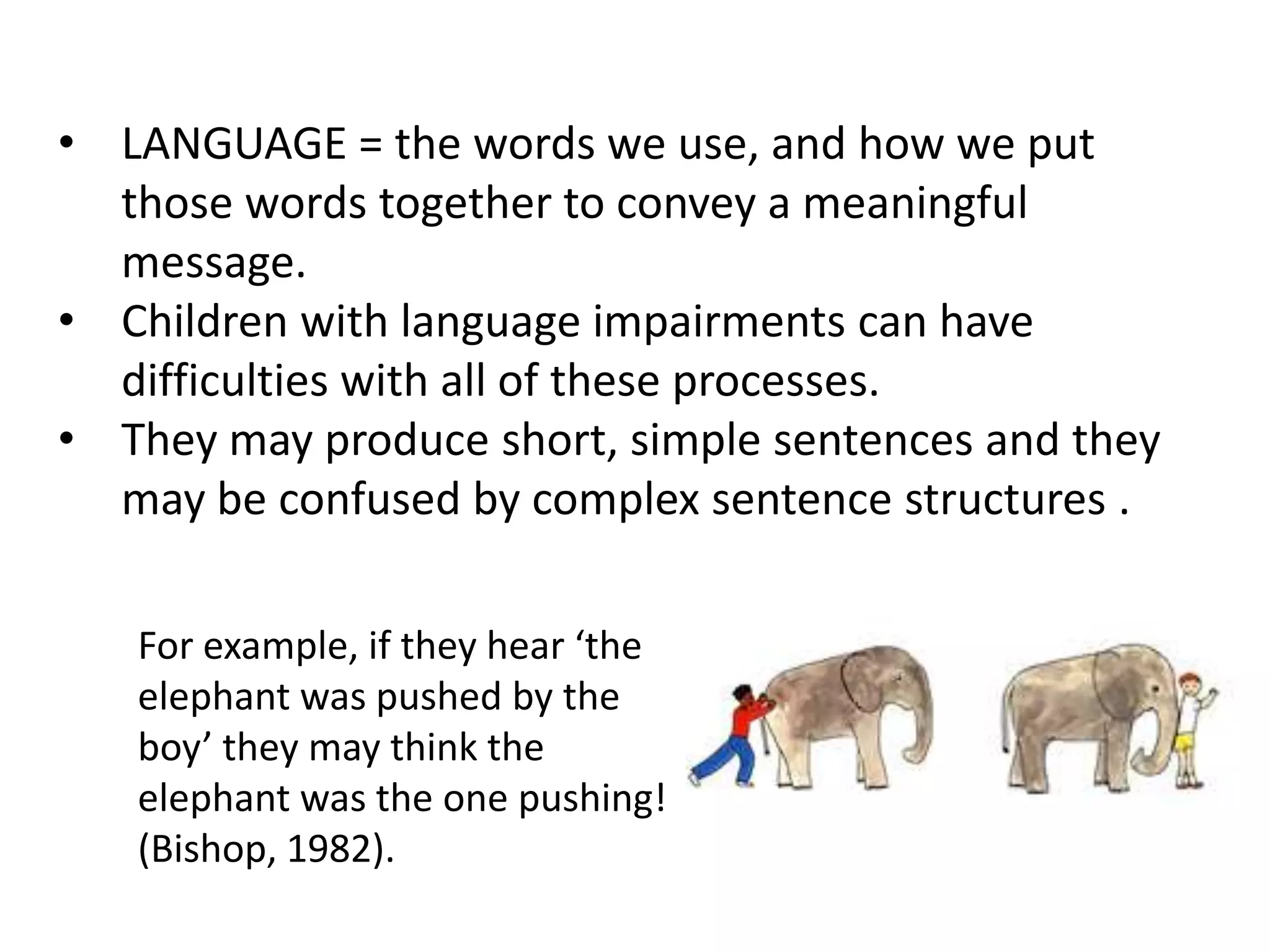

The document discusses speech, language, and communication needs (SLCN) in school-aged children in the UK, highlighting that they can exhibit diverse difficulties. It distinguishes between speech production, language comprehension, and communication skills, emphasizing that while many children with speech difficulties are easily identified, those with only language impairments may be overlooked. Finally, it notes that speech, language, and communication can be interrelated yet separate, illustrating the complexities involved in diagnosing and supporting affected children.