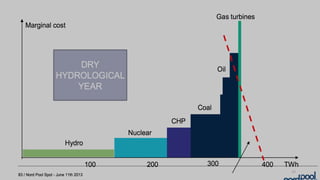

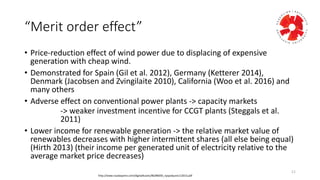

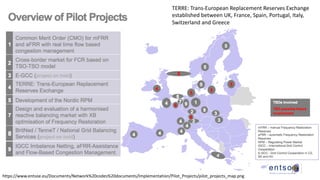

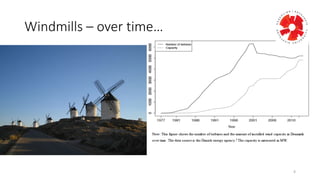

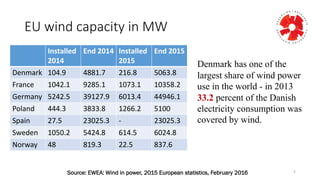

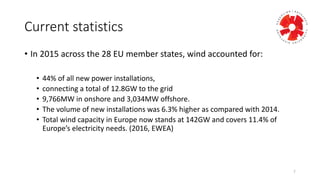

The document discusses the challenges and statistics of wind energy in Europe, outlining the increasing capacity and share of wind power in electricity generation, particularly in Denmark. It highlights issues such as price volatility, wear and tear on conventional power plants, and the integration of renewable sources into the energy market. The document also references the need for cross-border balancing markets to manage the intermittent nature of wind generation and improve overall system efficiency.

![Wind

energy

– challenges

• “Merit

order

effect”

• Increased

price

volatility

• Increased

wear

and

tear

• Balancing

issues

• Towards

the

European

Balancing

Market

• “[…]

a

cross

border

balancing

market

will

help

to

counteract

the

effects

of

intermittent

generation

and

allow

the

integration

of

more

renewable

energy

sources”.

9](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/04ewawindchallengessiteenergyday-161014101104/85/Wind-energy-challenges-9-320.jpg)