The document discusses thyroid hormones, their biosynthesis, regulation, actions, and peripheral conversion. Some key points:

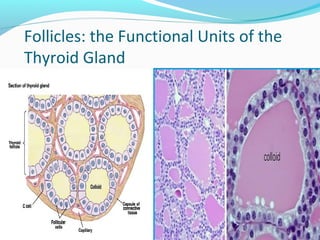

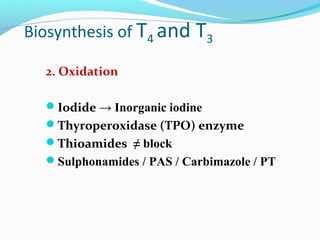

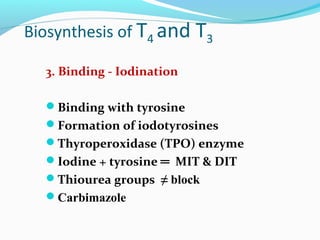

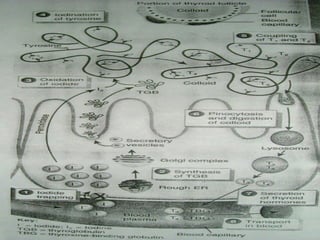

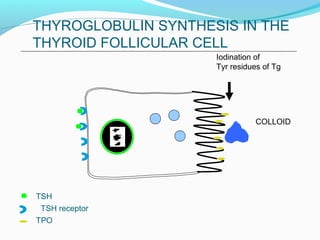

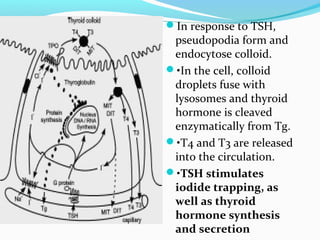

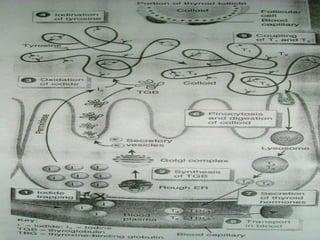

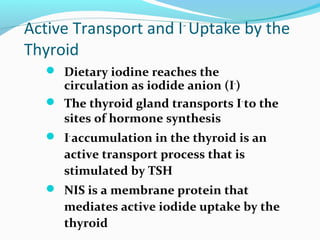

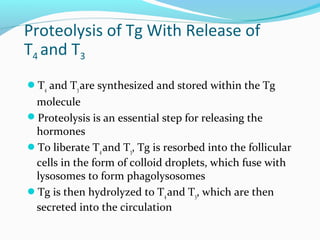

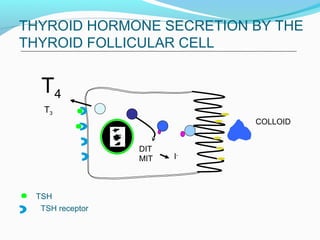

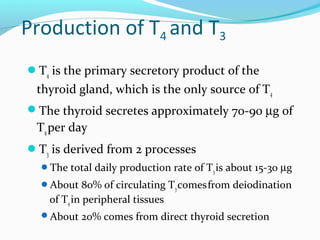

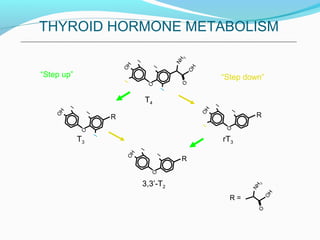

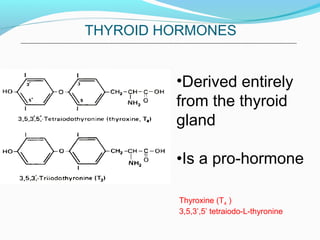

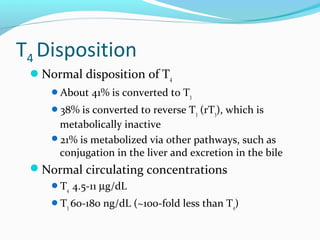

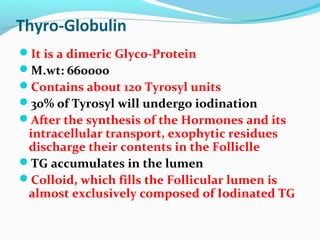

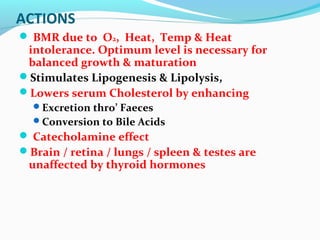

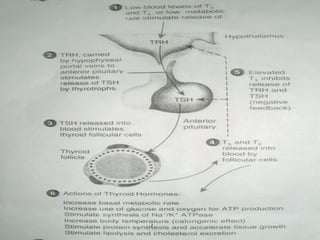

- Thyroid hormones T4 and T3 are synthesized in thyroid follicles from iodine and tyrosine. T4 is the main secretory product while T3 is the biologically active form.

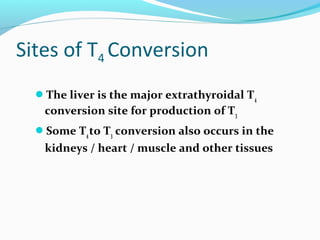

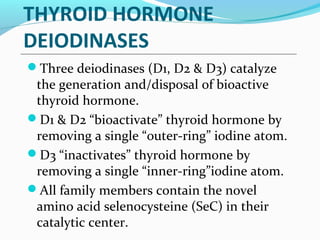

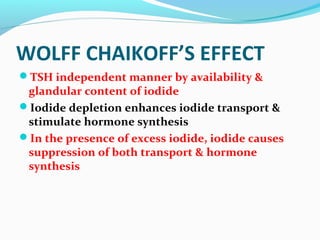

- TSH stimulates thyroid hormone synthesis and secretion. T4 is converted to T3 in tissues by deiodinase enzymes.

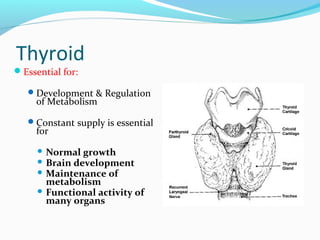

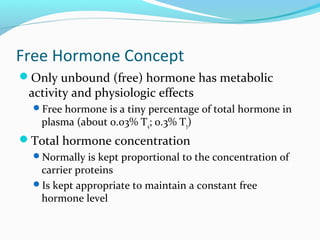

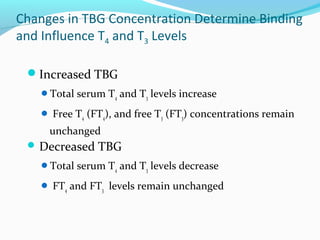

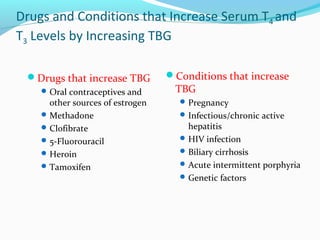

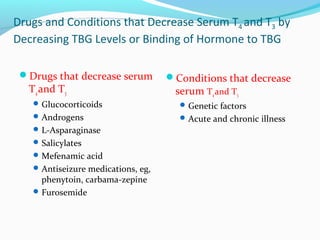

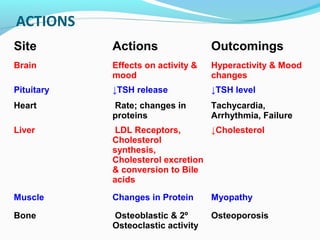

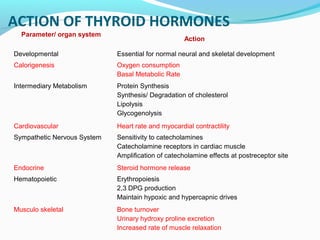

- Thyroid hormones are transported bound to carrier proteins and the free forms enter cells to increase metabolism.

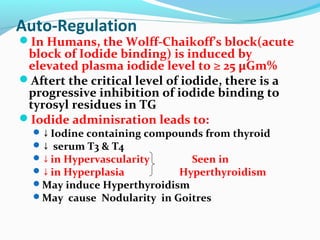

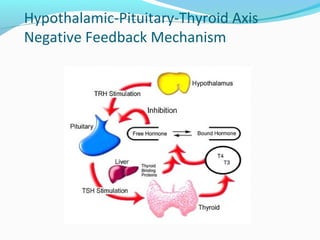

- Thyroid hormone levels are regulated by a negative feedback loop involving the hypothalamus, pituitary and thyroid gland.