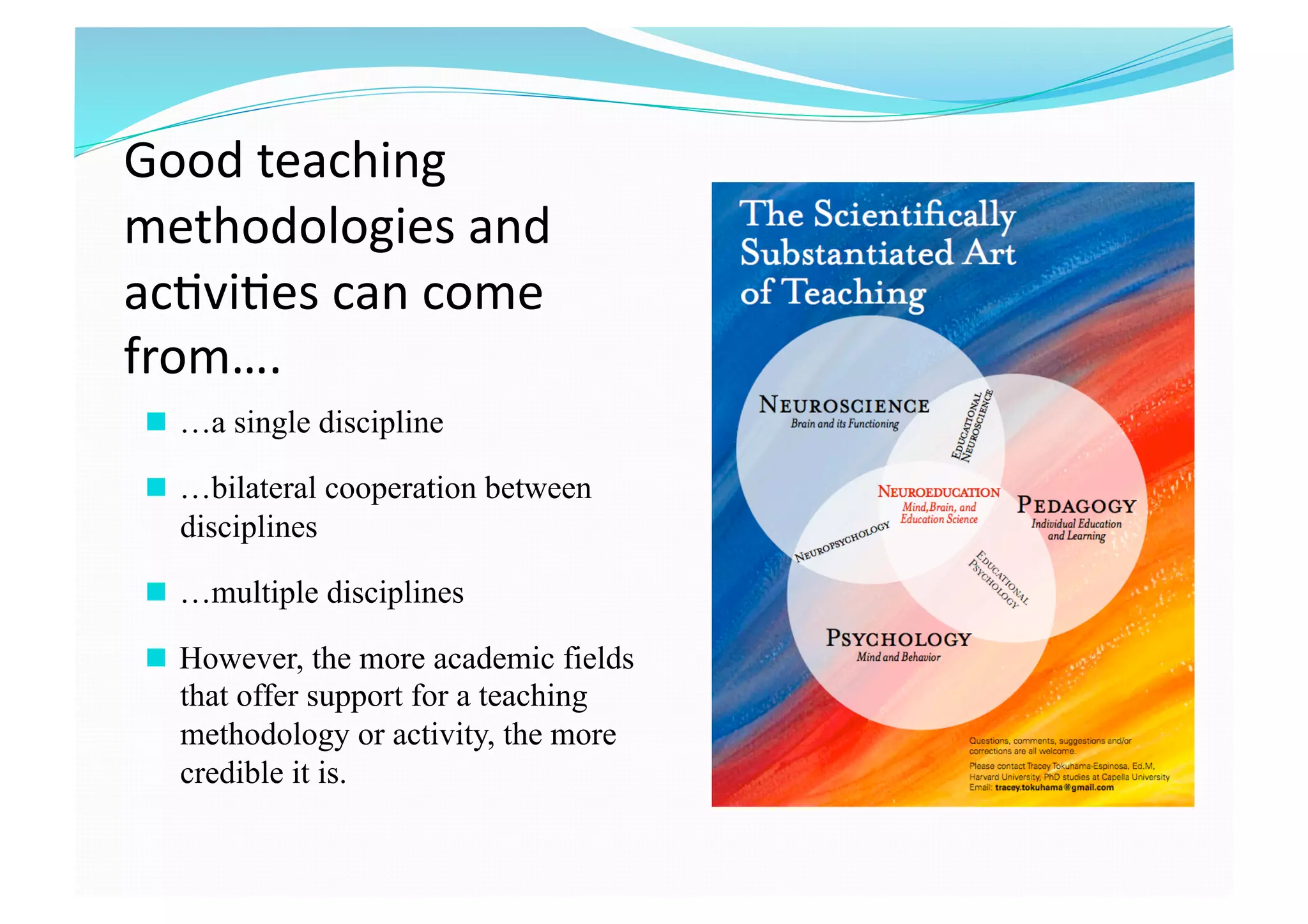

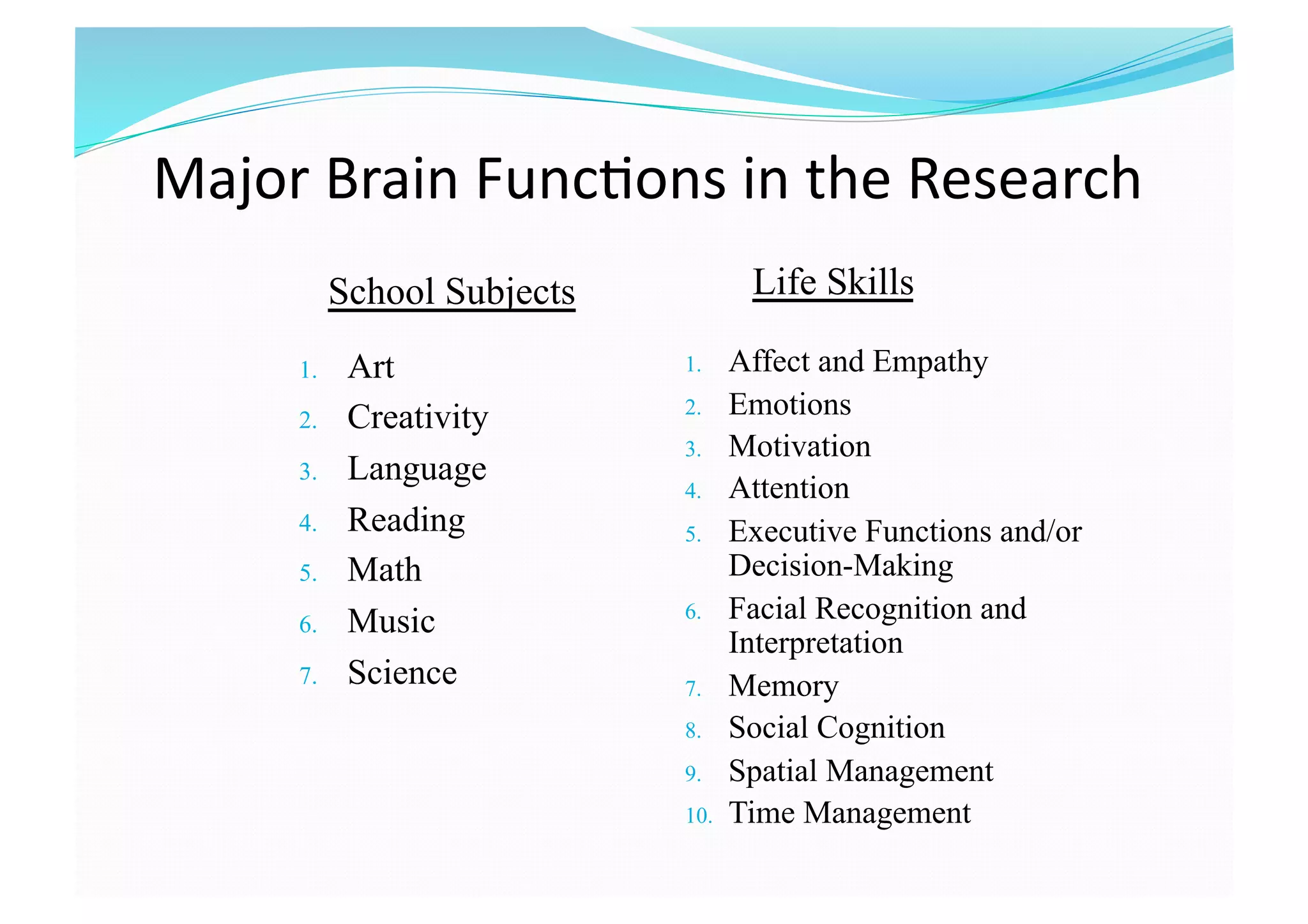

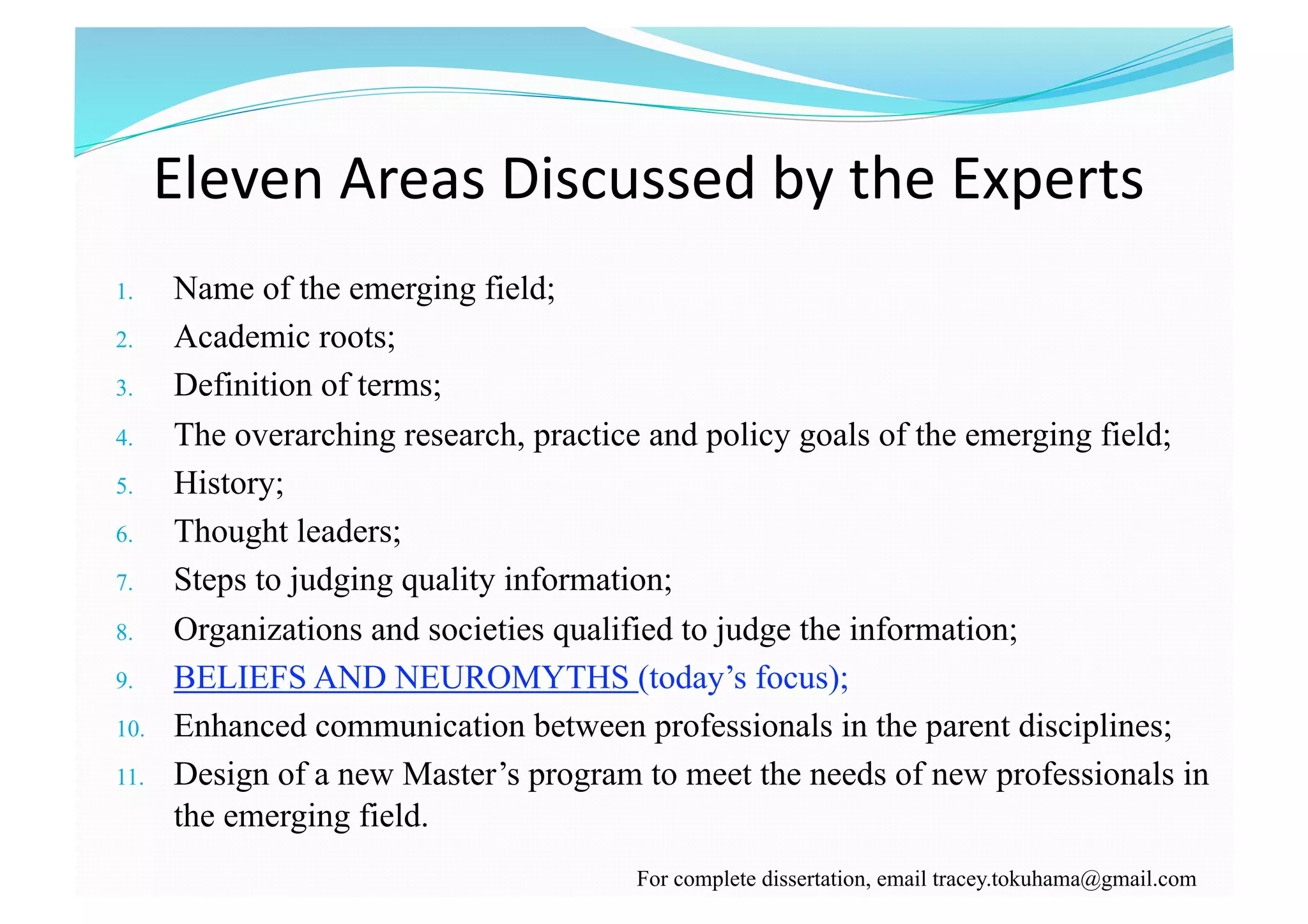

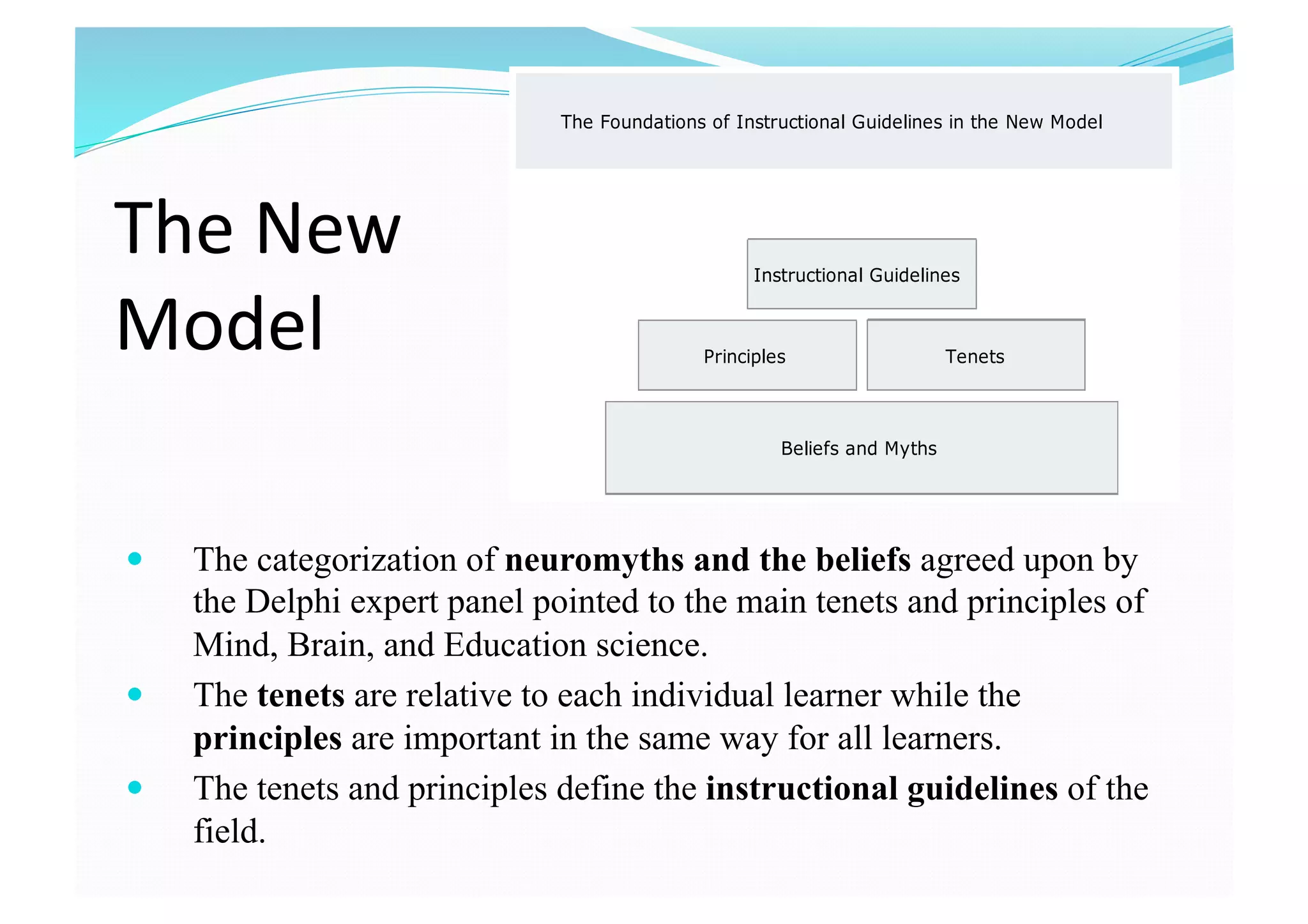

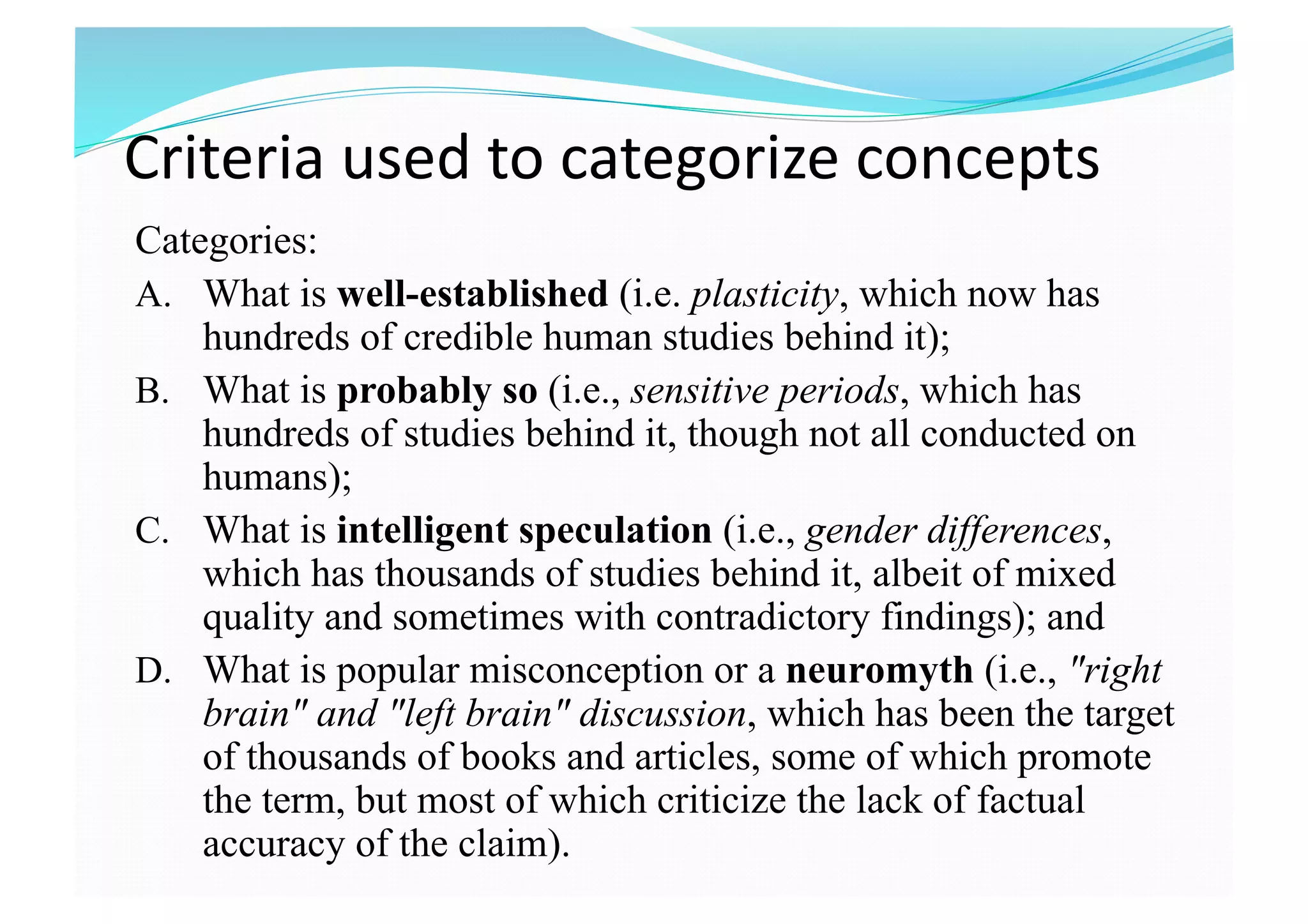

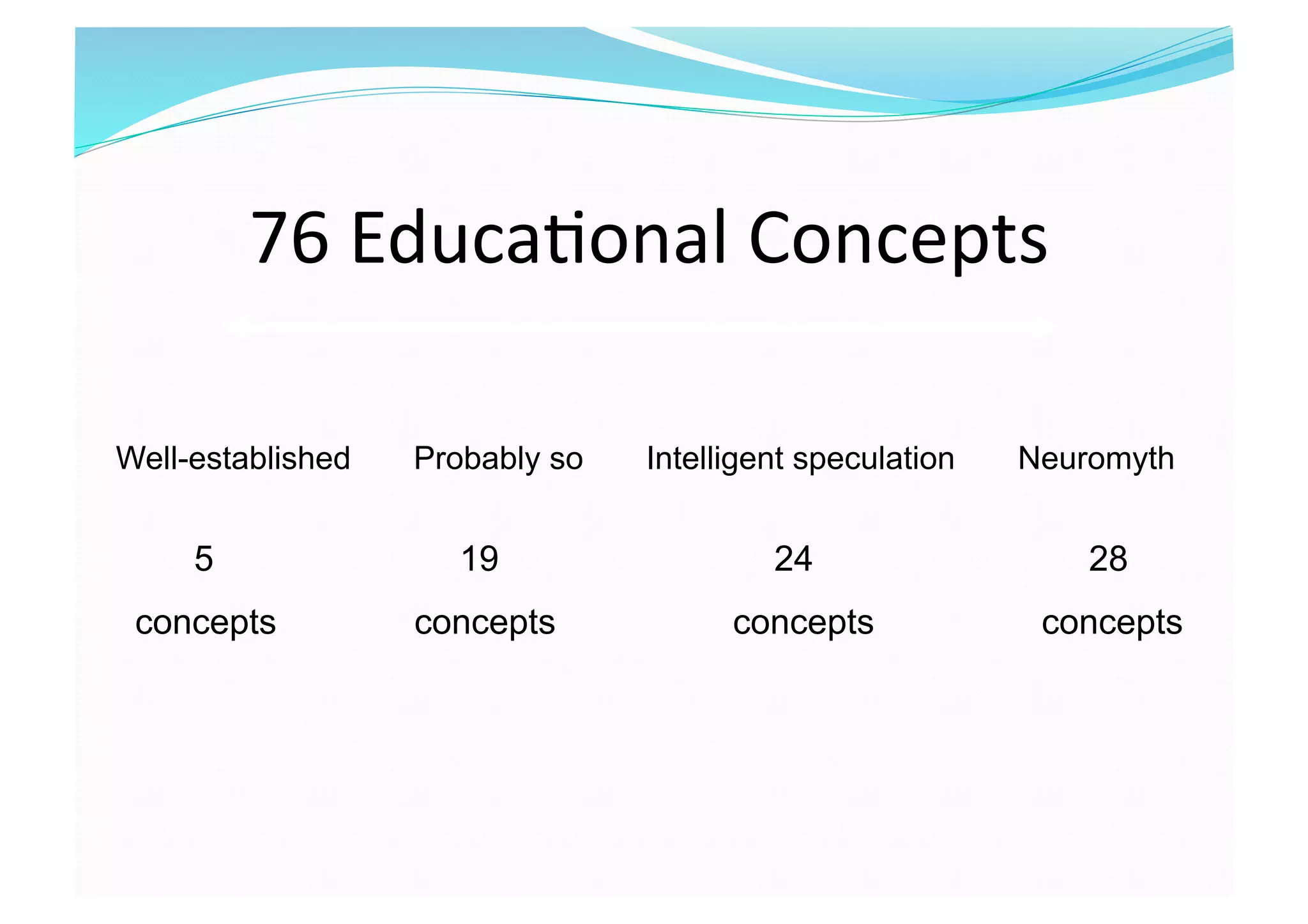

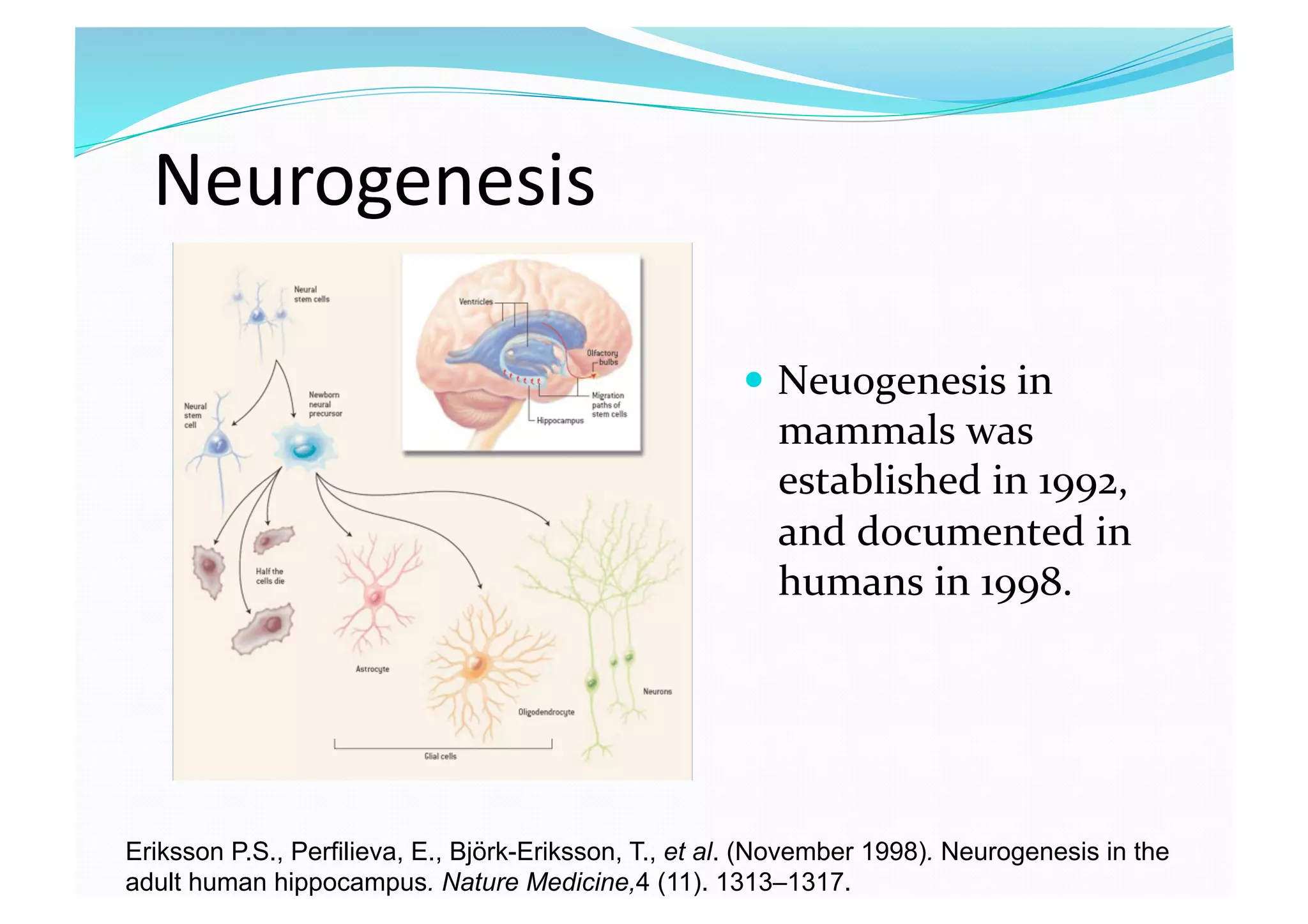

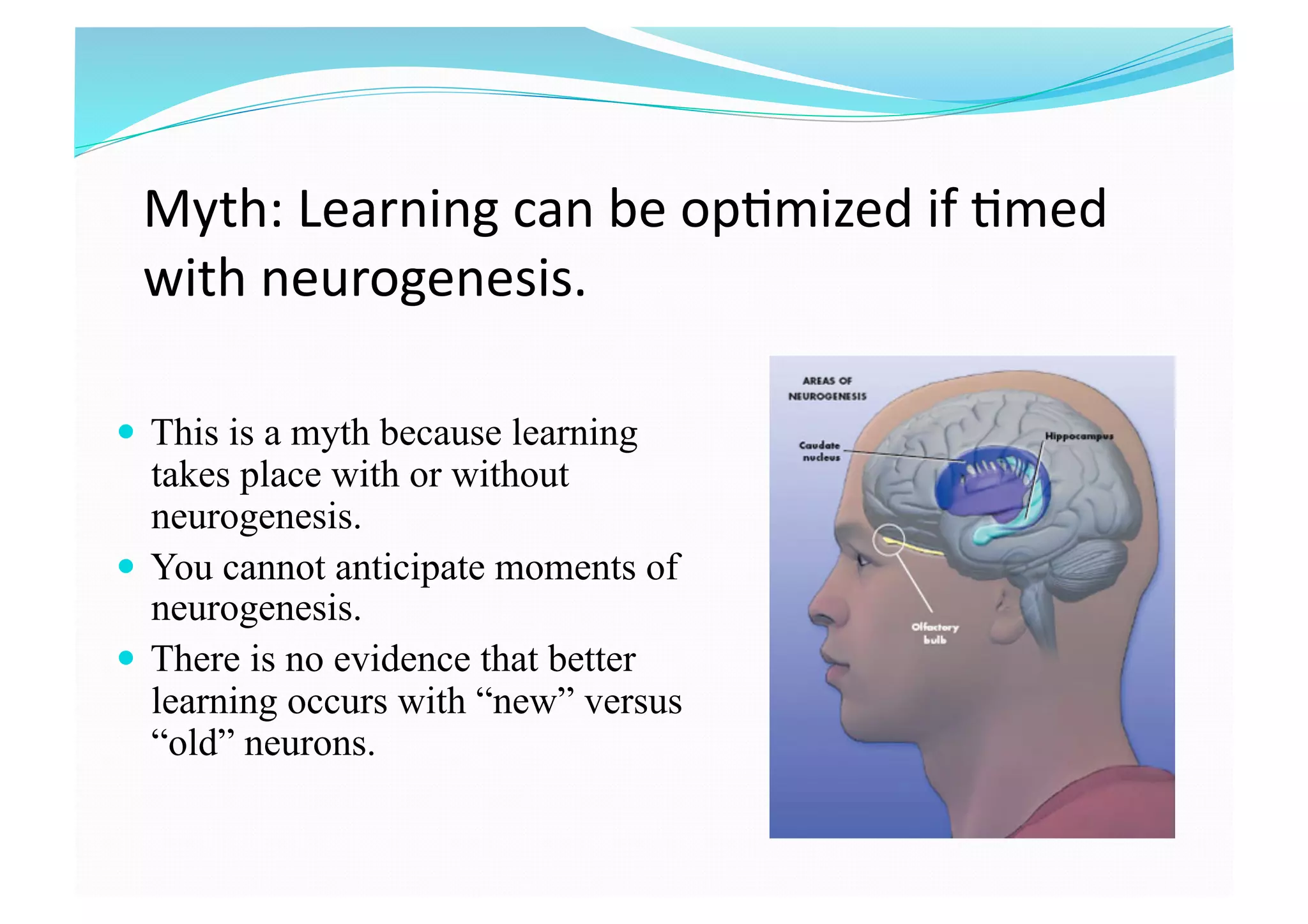

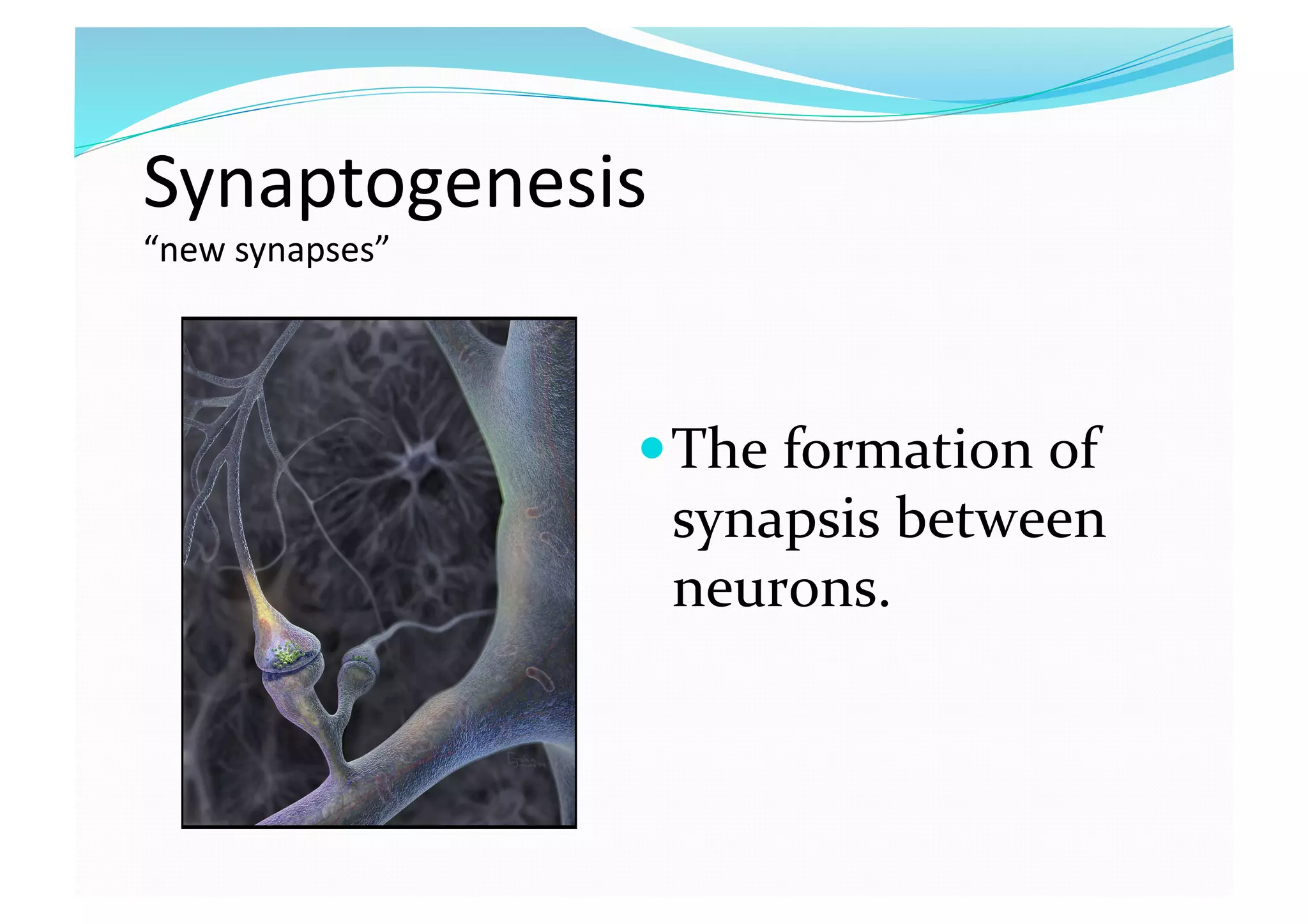

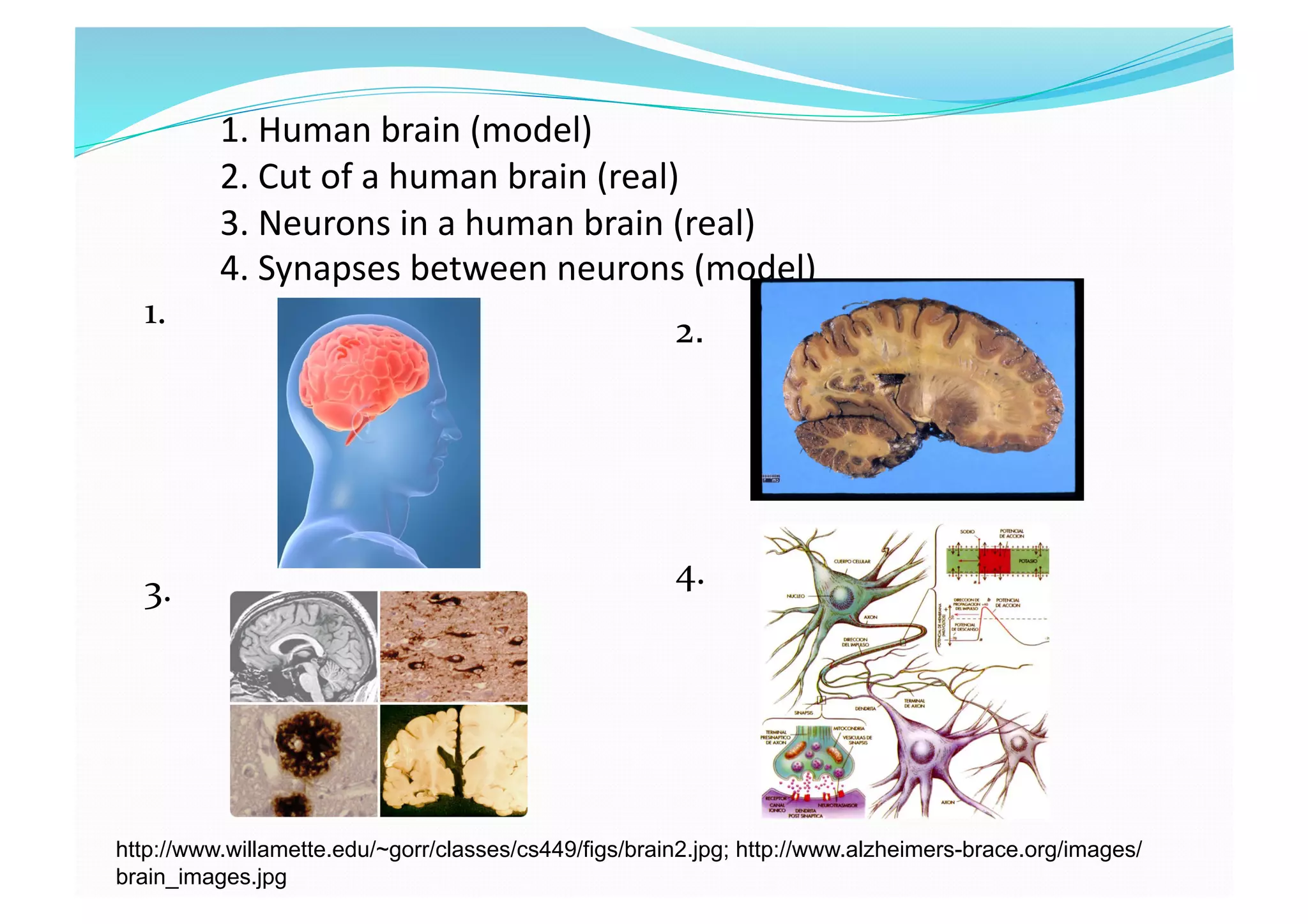

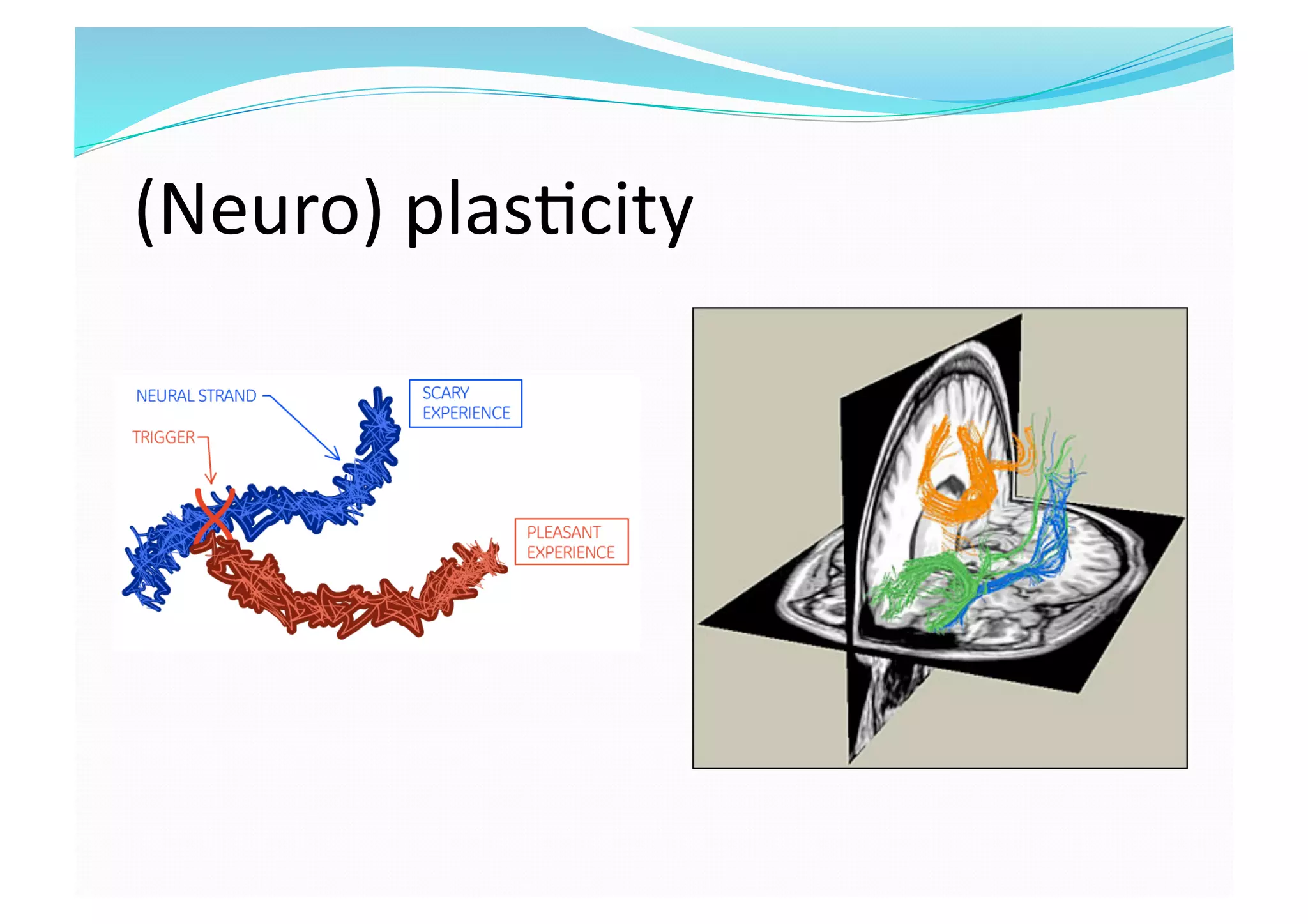

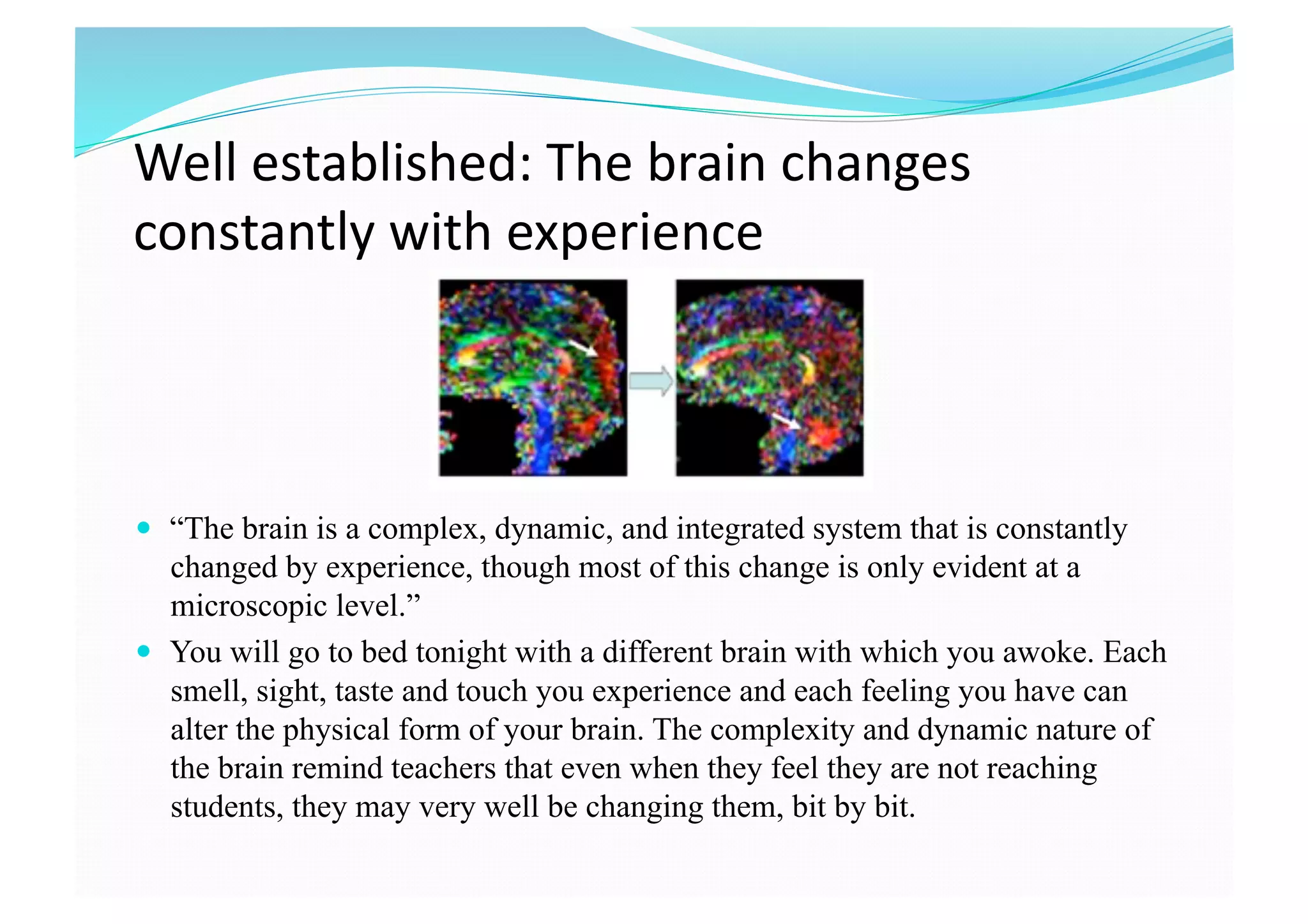

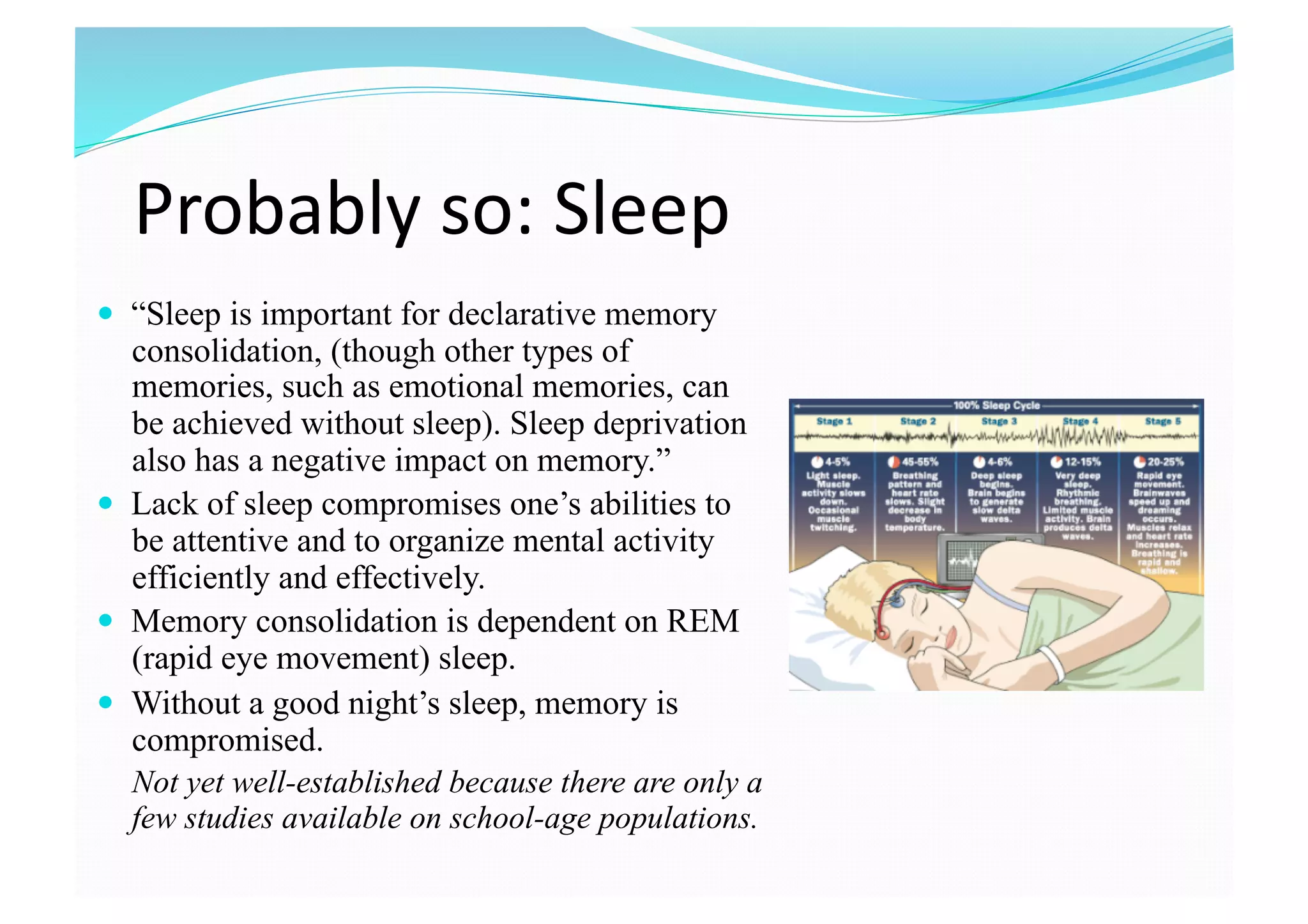

There has been an explosion of research in neuroscience that is changing perspectives on learning and education. While standards exist separately in neuroscience, psychology, and pedagogy, until recently there were no agreed upon standards at their intersection, known as Mind, Brain, and Education science. The document discusses the development of a new model for Mind, Brain, and Education science based on a literature review and input from a panel of experts across relevant fields. Key aspects of the model include categorizing educational concepts based on levels of evidence and establishing principles and guidelines for instruction. Definitions of neurogenesis and neuroplasticity are also provided.