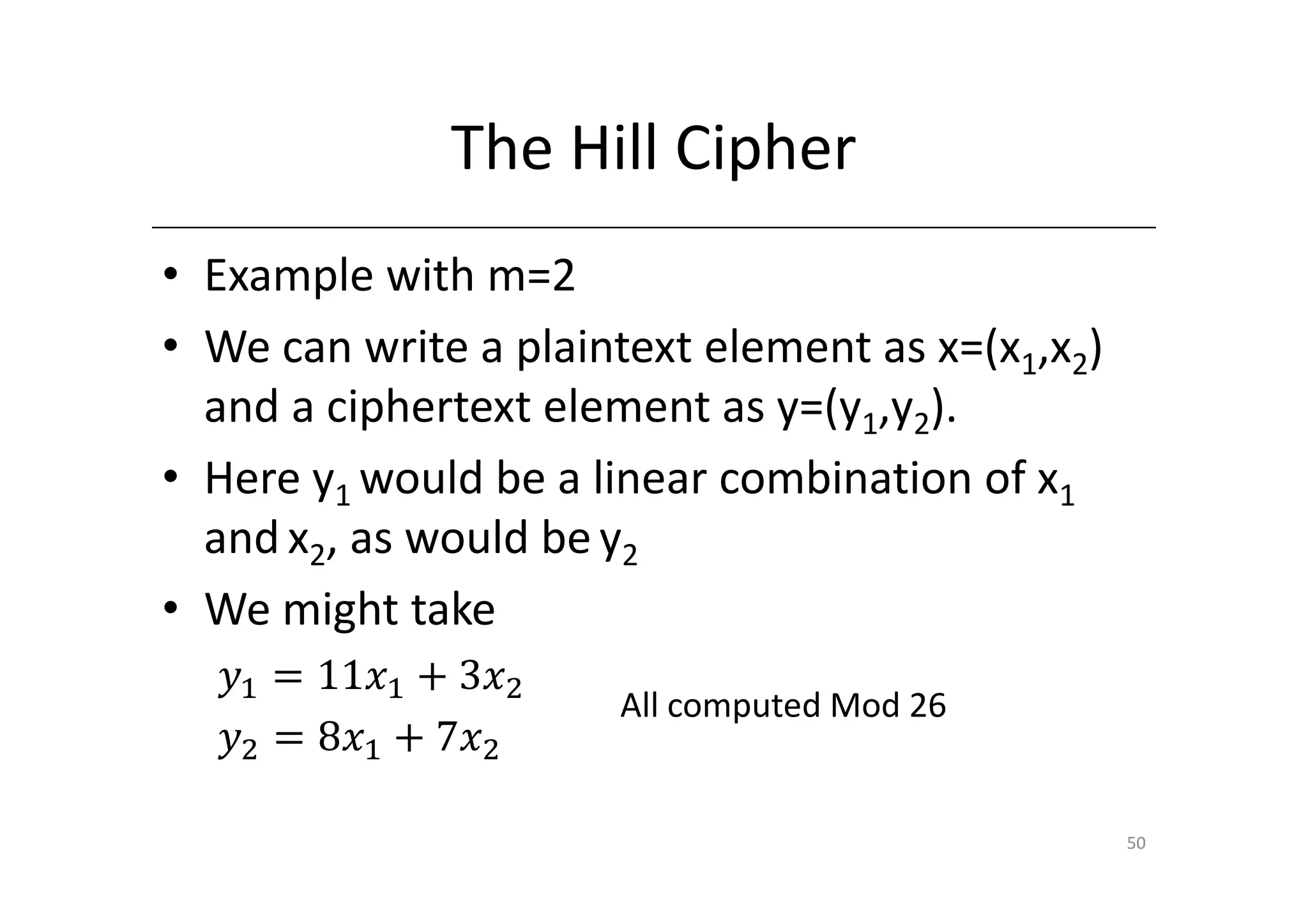

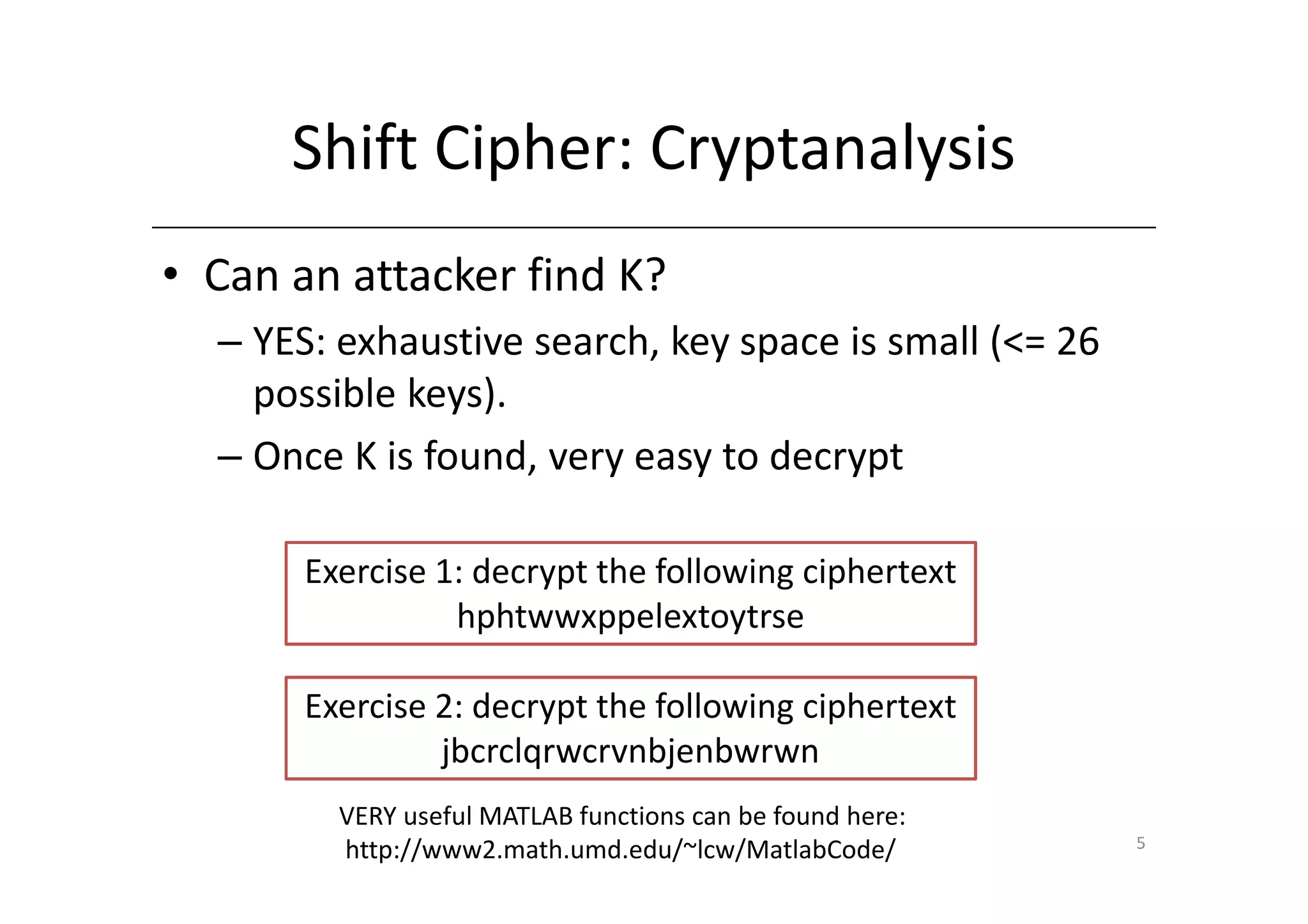

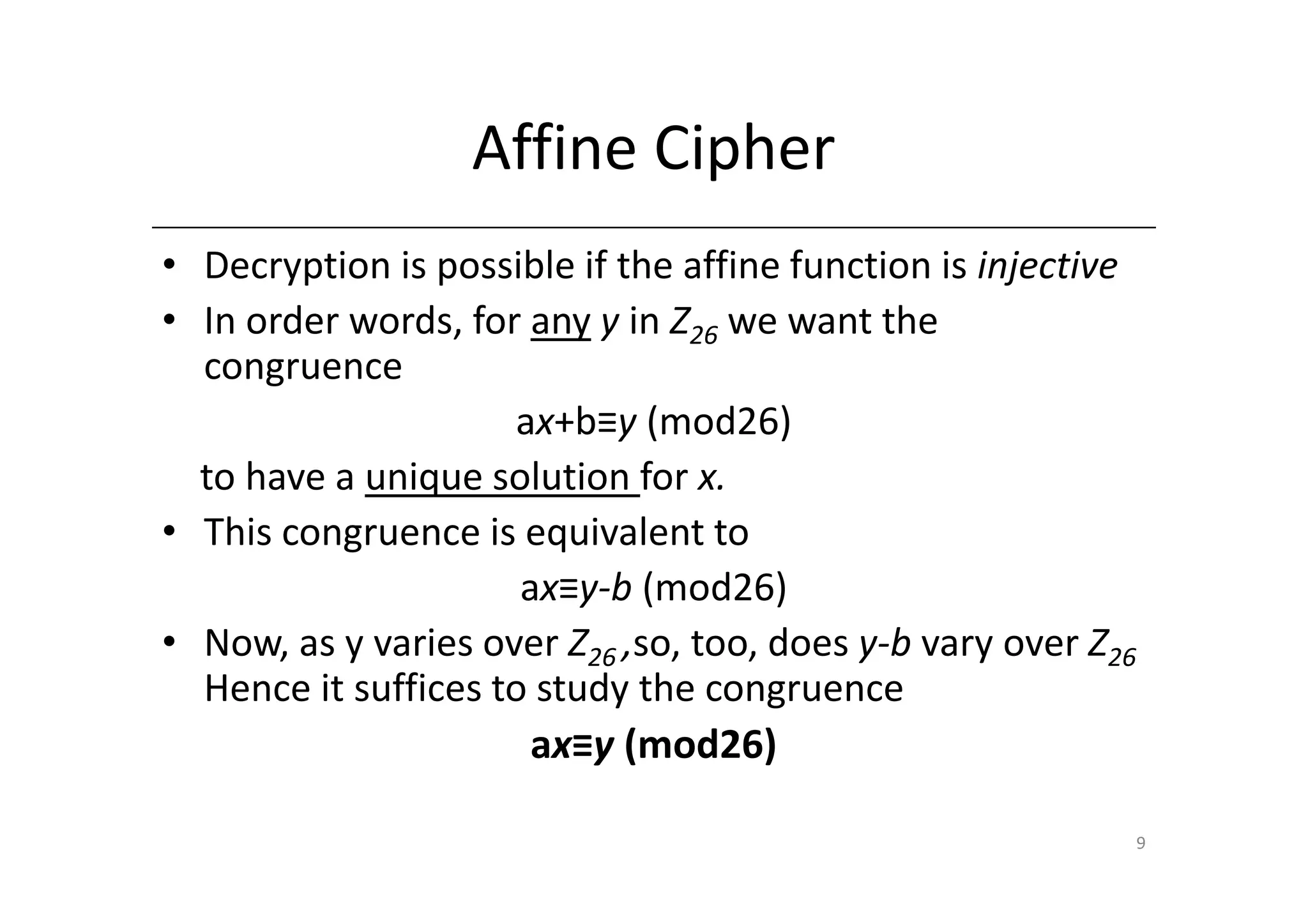

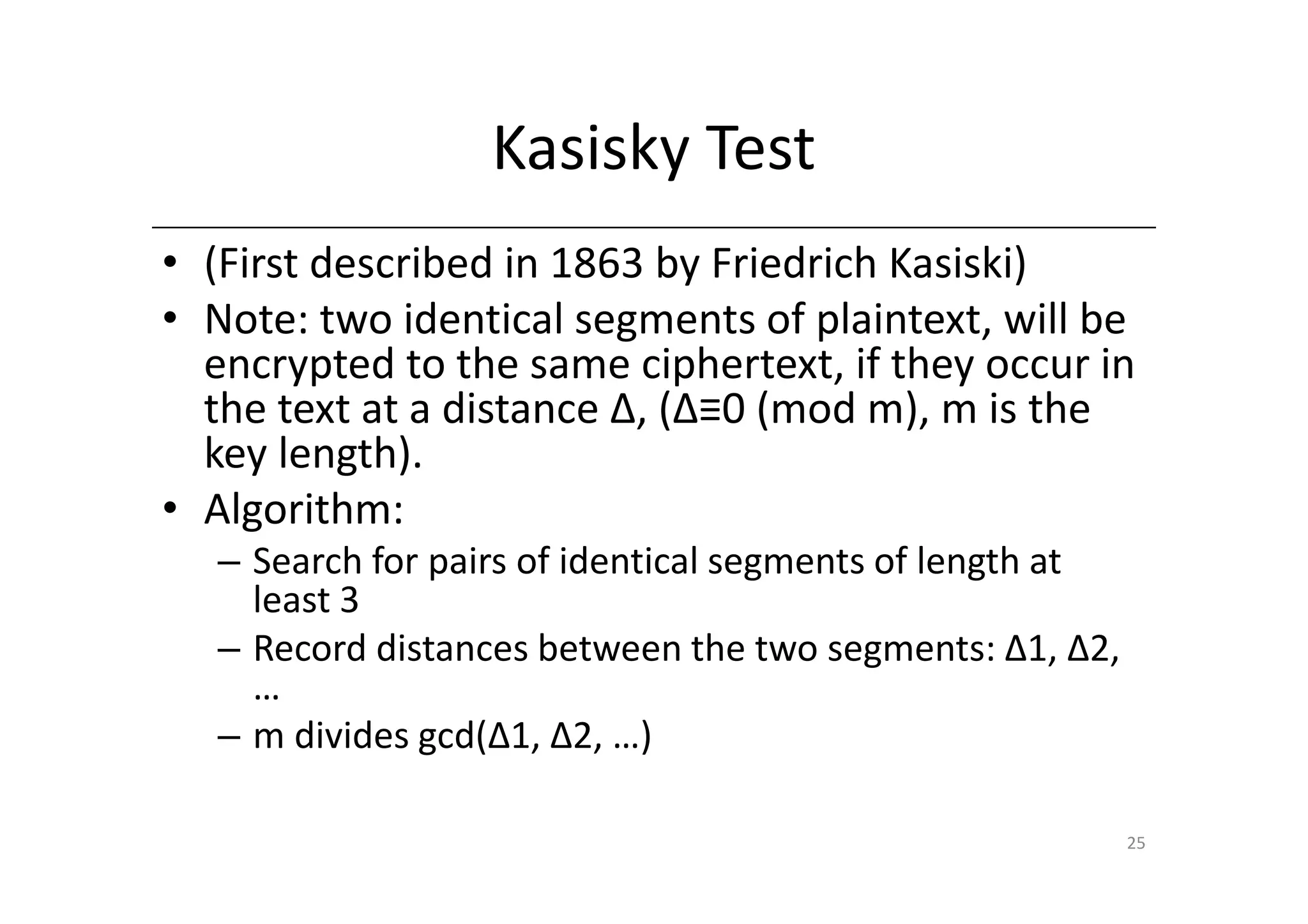

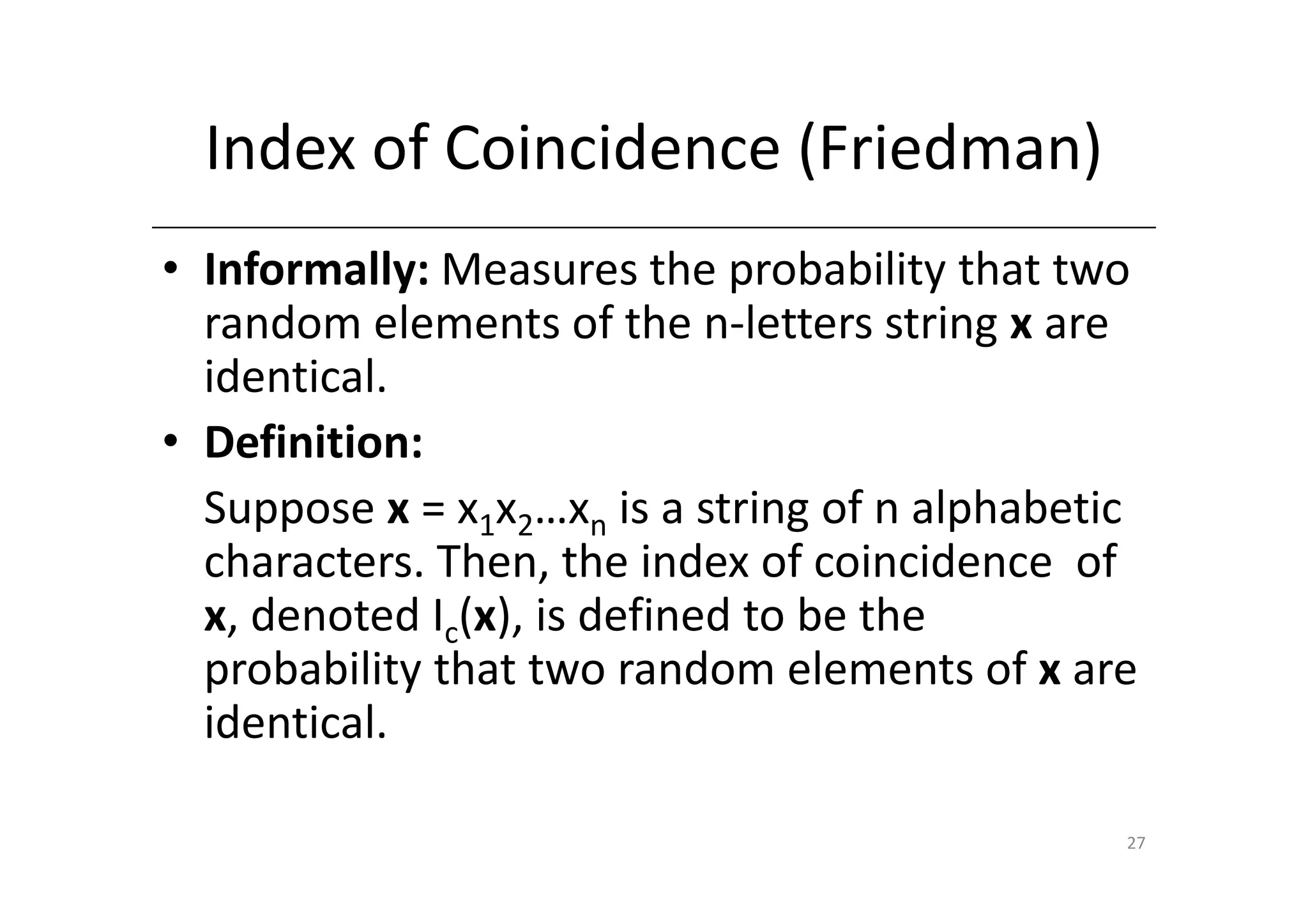

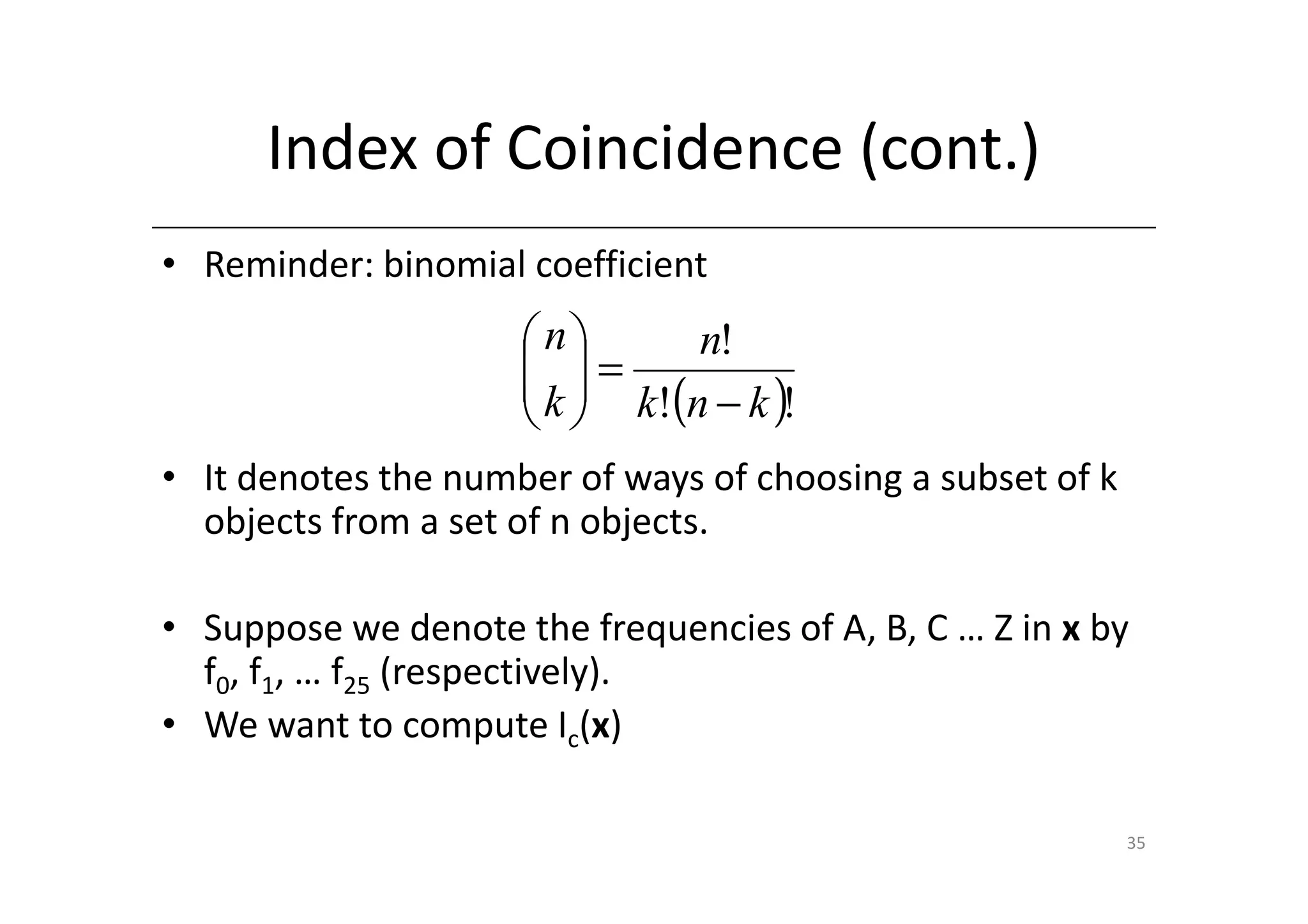

![Index of Coincidence (cont.)

• We can choose two elements of x (whose size is n) in

n Example: if n=3, nchoosek(3,2)=3; there are 3 ways of

ways.

2 choosing couples of n=3 items. Example: string ABC

fi

• For each i in [0…25], there are ways of choosing

2

both elements to be i. Hence we have the formula

25

fi 25

∑ 2

i =0 =

∑ f (f i i − 1)

I c (x ) = i =0

n n(n − 1)

2

36](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-classicalcryptosystems-121219085001-phpapp01/75/2-classical-cryptosystems-36-2048.jpg)