Logarithms are mathematical functions that represent the exponent to which a base must be raised to produce a given number. They simplify complex calculations by turning multiplication into addition and division into subtraction. Logarithms find applications across various fields such as statistics, physics, and computer science.

![That is, the x-th power of b must equal y.[1][2]

The logarithm x is denoted logb(y). (Some European countries write b

log(y) instead.

[3]

) The number b is referred to as the base. For b = 2, for example, this means

since 23

= 2 · 2 · 2 = 8. The logarithm may be negative, for example

since

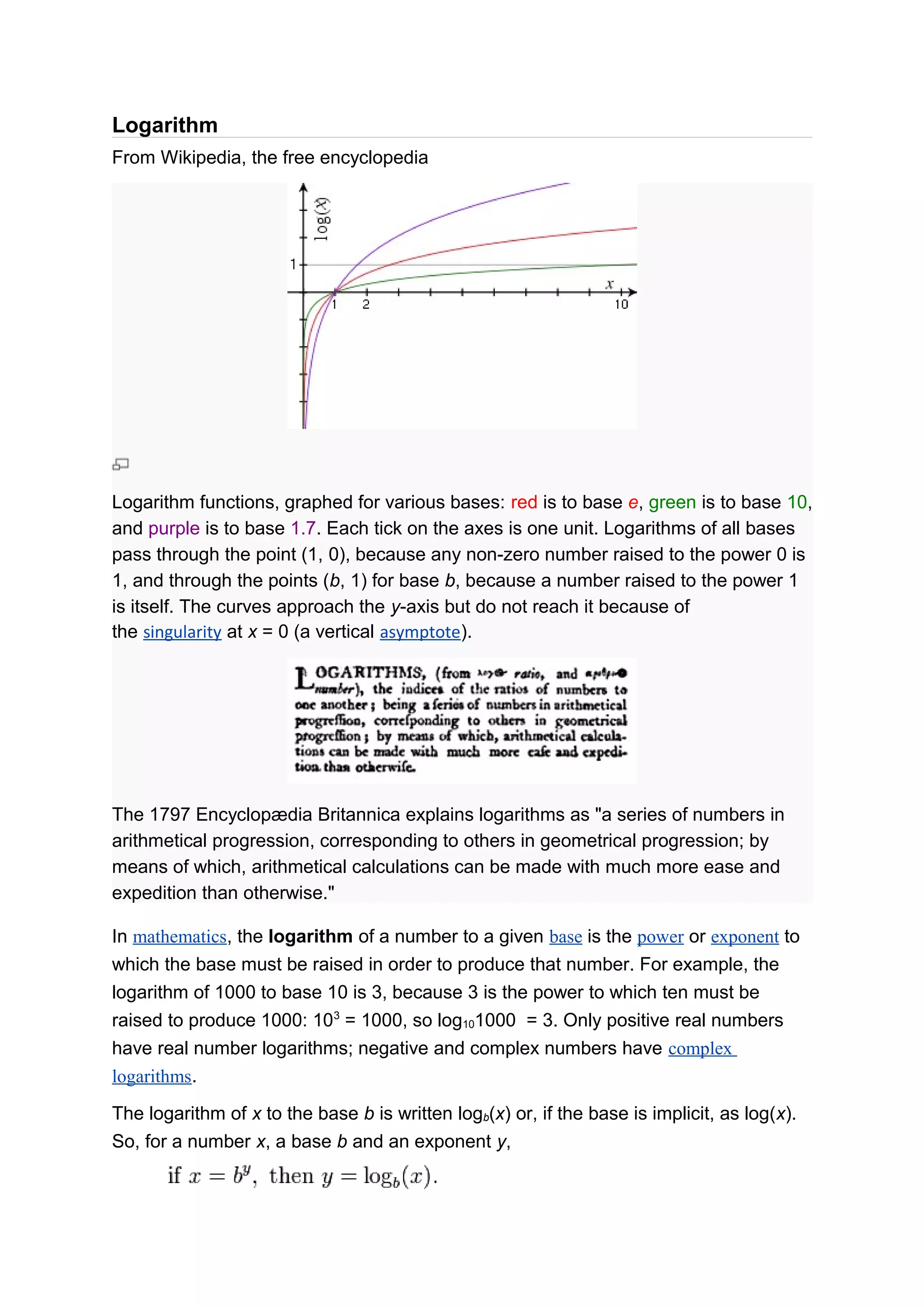

The right image shows how to determine (approximately) the logarithm. Given the

graph (in red) of the function f(x) = 2x

, the logarithm log2(y) is the For any given

number y (y = 3 in the image), the logarithm of y to the base 2 is the x-coordinate of

the intersection point of the graph and the horizontal line intersecting the vertical

axis at 3.

Above, the logarithm has been defined to be the solution of an equation. For this to

be meaningful, it is thus necessary to ensure that there is always exactly one such

solution. This is done using three properties of the function f(x) = bx

: in the case b >

1, this function f(x) is strictly increasing, that is to say, f(x) increases when x does so.

Secondly, the function takes arbitrarily big values and arbitrarily small positive

values. Thirdly, the function is continuous. Intuitively, the function does not "jump": the

graph can be drawn without lifting the pen. These properties, together with

the intermediate value theorem ofelementary calculus ensure that there is indeed exactly

one solution x to the equation

f(x) = bx

= y,

for any given positive y. When 0 < b < 1, a similar argument is used, except that f(x)

= bx

is decreasing in that case.

[edit]Identities

Main article: Logarithmic Identities

The above definition of the logarithm implies a number of properties.

[edit]Logarithm of products

Logarithms map multiplication to addition. That is to say, for any two positive real

numbers x and y, and a given positive base b, the identity

logb(x · y) = logb(x) + logb(y).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1557-logarithm-161031144101/85/1557-logarithm-3-320.jpg)