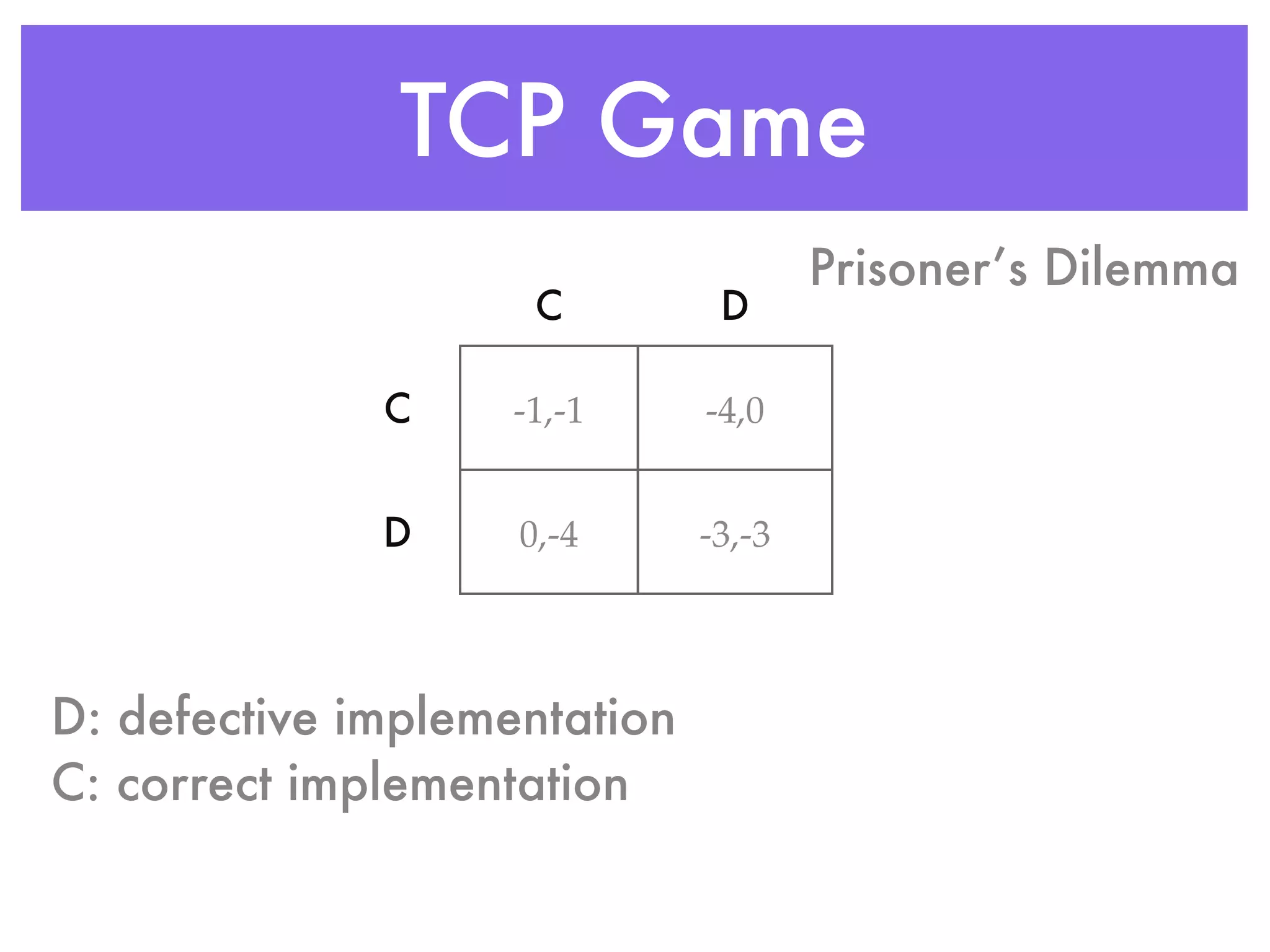

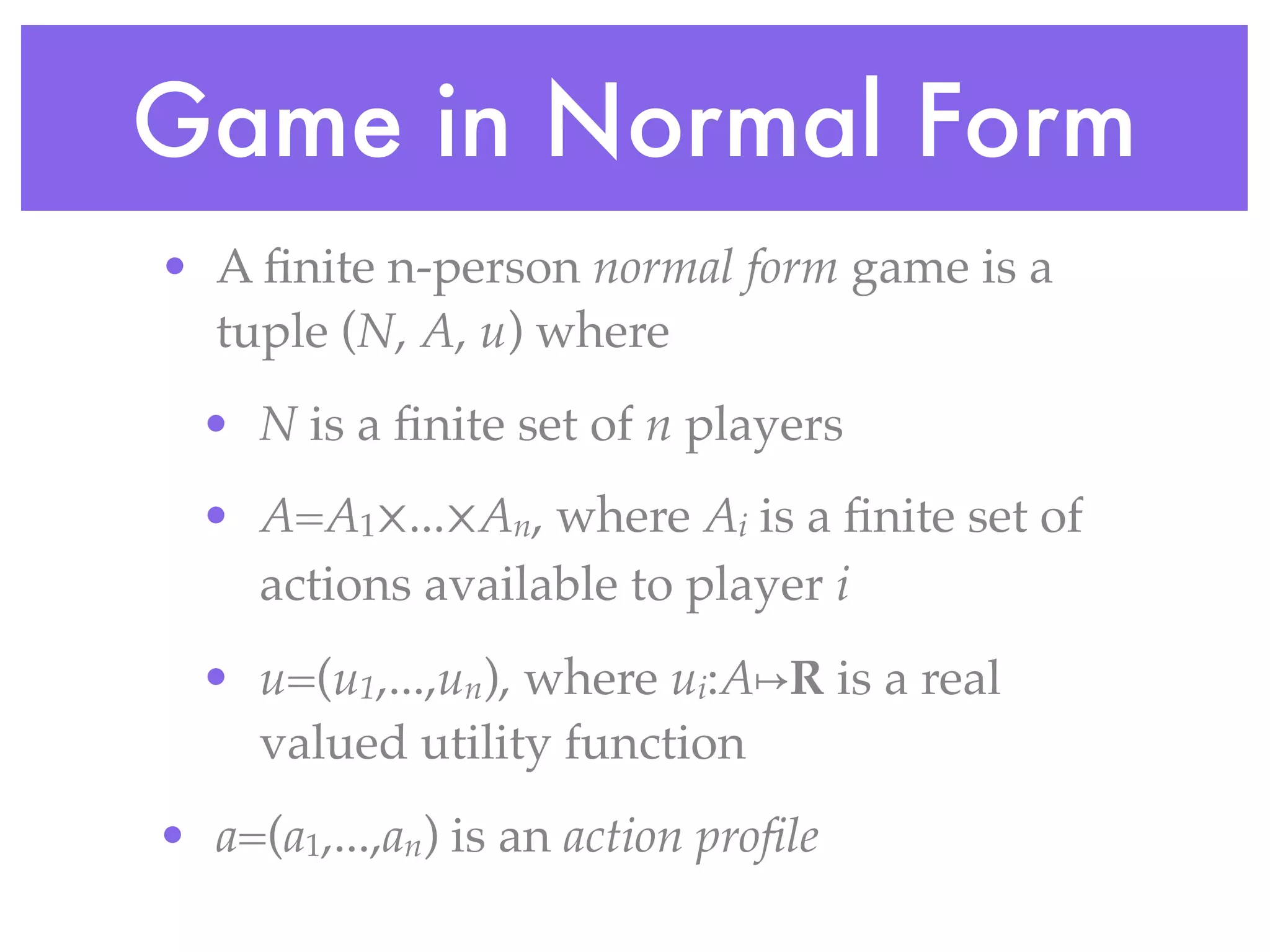

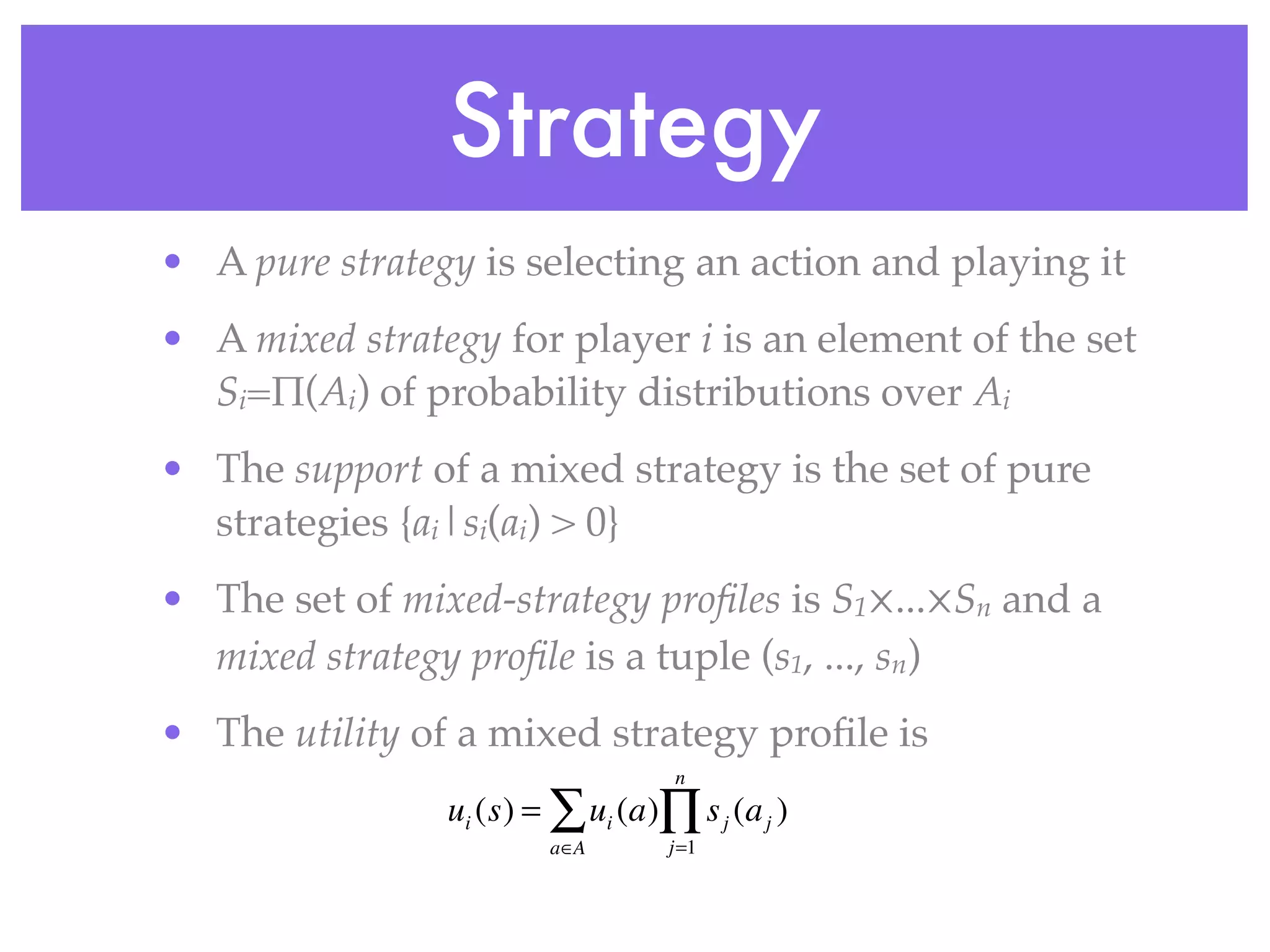

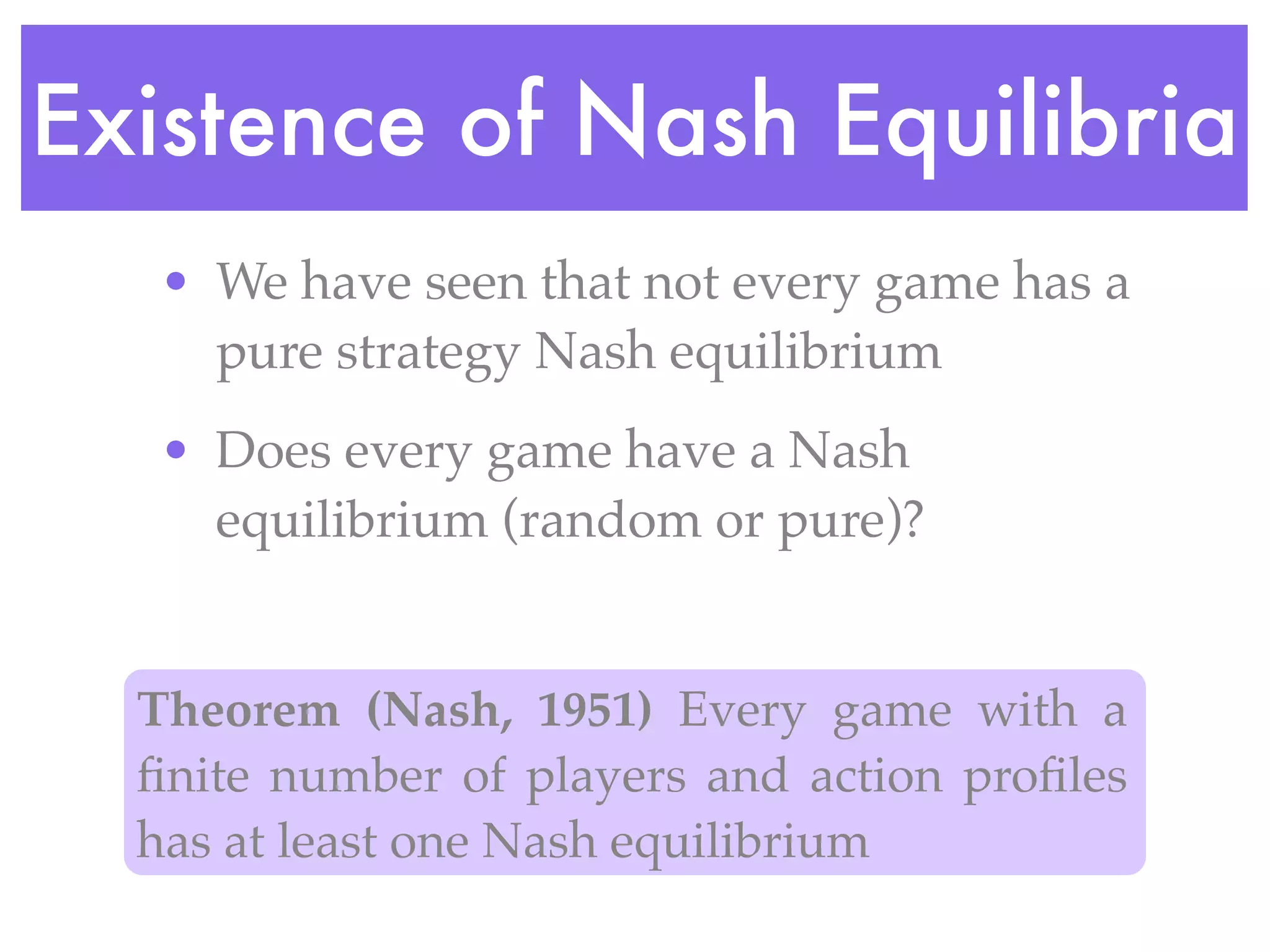

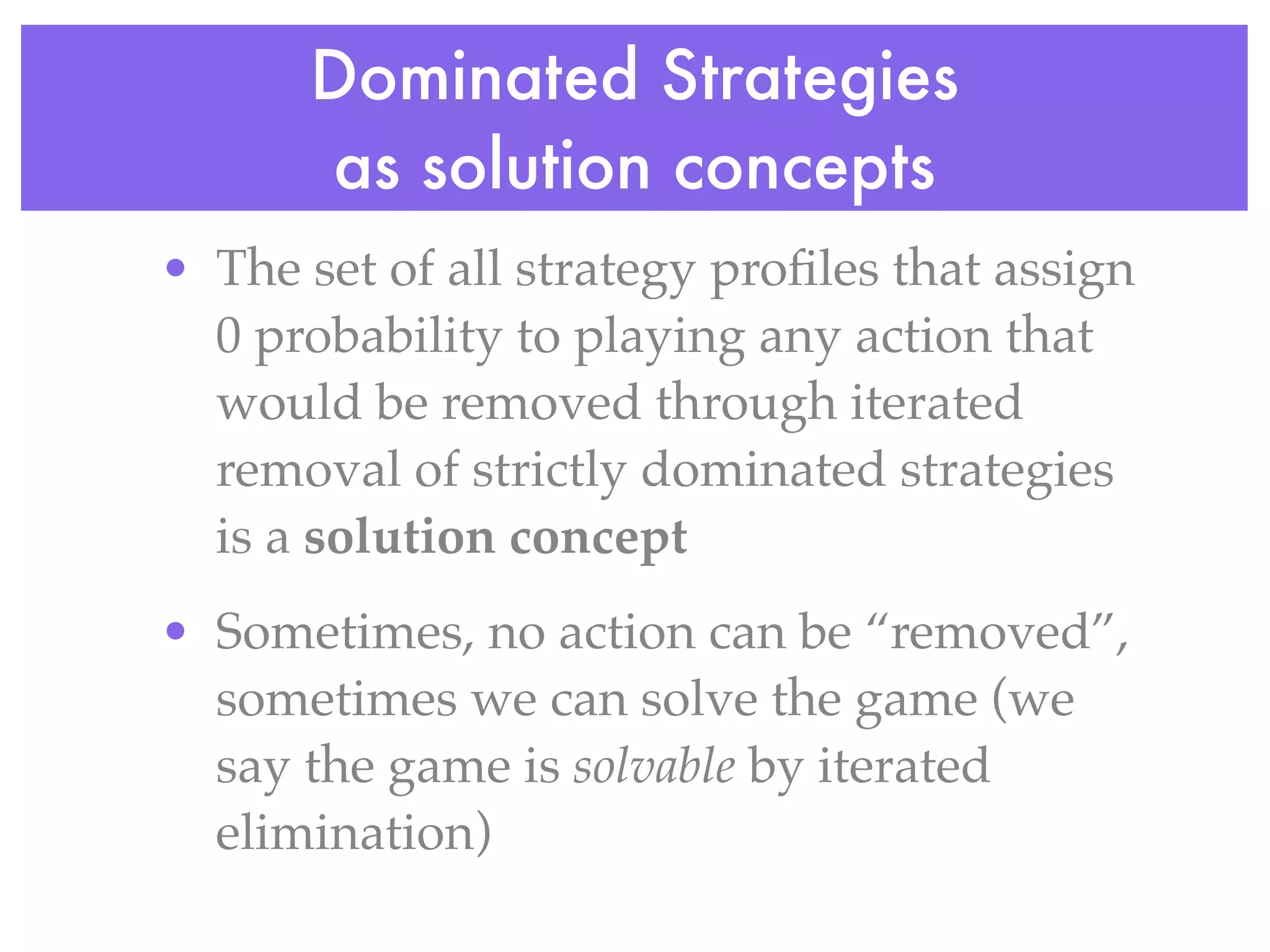

Game theory is the study of mathematical models of conflict and cooperation between rational decision-makers. It analyzes strategic decision-making through modeling games with several players under conditions of both cooperation and conflict. Game theory looks at solution concepts such as Nash equilibria, which are strategy profiles where each player's strategy is a best response to the other players' strategies. It is used to understand outcomes in strategic interactions in economics, political science, and other fields.

![Outcomes

• Let O be a finite set of outcomes

• A lottery is a probability distribution

over O l = [ p1 : o1 ,…, pk : ok ]

oi ∈O pi ∈[0,1]

k

∑p i =1

i=1

• We assume agents can rank outcomes

and lotteries with a utility function](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/game-theory-120604121557-phpapp01/75/Game-theory-4-2048.jpg)

![Maxmin vs. Minmax Regret

L R

regret(T ,[R])= 1− 1+ =

regret(B,[R]) = 1− 1 = 0

regret(T ,[L]) = 100 − 100 = 0 T 100, a 1-!, b

regret(B,[L]) = 100 − 2 = 98

max regret(T )= max{,0} = B 2, c 1, d

max regret(B) = max{98,0} = 98

P1 Maxmin is B (why?), his

Minimax Regret strategy is T](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/game-theory-120604121557-phpapp01/75/Game-theory-35-2048.jpg)