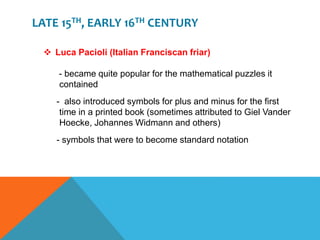

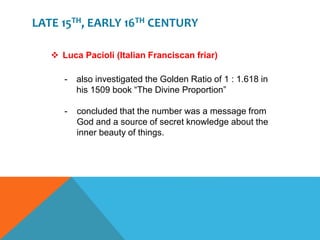

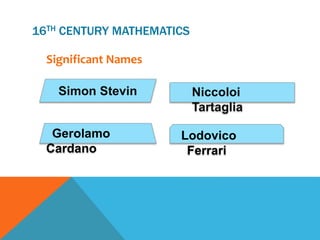

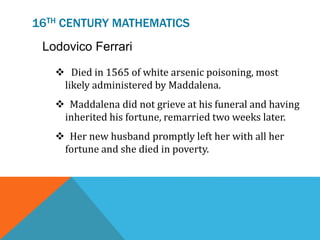

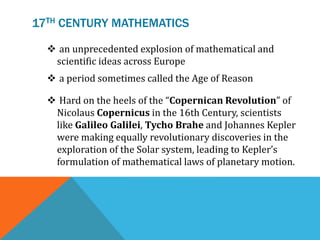

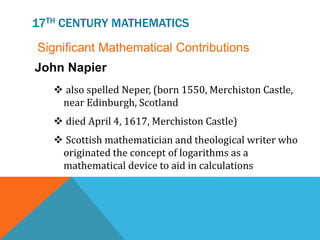

The document provides information about mathematics in the 16th and 17th centuries. It discusses key figures like Niccolò Tartaglia, Gerolamo Cardano, and Lodovico Ferrari who made advances in solving cubic and quartic equations in the 16th century. In the 17th century, important mathematicians included René Descartes who developed analytic geometry using Cartesian coordinates, and John Napier who originated the concept of logarithms. The document summarizes their main contributions which advanced mathematics and helped enable further scientific discoveries.

![17TH CENTURY MATHEMATICS

ISAAC NEWTON

Born December 25, 1642 [January 4, 1643, New

Style], Woolsthorpe, Lincolnshire, England

Died March 20 [March 31], 1727, London

Physicist, mathematician, astronomer, natural

philosopher, alchemist and theologian](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/16th-to-17th-renaissance-mathematics-221009080157-bc9fd5f3/85/16th-to-17th-Renaissance-mathematics-pptx-64-320.jpg)