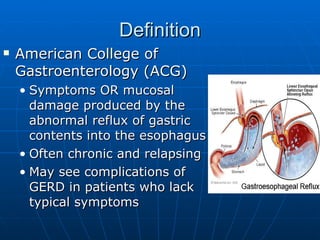

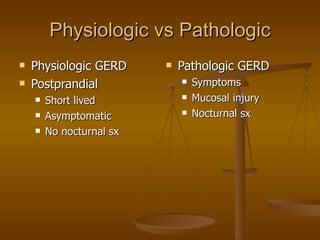

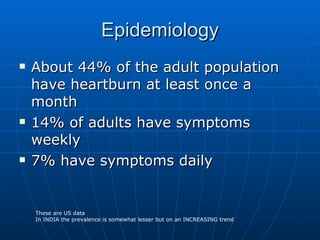

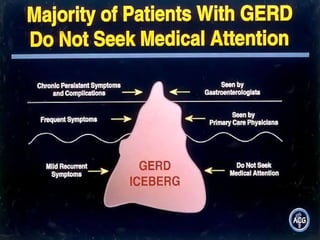

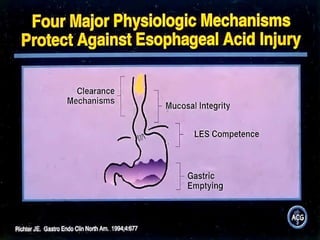

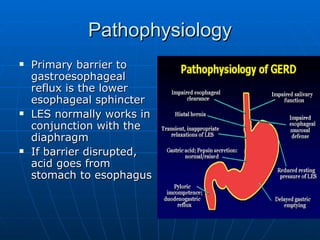

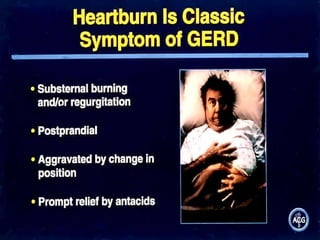

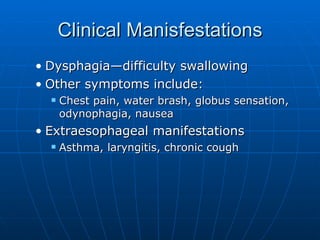

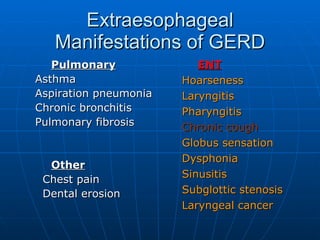

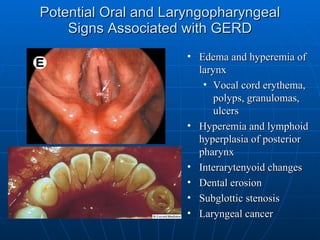

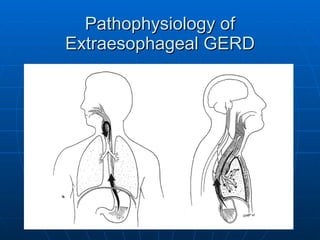

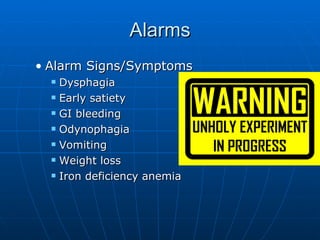

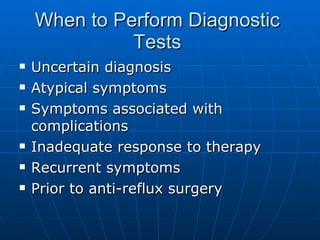

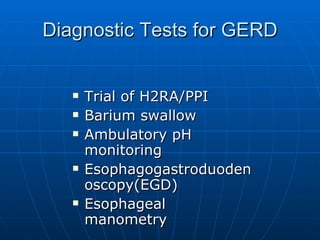

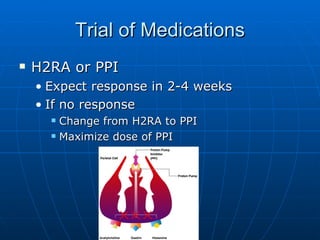

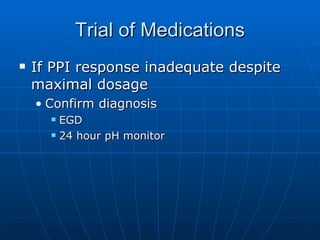

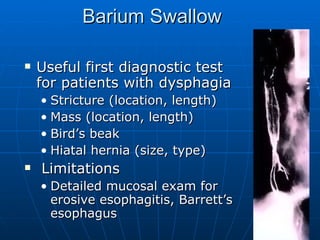

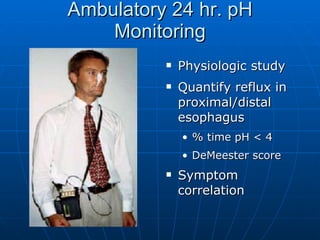

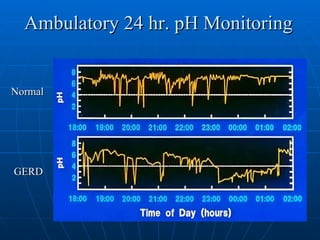

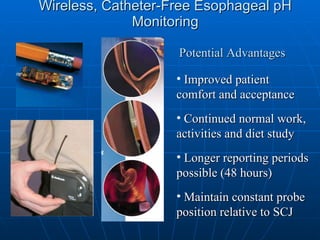

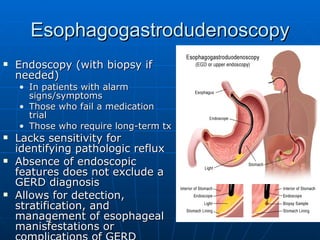

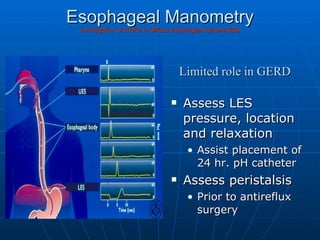

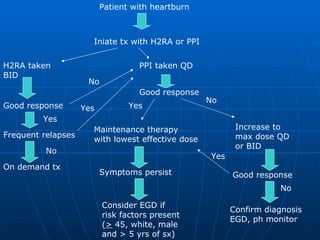

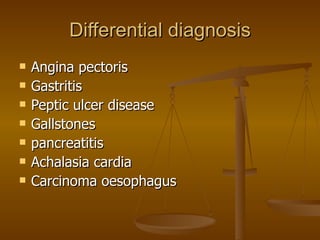

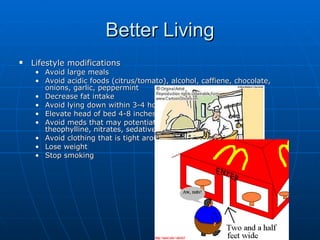

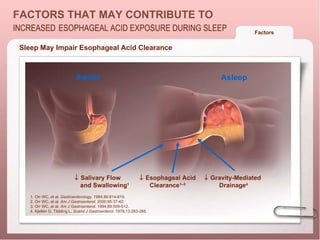

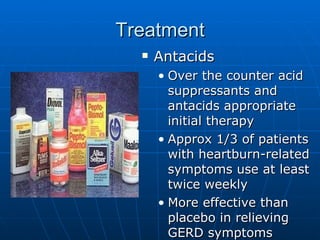

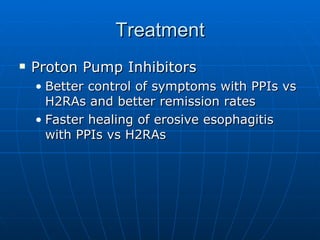

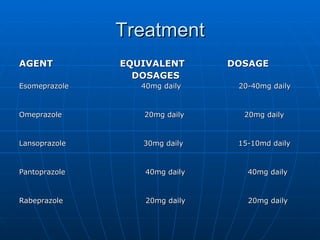

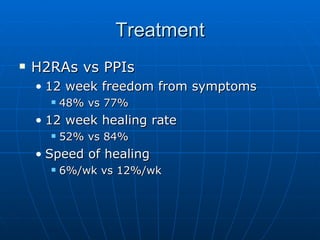

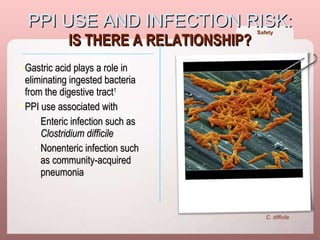

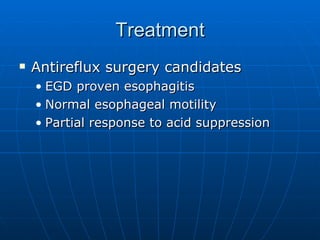

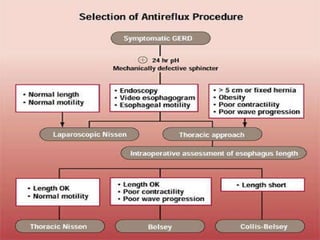

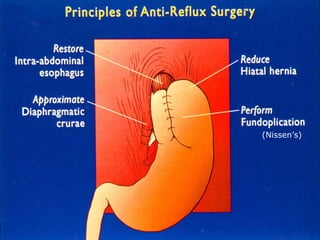

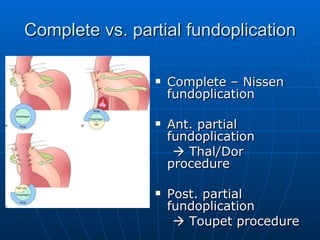

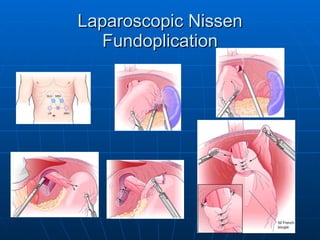

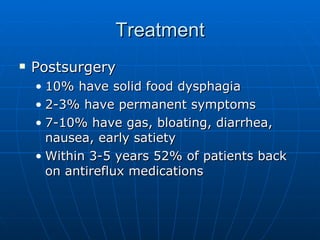

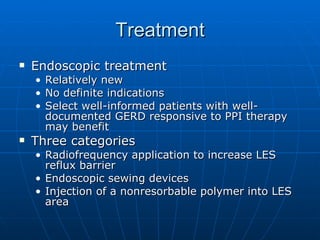

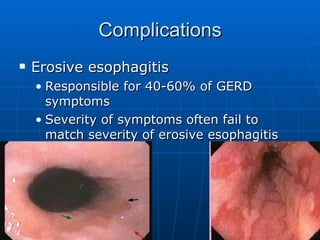

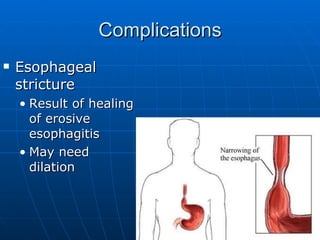

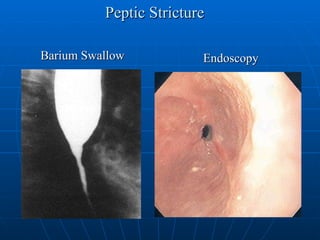

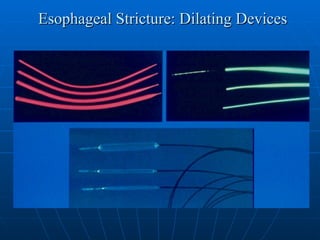

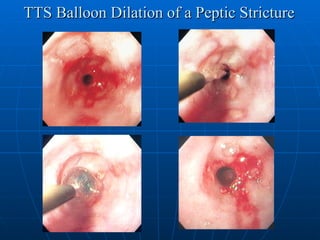

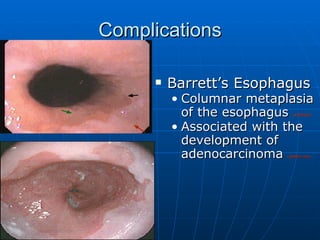

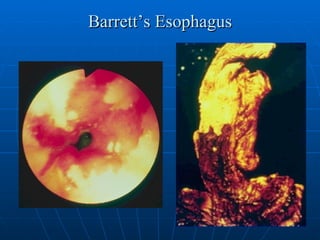

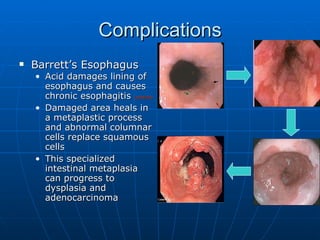

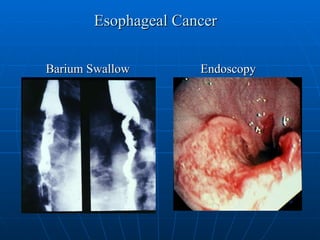

GERD is a common condition where stomach acid refluxes into the esophagus, potentially causing symptoms like heartburn and damage to the esophagus. About 44% of adults experience heartburn monthly, with risk factors including obesity, smoking, and hiatal hernia. Diagnosis involves assessing symptoms, and testing may include pH monitoring or endoscopy. Treatment focuses on lifestyle changes and medications like PPIs to reduce acid production, while complications can include esophagitis, strictures, and Barrett's esophagus, a precursor to esophageal cancer. Surgery is an option for severe cases that do not respond to medical management.